Chapter 7: Individuals in Organizations

7.1 Communication Styles

Cheryl Hamilton

Strong interpersonal relationships are not only the heart of a successful organization but they are also the foundation of our own business successes. To make relationships work, we need to understand our communication styles. Do you know yours? It is important because your communication style(s) affect your relationships with bosses, coworkers, teams, and customers. Each of us has a distinct communication style or styles that we feel the most comfortable using when things are going well and a different style or styles that we use under pressure or stress. Have you ever noticed that you behave differently when under stress or during a conflict? Many professions and businesses also seem to have preferred communication styles. In this section, we will look at four styles that managers, employees, and customers typically use when communicating and relating with each other: the private, dominant, sociable, and open styles. Few people are ever completely one style. Although a person may have some characteristics of all four styles, most people have one or sometimes two central styles they typically use. None of these styles is totally good or totally bad: each style has its “best” and “worst” side. Note that these four styles are a composite of several different style approaches as listed in in the footnote[1] and do not mirror any of them exactly. We have attempted to alter any criticisms or weaknesses of these approaches and have developed two Polishing Your Career Skills surveys both located near the end of this chapter to help you determine your main styles used as an employee and as a manager.

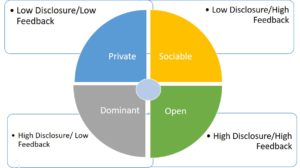

Waldherr and Muck (2011) conducted a literature review of research on communication styles and concluded that two reliable dimensions stand out in the research so far—high and low assertiveness and high and low responsiveness. People who are high in assertiveness are more likely to disclose information and feelings, while people who are high in responsiveness are more likely to seek and reply to the feedback of others. The disclosure/assertiveness and the feedback/responsiveness

dimensions have been combined in this edition as you can see in diagram below.

To communicate more successfully and establish more meaningful working relationships, employees need to (a) understand each style including its strengths and weaknesses, (b) learn how to communicate effectively with people using styles different from their own (whether they are supervisors, coworkers, or customers), and (c) determine their personal communication styles. Let’s start with understanding each style.

Communication Styles: What Are They?

Please realize that this classification system of four styles is not intended to serve as a method for stereotyping people but as a practical way of understanding your own and others’ frames of reference. As you read remember that the descriptions of these styles are not perfect or even complete; rather, they describe tendencies. As such, we hope you will find them as helpful in your daily business and professional careers as our many students and business seminar participants have over the years.

The Private Style

If you had the choice of a job in a room with five or six other people whom you would work with each day or a job in a room by yourself, working with a machine that only one person could operate at a time, which would you choose? If you selected to work alone, you probably have strong private tendencies. Private-style communicators simply feel more comfortable working with things than with people—does this seem like you? For example, a private-style employee might do well working at restocking items or finding glitches in a s software program but be inefficient when handling customers at a complaint window or working in a group. A private-style manager may enjoy inventory control, ordering

supplies, and detail work, but may also be less successful dealing with employees and employee problems. The private-style communicators seek little feedback, which makes them low on the responsiveness continuum, and disclose little information, which also makes them low on the assertiveness continuum. In other words, they are noncommunicators, who not only feel uncomfortable around people, they may actually fear them.

Because private-style people find it difficult to communicate their expectations to others, they are often disappointed by and disappointing to those around them. For example, the boss who expects private-style employees to actively participate in group meetings and decision making will be disappointed. Asking their opinion in meetings does not make it easier for them to participate; instead, it increases their anxiety. Private-style customers are often disappointed by salespeople (they really want to be led by the hand but are afraid to ask). If the product or service recommended by the salesperson turns out to be poor, rarely will private-style customers openly complain. Instead, they may change stores without letting the store or letting the salesperson know why.

Private-style people spend much of their energy in seeking safety to keep from looking like fools, being blamed for something, or even losing their jobs. They try to avoid conflict and avoid making decisions. When decisions have to be made, they use safe procedures such as “going by the book,” following tradition, and treating everyone alike. Actions taken by private-style managers in an attempt to remain safe include treating all employees the same regardless of their performance, giving only brief, superficial employee appraisals (and then only when absolutely necessary), and never initiating upward communication.

