Chapter 8: Professional Presentations in Organizations

8.2 Content: Research and Support

We live in an age where access to information is more convenient than ever before. The days of photocopying journal articles in the stacks of the library or looking up newspaper articles on microfilm are over for most. Yet, even though we have all this information at our fingertips, research skills are more important than ever. Our challenge now is not accessing information but discerning what information is credible and relevant. Even though it may sound inconvenient to have to physically go to the library, students who did research before the digital revolution did not have to worry as much about discerning. If you found a source in the library, you could be assured of its credibility because a librarian had subscribed to or purchased that content. When you use Internet resources like Google or Wikipedia, you have no guarantees about some of the content that comes up.

Finding Supporting Material

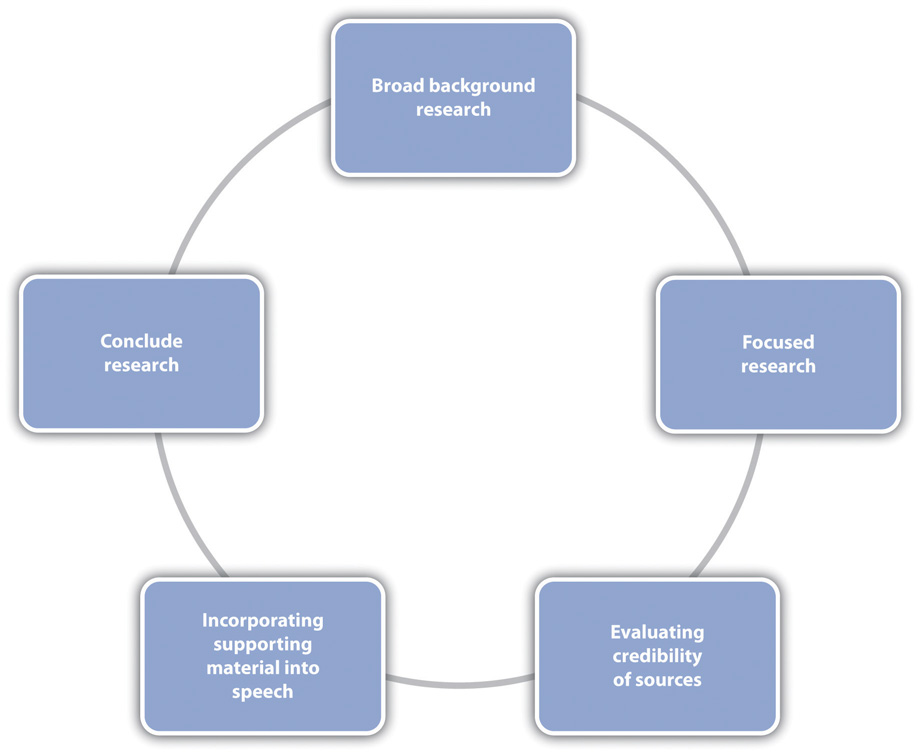

Depending on how familiar you are with a topic, you will need to do more or less background research before you actually start incorporating sources to support your speech. Background research is just a review of summaries available for your topic that helps refresh or create your knowledge about the subject. It is not the more focused and academic research that you will actually use to support and verbally cite in your speech. Figure 8.3 “Research Process” illustrates the research process. Note that you may go through some of these steps more than once.

I will reiterate several times in this chapter that your first step for research in college should be library resources, not Google or Bing or other general search engines. In most cases, you can still do your library research from the comfort of a computer, which makes it as accessible as Google but gives you much better results. Excellent and underutilized resources at college and university libraries are reference librarians. Reference librarians are not like the people who likely staffed your high school library. They are information-retrieval experts. At most colleges and universities, you can find a reference librarian who has at least a master’s degree in library and information sciences, and at some larger or specialized schools, reference librarians have doctoral degrees. I liken research to a maze, and reference librarians can help you navigate the maze. There may be dead ends, but there’s always another way around to reach the end goal. Unfortunately, many students hit their first dead end and give up or assume that there’s not enough research out there to support their speech. Trust me, if you’ve thought of a topic to do your speech on, someone else has thought of it, too, and people have written and published about it. Reference librarians can help you find that information. I recommend that you meet with a reference librarian face-to-face and take your assignment sheet and topic idea with you. In most cases, students report that they came away with more information than they needed, which is good because you can then narrow that down to the best information. If you can’t meet with a reference librarian face-to-face, many schools now offer the option to do a live chat with a reference librarian, and you can also contact them by e-mail or phone.

Aside from the human resources available in the library, you can also use electronic resources such as library databases. Library databases help you access more credible and scholarly information than what you will find using general Internet searches. These databases are quite expensive, and you can’t access them as a regular citizen without paying for them. Luckily, some of your tuition dollars go to pay for subscriptions to these databases that you can then access as a student. Through these databases, you can access newspapers, magazines, journals, and books from around the world. Of course, libraries also house stores of physical resources like DVDs, books, academic journals, newspapers, and popular magazines. You can usually browse your library’s physical collection through an online catalog search. A trip to the library to browse is especially useful for books. Since most university libraries use the Library of Congress classification system, books are organized by topic. That means if you find a good book using the online catalog and go to the library to get it, you should take a moment to look around that book, because the other books in that area will be topically related. On many occasions, I have used this tip and gone to the library for one book but left with several.

