Main Body

Module 6 Impressionism & Post-Impressionism

(Monet, Degas, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne)

Impressionism

Read:”Impressionism: Art and Modernity” by Margaret Samu via Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 2004).

A Beginner’s Guide to Impressionism

Apart from the salon

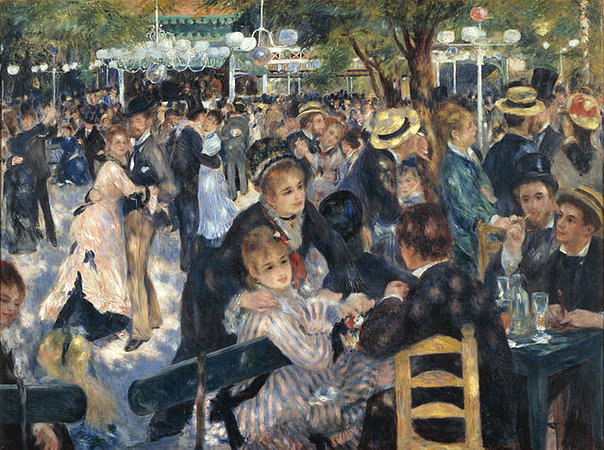

The group of artists who became known as the Impressionists did something ground-breaking in addition to painting their sketchy, light-filled canvases: they established their own exhibition. This may not seem like much in an era like ours, when art galleries are everywhere in major cities, but in Paris at this time, there was one official, state-sponsored exhibition—called the Salon—and very few art galleries devoted to the work of living artists. For most of the nineteenth century then, the Salon was the only way to exhibit your work (and therefore the only way to establish your reptutation and make a living as an artist). The works exhibited at the Salon were chosen by a jury—which could often be quite arbitrary. The artists we know today as Impressionists—Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley (and several others)—could not afford to wait for France to accept their work. They all had experienced rejection by the Salon jury in recent years and felt that waiting an entire year between exhibitions wastoo long. They needed to show their work and they wanted to sell it.

The artists pooled their money, rented a studio that belonged to the photographer Nadar, and set a date for their first collective exhibition. They called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Printmakers and their first show opened at about the same time as the annual Salon in May 1874. The Impressionists held eight exhibitions from 1874 through 1886.

The impressionists regarded Manet as their inspiration and leader in their spirit of revolution, but Manet had no desire to join their cooperative venture into independent exhibitions. Manet had set up his own pavilion during the 1867 World’s Fair, but he was not interested in giving up on the Salon jury. He wanted Paris to come to him and accept him—even if he had to endure their ridicule in the process.

Lack of finish

Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Sisley had met through classes. Berthe Morisot was a friend of both Degas and Manet (she would marry Édouard Manet’s brother Eugène by the end of 1874). She had been accepted to the Salon, but her work had become more experimental since then. Degas invited Morisot to join their risky effort. The first exhibition did not repay the artists monetarily but it did draw the critics, some of whom decided their art was abominable. What they saw wasn’t finished in their eyes; these were mere “impressions.” This was not a compliment.

The paintings of Neoclassical and Romantic artists had a finished appearance. The Impressionists’ completed works looked like sketches, fast and preliminary “impressions” that artists would dash off to preserve an idea of what to paint more carefully at a later date. Normally, an artist’s “impressions” were not meant to be sold, but were meant to be aids for the memory—to take these ideas back to the studio for the masterpiece on canvas. The critics thought it was absurd to sell paintings that looked like slap-dash impressions and to present these paintings as finished works.

Landscape and contemporary life

Courbet, Manet and the Impressionists also challenged the Academy’s category codes. The Academy deemed that only “history painting” was great painting. These young Realists and Impressionists questioned the long establiished hierarchy of subject matter. They believed that landscapes and genres scenes (scenes of contemporary life) were worthy and important.

Light and color

In their landscapes and genre scenes, the Impressionist tried to arrest a particular moment in time by pinpointing specific atmospheric conditions—light flickering on water, moving clouds, a burst of rain. Their technique tried to capture what they saw. They painted small commas of pure color one next to another. When viewer stood at a reasonable distance their eyes would see a mix of individual marks; colors that had blended optically. This method created more vibrant colors than colors mixed as physical paint on a palette.

An important aspect of the Impressionist painting was the appearance of quickly shifting light on the surface of forms and the representation changing atmospheric conditions. The Impressionists wanted to create an art that was modern by capturing the rapid pace of contemporary life and the fleeting conditions of light. They painted outdoors (en plein air) to capture the appearance of the light as it flickered and faded while they worked.

Reception

By the 1880s, the Impressionists accepted the name the critics gave them, though their reception in France did not improve quickly. Other artists, such as Mary Cassatt, recognized the value of the Impressionist movement and were invited to join. American and other non-French collectors purchased numerous works by the Impressionists. Today, a large share of Impressionist work remains outside French collections.

Edgar Degas “The Dance Class”

Claude Monet “The Argenteuil Bridge”

Speakers: Drs. Beth Harris and Steven Zucker

Please note that there is significant background chatter in this video. The Musée d’Orsay is happily a very busy museum and this painting is hung in a relatively small room.