Private-style people can be quite productive as long as only minimal interaction

with others is required. However, because of their communication anxiety, relationships with private-style people are difficult—especially in the work environment. As a result, creative employees and employees who need guidance often become frustrated with the private-style manager. On the other hand, other private-style employees and highly trained and motivated employees who like to make their own decisions appreciate the private-style manager, who stays out of their way and concentrates on computers, equipment, and other “things.”

To summarize, the private style is most successful when little interpersonal interaction is required for the job, when going by the book is the preferred company stance, when subordinates are professionals who need little supervision, and when others in the department are private or prefer things to people. The private style is less successful when the job requires a high level of interpersonal interaction; when the organization is in a high-risk profession with

creative, high-strung individuals; when subordinates need or want guidance; and when the profession or business is productivity-oriented.

The Dominant Style

If you are looking for someone you can depend on to get the job done, someone to train a group of overconfident new hires, someone with the self assurance to troubleshoot a problem department, or someone who can command authority in a crisis, you couldn’t do better than to hire a dominant-style communicator. Whereas private-style communicators would experience disabling anxiety in these situations, dominant-style communicators thrive in situations in which they can demonstrate their expertise and experience—does this sound like you?

The dominant-style communicators tend to fall on the low-feedback/responsiveness and high-disclosure/assertiveness ends of the two continuums, which causes others to view them as authoritarian. As with private-style people, dominant-style communicators seldom ask for feedback, and yet they are the opposite of private communicators in several ways. Instead of having a low self-image, dominant-style communicators tend to be very confident (even overly confident) and are not afraid to express their views, expectations, or needs. People know where they stand with a dominant-style communicator. Dominant communicators don’t ask for feedback from others because they don’t feel they need it; they already know what’s best. Instead of avoiding others, dominant-style communicators tend to overuse disclosure, telling others their opinions, how things should be done, and what others are doing wrong, even when their advice may not be wanted. For example, it’s very difficult for dominant-style managers to delegate responsibility. They want employees to do the work but to do it the way they themselves would do it. Private and dominant communicators also differ in the way they handle conflict. Instead of ignoring conflict, dominant communicators jump right in and solve the problem their way, using force if necessary. Often, dominant-style managers solve conflicts without asking for employee

agreement or input.

Actually, dominant-style communicators are often right when they say their ideas are better. They are usually experienced and very knowledgeable on the topic. But when people are not allowed to give feedback, to try things their way, or to make mistakes, they can’t develop their potential. Therefore, even though dominant-style managers are good trainers, they don’t allow their employees the freedom to develop to the point at which they can take over for the boss. When the manager is promoted or leaves, the organization usually discovers that there is no one ready to fill the position.

Dominant-style communicators are seen as very critical and demanding. For example, although dominant-style managers mention employee strengths in appraisal sessions, they spend the majority of the time on weaknesses. Their comments probably don’t include “face supportive” communication (Carson & Cupach, 2000)—comments and nonverbal gestures designed to show employee approval and give the employee some choices. In the same way, dominant-style employees (feeling that their ideas are better than those of their bosses) are argumentative and have problems gracefully receiving criticism or orders. Even dominant-style customers are very critical (often knowing more about a product than the salesperson) and are usually the first to tell their friends when they are unhappy with a particular organization.

If you have dominant-style tendencies, you have probably discovered that most people are not interested in the perfect way to do things. Most people want the job completed but are not impressed by all the hard work that “perfection” requires. If you often feel dismayed by the quality of others’ ideas and think to yourself, “If I want something done right, I’ve got to do it myself,” you are exhibiting dominant-style tendencies as are often found in the traditional organization. Occasionally, a person who appears to be dominant is really a very insecure, private-style person who notices that dominant communicators get more desired results (such as more job promotions) than private ones and decides to try the dominant style. Therefore, these people—we’ll call them neurotic dominant communicators—hide their insecurity behind an authoritarian mask. Instead of the constructive criticism given by a dominant manager, the neurotic dominant manager’s criticism is angry and includes unrealistic personal attacks. To hide the fact that they feel threatened by knowledgeable, hardworking employees, neurotic dominant managers find a minor employee weakness and blow it out of proportion—often in front of other employees. Therefore, don’t confuse the true dominant communicator with the neurotic dominant communicator. Dominant-style communicators may be critical and demanding, but they appreciate quality work; neurotic dominant communicators feel threatened by quality and are impossible to please.