Although Google is not usually the best first stop for conducting college-level research, Google Scholar is a separate search engine that narrows results down to scholarly materials. This version of Google has improved much over the past few years and has served as a good resource for my research, even for this book. A strength of Google Scholar is that you can easily search for and find articles that aren’t confined to a particular library database. Basically, the pool of resources you are searching is much larger than what you would have using a library database. The challenge is that you have no way of knowing if the articles that come up are available to you in full-text format. As noted earlier, most academic journal articles are found in databases that require users to pay subscription fees. So you are often only able to access the abstracts of articles or excerpts from books that come up in a Google Scholar search. You can use that information to check your library to see if the article is available in full-text format, but if it isn’t, you have to go back to the search results. When you access Google Scholar on a campus network that subscribes to academic databases, however, you can sometimes click through directly to full-text articles. Although this resource is still being improved, it may be a useful alternative or backup when other search strategies are leading to dead ends.

Researching your topic

Nonacademic Information Sources

Nonacademic information sources are sometimes also called popular press information sources; their primary purpose is to be read by the general public. Most nonacademic information sources are written at a sixth- to eighth-grade reading level, so they are very accessible. Although the information often contained in these sources is often quite limited, the advantage of using nonacademic sources is that they appeal to a broad, general audience.

Books

The first source we have for finding secondary information is books. Now, the authors of your text are admitted bibliophiles—we love books. Fiction, nonfiction, it doesn’t really matter, we just love books. And, thankfully, we live in a world where books abound and reading has never been easier. Unless your topic is very cutting-edge, chances are someone has written a book about your topic at some point in history.

Historically, the original purpose of libraries was to house manuscripts that were copied by hand and stored in library collections. After Gutenberg created the printing press, we had the ability to mass produce writing, and the handwritten manuscript gave way to the printed manuscript. In today’s modern era, we are seeing another change where printed manuscript is now giving way, to some extent, to the electronic manuscript. Amazon.com’s Kindle, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Apple’s iPad, and Sony’s e-Ink-based readers are examples of the new hardware enabling people to take entire libraries of information with them wherever they go. We now can carry the amount of information that used to be housed in the greatest historic libraries in the palms of our hands. When you sit back and really think about it, that’s pretty darn cool!

In today’s world, there are three basic types of libraries you should be aware of: physical library, physical/electronic library, and e-online library. The physical library is a library that exists only in the physical world. Many small community or county library collections are available only if you physically go into the library and check out a book. We highly recommend doing this at some point. Libraries today generally model the US Library of Congress’s card catalog system. As such, most library layouts are similar. This familiar layout makes it much easier to find information if you are using multiple libraries. Furthermore, because the Library of Congress catalogs information by type, if you find one book that is useful for you, it’s very likely that surrounding books on the same shelf will also be useful. When people don’t take the time to physically browse in a library, they often miss out on some great information.

The second type of library is the library that has both physical and electronic components. Most college and university libraries have both the physical stacks (where the books are located) and electronic databases containing e-books. The two largest e-book databases are ebrary (http://www.ebrary.com) and NetLibrary (http://www.netlibrary.com). Although these library collections are generally cost-prohibitive for an individual, more and more academic institutions are subscribing to them. Some libraries are also making portions of their collections available online for free: Harvard University’s Digital Collections (http://digitalcollections.harvard.edu), New York Public Library’s E-book Collection (http://ebooks.nypl.org), The British Library’s Online Gallery (http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/virtualbooks/index.html#), and the US Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov).

One of the greatest advantages to using libraries for finding books is that you can search not only their books, but often a wide network of other academic institutions’ books as well. Furthermore, in today’s world, we have one of the greatest online card catalogs ever created—and it wasn’t created for libraries at all! Retail bookseller sites like Amazon.com can be a great source for finding books that may be applicable to your topic, and the best part is, you don’t actually need to purchase the book if you use your library, because your library may actually own a copy of a book you find on a bookseller site. You can pick a topic and then search for that topic on a bookseller site. If you find a book that you think may be appropriate, plug that book’s title into your school’s electronic library catalog. If your library owns the book, you can go to the library and pick it up today.

If your library doesn’t own it, do you still have an option other than buying the book? Yes: interlibrary loans. An interlibrary loan is a process where librarians are able to search other libraries to locate the book a researcher is trying to find. If another library has that book, then the library asks to borrow it for a short period of time. Depending on how easy a book is to find, your library could receive it in a couple of days or a couple of weeks. Keep in mind that interlibrary loans take time, so do not expect to get a book at the last minute. The more lead time you provide a librarian to find a book you are looking for, the greater the likelihood that the book will be sent through the mail to your library on time.