Post-Impressionism

Source[2]

Move from Naturalism

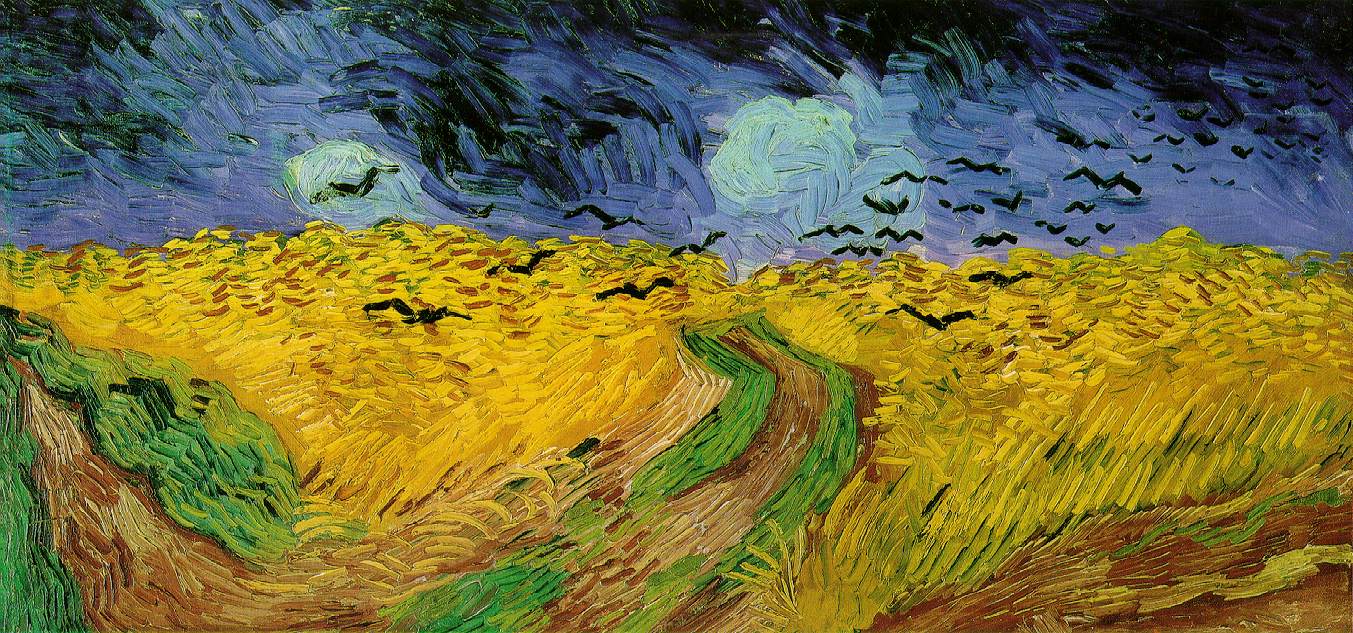

Post-Impression refers to a genre of painting that rejected the naturalism of Impressionism, in favor of using color and form in more expressive manners. The term “Post-Impressionism” was coined by the British artist and art critic Roger Fry in 1910 to describe the development of French art since Manet. Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations. For example, they continued using vivid colors, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, but they were also more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort forms for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary colors in their compositions.

Significant Artists of Post-Impressionism

Post-Impressionism developed from Impressionism. From the 1880s onward, several artists, including Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, envisioned different precepts for the use of color, pattern, form, and line, deriving these new directions from the Impressionist example. These artists were slightly younger than the Impressionists, and their work contemporaneously became known as Post-Impressionism. Some of the original Impressionist artists also ventured into this new territory. Camille Pissarro briefly painted in a pointillist manner, and even Monet abandoned strict plein air painting. Paul Cézanne, who participated in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions, developed a highly individual vision emphasizing pictorial structure; he is most often called a post-Impressionist. Although these cases illustrate the difficulty of assigning labels, the work of the original Impressionist painters may, by definition, be categorized as Impressionism.

A Diverse Search for Direction

The Post-Impressionists were dissatisfied with the triviality of subject matter and the loss of structure in Impressionist paintings, although they did not agree on the way forward. Georges Seurat and his followers, for instance, concerned themselves with Pointillism, the systematic use of tiny dots of colour . Paul Cézanne set out to restore a sense of order and structure to painting by reducing objects to their basic shapes while retaining the bright fresh colours of Impressionism. Vincent van Gogh used vibrant colors and swirling brush strokes to convey his feelings and his state of mind . Hence, although they were often exhibited together, Post-Impressionist artists were not in agreement concerning a cohesive movement, and younger painters in the early twentieth century worked in geographically disparate regions and in various stylistic categories, such as Fauvism and Cubism.

Post-Impressionism

Vincent van Gogh “The Bedroom”

Paul Gauguin “Vision After the Sermon”

Cezanne “Still Life with Plaster Cupid”

- Gersh-Nesic, B. "A Beginner's Guide to Impressionism." Smarthistory/KhanAcademy. CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Post-Impressionism.” Boundless Art History. 21 July 2015. CC-BY-SA 3.0 ↵