To summarize, the dominant style is most successful when untrained subordinates need their expertise, during a crisis or time of organizational change, or when an immediate decision is needed. The dominant style is less successful when the organization has many personnel problems, when subordinates are professional people who expect to make their own decisions, or when creativity and risk taking are critical to the organization’s success.

The Sociable Style

If you had to choose between an efficient, highly productive office in which people were friendly but not social, or a less efficient but social environment in which birthdays were celebrated, employees freely chatted while working, and everyone was treated as a family member, which would you pick? People with sociable tendencies prefer a social environment and want to be friendly with everyone as is found in the human relations model. Sociable-style communicators are interested in people, are good listeners, and are generally well liked. It’s very important to them that everyone gets along and that conflicts are avoided. However, sociable-style communicators may limit what they choose to share and may hide their

“true” feelings and knowledge from others.

Sociable-style communicators fall on the low-disclosure/assertiveness, high-feedback/responsiveness ends of the two continuums. Although they like social environments, they find it difficult to disclose their opinions and expectations to others. For example, a sociable- style boss may cover only strengths in an employee appraisal and skip over weaknesses; a sociable-style employee may be unable to disagree with an unfair comment from the boss during an appraisal; and a sociable-style customer may agree with a salesperson’s suggestions even if they don’t reflect what the customer prefers.

Don’t confuse the sociable communicator with the private communicator. Sociable communicators are not afraid of people, and they don’t hide from them like the private style communicator does. They do listen carefully to others and ask them how they feel, but they tend to keep their own opinions and feelings private—does this sound like you?

Why do sociable-style people hide their opinions and feelings from others? They are motivated by mistrust of people or by the desire for social acceptance—or even both. Sociable people who tend to mistrust others feel more comfortable when they know what people are up to; they want to find out what is going on and to get feedback—someone is bound to let something slip. For example, a sociable-style customer who is motivated by mistrust will be suspicious that the salesperson is taking advantage in some way and will try to confirm these suspicions by asking questions.

Sociable-style people who are motivated by the desire for social acceptance want, above all, to please others. For example, sociable-style managers feel that keeping people happy is more important than productivity. After all, employee complaints can get you fired; moderate productivity usually doesn’t. Sociable-style customers who are motivated by a desire for social acceptance would rather deal with friendly, sociable salespeople even if they have to pay more for the product.

Sociable-style people often appear to be sharing because they ask questions and stimulate others to share, thereby disguising their lack of disclosure. Sociable people disclose only on impersonal, safe topics and don’t disagree with others. Sociable-style employees often appear overly friendly and eager to please (“yes” people). Sociable-style managers create the facade of being open in meetings when important decisions are to be made, but they usually speak up only after the majority opinion is clear or the top bosses’ views are known. Sociable people fear conflict and disagreement and try to smooth over any discord.

As you can see, relationships with sociable-style people are basically one-way; they do most of the listening, while others do most of the sharing. Often, when others realize this, they withdraw their trust or at least stop confiding as much to the sociable-style person.

To summarize, the sociable style is most successful when a social environment is expected; when the climate of the organization makes caution and political maneuvering necessary; when teamwork is a social occasion and rarely involves problem solving; and when adequate performance is all that

is expected. The sociable style is less successful when the climate is more work-oriented that social; when tasks require a high degree of trust among workers; when tasks are complex and involve team problem solving; and when excellent performance is expected.

The Open Style

Open-style communicators tend to use both disclosure and feedback and are equally interested in people’s needs and company productivity. Of the four styles, open-style communicators are the ones who most appreciate other people (private communicators are nervous around people, dominant communicators tend to view others as relatively unimportant, and sociable communicators don’t always trust people). Open-style communicators fall on the high-disclosure/assertiveness, high-feedback/responsiveness ends of the two continuums. In fact, they may disclose too much too often and may ask for too much feedback. This type of forward communication makes many people uncomfortable—like the stranger sitting next to you on an airplane who tells you all about his or her family, latest surgery, and marital affair.

For most open-style people, the problem is not that they are too open but that they are too open too soon. In The Open Organization, Steele (1975) warns that the order in which we disclose different aspects of ourselves will determine how others react to us. For instance, new members of a group should first show their responsible, concerned side. When this stance results in their acceptance, they can then start to show their less perfect aspects and even make a critical observation. These same aspects or observations could get a nonmember rejected out of hand. For example, mentioning a problem you observed to your colleagues when you are a new hire of less than a week would likely get more of a negative response than if you had worked for the company for 2 to 3 months. In new environments, open-style employees need to listen and observe others to determine

the openness of the climate. Openness is most effective when it produces a gradual sharing with others.

Open-style people are generally sensitive to the needs of others and realize that conflict can be productive. Open-style managers are more likely to empower employees to take active roles in the affairs of the organization. These empowered employees usually develop quality relationships and increase productivity. Generally, “employees in open, supportive communication climates are satisfied employees” (Conrad & Poole, 2012, p.143; see also Daft & Marcic, 2015).

Do not assume from what has been said so far that the open style is advocated in all situations. If the organization’s climate is open, if upper management favors the open style, if employees and managers are basically open, and if customers appreciate an open style, then the open style is appropriate. Within reason, the more open we are, the better communicators we are likely to be because we are better able to share our frames of reference and expectations with others. Many organizations, however, do not have an open climate. Upper management may not approve of open-style managers and may fail to promote them. Some employees may be uncomfortable around open managers and consider their requests for employee input as proof that they cannot make decisions. Some customers consider open-style salespeople as pushy or even nosy. But keep in mind that what is too open for one group may be just right for another.

In general, a moderately open style is most successful when employee involvement in decision making is desired; when change is welcomed as a new opportunity; when tasks are complex and require teamwork; when quality work is expected; and when the organization is involved in global communication using one of the transformational models. The open style is less successful when upper managers or workers view the open style negatively; when tasks are extremely simple and require no teamwork; and when an immediate decision is needed.

Important Tips on Using Communication Styles in the Workplace

Your communication success and your ability to establish and maintain relationships both at home and in the workplace depend on realizing two important facts about communication styles:

Fact one: All communication styles have strengths and all have weaknesses. Realizing this simple fact indicates to all communicators that we should analyze our own strengths and weaknesses to see whether any changes are needed. This knowledge also indicates the need for flexibility when dealing with other people who also have styles with strengths and weaknesses.

Fact two: Successful relationships depend on our knowing how to relate to people of different styles. Therefore, this section includes both the best and worst of each style as well as some suggested ways to relate to managers, employees, and customers in our lives who use different communication styles.

Tips for Communicating with Private-Style People

How to communicate with private-style managers: Take care—don’t threaten them or increase their insecurity. Avoid asking questions—better to ask other employees if you can do so quietly or make the decision yourself. Don’t make waves—better to downplay new procedures you develop. Don’t expect any praise, guidance, criticism, or help from the boss— better to provide these for yourself.

How to communicate with private-style employees: Put closed employees in environments that feel safe—that require little interaction with others. Give specific instructions about how, what, when, and where. Make the chain of command clear—to whom are they responsible? Limit criticism—they are

overcritical of themselves already. Don’t expect their participation in meetings or appraisal interviews.

How to communicate with private-style customers: Don’t expect them to openly express what they really want—you must search for it. Help them make good choices and you could have a customer for life. Avoid technical jargon—they may be overwhelmed by it. A flip chart presentation may give

them a sense of security—avoid a team presentation—it may increase their insecurity. Treat them with respect.

Tips for Communicating with Dominant-Style People

How to communicate with dominant style managers: Take their criticism well and expect to learn from them. Meet the dominant manager’s expectations. Accept that your proposals will be changed by the boss. Ask questions to see what information the boss has assumed you already know and to determine whether the boss already has a “correct” solution in mind. If the boss is a neurotic blind type (a closed boss pretending to be blind), expect personal attacks on your ego.

How to communicate with dominant style employees: Expect that dominant employees are very self-assured, often argumentative, and usually not team players but know the rules of the game and can play when it is to their advantage. Encourage them to deal with others more flexibly because these employees could well become managers in the future. Show them that you will reward team involvement. Let them see that you are in charge but that you appreciate the skills and knowledge of others.

How to communicate with dominant style customers: Give a polished, well-supported sales presentation—avoid reading a canned flip chart presentation. A team approach, if professional, will probably impress them. Be prepared for suggestions on how to improve your selling technique. Dominant customers like to feel in control; let them feel that they negotiated an exceptional deal (they probably did). Don’t keep them waiting.

Tips for Communicating with Sociable-Style People

How to communicate with sociable style managers: If you are too knowledgeable or have come from another department, you may be considered a spy. You will not always know where you stand. Don’t expect the boss to disclose fully—watch for nonverbal signs that the boss could say more. Show

how your work or ideas will bring recognition to the department and thus to the boss, who wants social acceptance. Don’t be afraid to use tactful confrontation; the boss will often back down.

How to communicate with sociable employees motivated by desire for social acceptance: Expect these employees to be “yes” people because they believe that pleasing you and others is the way to success. Motivate them by public praise (but criticism given in private), posting their names on a wall chart, asking them to give special talks, and other actions that will enhance their social acceptance. Show that you feel positive toward them. How to communicate with sociable employees motivated by lack of trust: Realize that sociable-style employees are hard to spot because they have learned how to play the game. Demonstrate (by promotions and performance appraisals) that honest team cooperation is the way to get ahead. Establish a climate in which differing opinions will not be penalized. Expect your comments to be searched for a double meaning. Be specific, use examples, don’t assume meanings are clear.

How to communicate with sociable-style customers: Spend time establishing a friendly feeling before giving your pitch. Use referral—they are more likely to buy if they feel that others they respect are sold on the idea, product, or service. Listen carefully and keep your opinions out of the picture (at least until the client’s views are known) because hidden customers may say they agree even if they don’t.

Tips for Communicating with Open-Style People

How to communicate with open managers: Be honest and open, but use tact. Look at all sides of a problem. Don’t hesitate to share job feelings, doubts, or concerns. Share part of your personal life; follow the boss’s lead. Accept shared responsibility and power.

How to communicate with open employees: Share confidences—open employees respond well. Place them in an environment in which some friendships can develop. Give them constructive criticism—they usually want to improve and are the first to sign up for special courses offered by the company. Employees who are too open may talk too much, but don’t assume that people can’t talk and work at the same time—some talkative employees are more productive than quiet ones.

How to communicate with open customers: Don’t be pushy or manipulative. Listen carefully to their needs and wants—they are usually able to articulate them well. Build your persuasive appeals around these needs. Treat them as equals—don’t talk down or defer to them. Canned flip chart presentations may be tolerated but are normally not impressive. Open customers are less impressed by flashiness and more impressed by facts—brief demonstrations can work well.

Becoming Flexible in Use of Styles

The key to good communication is flexibility in use of styles. There is a big difference between being private, dominant, sociable, or open because that is the style we generally use and deliberately choosing a certain style because it best suits the needs of the individual or group with whom we are dealing.

When you complete the Polishing Your Career Skill survey, you may discover that your style does not match your work environment. If so, you may be down to two choices: either change your job (remember, we tend to become like the environment in which we spend our time) or adapt your style. The latter is a good choice even if a job change is in order; flexibility may well be your key to effective communication wherever you work. However, we don’t recommend that you try a complete style change, at least not all at once. Before making any change, you should get enough feedback to be sure that a change is warranted and then start gradually. Adapt some of your responses to mirror those used by a person with a different style. When you feel comfort able with that new behavior, try another one. Communication behaviors can be changed, but not without hard work and patience. Few people find it easy to break an old habit. For example, a person with strong dominant tendencies can learn to communicate in an open style and even solve conflict in a collaborative manner but will normally retain some dominant-style behaviors, especially in times of stress

Adapting or changing a style will require changes in your use of feedback, disclosure, or both

- The person with dominant tendencies needs to ask for more feedback from others to discover areas needing change.

- The person with sociable tendencies needs to disclose more and should slowly begin to share more information, opinions, and feelings with others

- People with private or open styles need to work equally on both feedback and disclosure; the private person to use more of each, and the overly open person to use less of each.

Page Attribution

- Cheryl Hamilton’s Communicating for results: A guide for business and the professions (11th Ed.) Chapter 3.

Media Attributions

- Hamiton picture

- image 2

- The manager, employee, and customer styles presented in this section are a composite of Luft and Ingham’s (Luft, 1969) “JoHari window” concept; J. A. Hall’s (1975) “interpersonal styles and managerial impacts;” Lefton’s (Lefton, Buzzotta, Sherberg, & Karraker, 1980) “management systems approach;” Bradford and Cohen’s (1984) “manageras- conductor” and “manager-as-developer” middle manager style; and Merrill & Reid’s (1981) “Social Style Model” (SSM). The final result is Hamilton’s own product updated in 2011 and, therefore, does not parallel any of the other approaches exactly. ↵