The final type of library is a relatively new one, the library that exists only online. With the influx of computer technology, we have started to create vast stores of digitized content from around the world. These online libraries contain full-text documents free of charge to everyone. Some online libraries we recommend are Project Gutenberg (http://www.gutenberg.org), Google Books (http://books.google.com), Read Print (http://www.readprint.com), Open Library (http://openlibrary.org), and Get Free e-Books (http://www.getfreeebooks.com). This is a short list of just a handful of the libraries that are now offering free e-content.

General-Interest Periodicals

The second category of information you may seek out includes general-interest periodicals. These are magazines and newsletters published on a fairly systematic basis. Some popular magazines in this category include The New Yorker, People, Reader’s Digest, Parade, Smithsonian, and The Saturday Evening Post. These magazines are considered “general interest” because most people in the United States could pick up a copy of these magazines and find them interesting and topical.

Special-Interest Periodicals

Special-interest periodicals are magazines and newsletters that are published for a narrower audience. In a 2005 article, Business Wire noted that in the United States there are over ten thousand different magazines published annually, but only two thousand of those magazines have significant circulation1. Some more widely known special-interest periodicals are Sports Illustrated, Bloomberg’s Business Week, Gentleman’s Quarterly, Vogue, Popular Science, and House and Garden. But for every major magazine, there are a great many other lesser-known magazines like American Coin Op Magazine, Varmint Hunter, Shark Diver Magazine, Pet Product News International, Water Garden News, to name just a few.

Newspapers and Blogs

Another major source of nonacademic information is newspapers and blogs. Thankfully, we live in a society that has a free press. We’ve opted to include both newspapers and blogs in this category. A few blogs (e.g., The Huffington Post, Talkingpoints Memo, News Max, The Daily Beast, Salon) function similarly to traditional newspapers. Furthermore, in the past few years we’ve lost many traditional newspapers around the United States; cities that used to have four or five daily papers may now only have one or two.

According to newspapers.com, the top ten newspapers in the United States are USA Today, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, the New York Daily News, the Chicago Tribune, the New York Post, Long Island Newsday, and the Houston Chronicle. Most colleges and universities subscribe to a number of these newspapers in paper form or have access to them electronically. Furthermore, LexisNexis, a database many colleges and universities subscribe to, has access to full text newspaper articles from these newspapers and many more around the world.

In addition to traditional newspapers, blogs are becoming a mainstay of information in today’s society. In fact, since the dawn of the twenty-first century many major news stories have been broken by professional bloggers rather than traditional newspaper reporters (Ochman, 2007). Although anyone can create a blog, there are many reputable blog sites that are run by professional journalists. As such, blogs can be a great source of information. However, as with all information on the Internet, you often have to wade through a lot of junk to find useful, accurate information.

We do not personally endorse any blogs, but according to Technorati.com, the top eight most commonly read blogs in the world (in 2011) are as follows:

- The Huffington Post (http://www.huffingtonpost.com)

- Gizmodo (http://www.gizmodo.com)

- TechCrunch (http://www.techcrunch.com)

- Mashable! (http://mashable.com)

- Engadget (http://www.engadget.com)

- Boing Boing (http://www.boingboing.net)

- The Daily Beast (http://www.thedailybeast.com)

- TMZ (http://www.tmz.com)

Encyclopedias

Another type of source that you may encounter is the encyclopedia. Encyclopedias are information sources that provide short, very general information about a topic. Encyclopedias are available in both print and electronic formats, and their content can range from eclectic and general (e.g., Encyclopædia Britannica) to the very specific (e.g., Encyclopedia of 20th Century Architecture, or Encyclopedia of Afterlife Beliefs and Phenomena). It is important to keep in mind that encyclopedias are designed to give only brief, fairly superficial summaries of a topic area. Thus they may be useful for finding out what something is if it is referenced in another source, but they are generally not a useful source for your actual speech. In fact, many instructors do not allow students to use encyclopedias as sources for their speeches for this very reason.

A popular online encyclopedia-like source is Wikipedia. Like other encyclopedias, it can be useful for finding out basic information (e.g., what baseball teams did Catfish Hunter play for?) but will not give you the depth of information you need for a speech. Also keep in mind that Wikipedia, unlike the general and specialized encyclopedias available through your library, can be edited by anyone and therefore often contains content errors and biased information. If you are a fan of The Colbert Report, you probably know that host Stephen Colbert has, on several occasions, asked viewers to change Wikipedia content to reflect his views of the world. This is just one example of why one should always be careful of information on the web, and why Wikipedia is not considered a credible source for college-level work.

Websites

Websites are the last major source of nonacademic information. In the twenty-first century we live in a world where there is a considerable amount of information readily available at our fingertips. Unfortunately, you can spend hours and hours searching for information and never quite find what you’re looking for if you don’t devise an Internet search strategy. First, you need to select a good search engine to help you find appropriate information. Table 8.1 “Search Engines” contains a list of common search engines and the types of information they are useful for finding.

Table 8.1 Search Engines

| http://www.google.com | General search engines |

| http://www.yahoo.com | |

| http://www.bing.com | |

| http://www.ask.com | |

| http://www.about.com | |

| http://www.usa.gov | Searches US government websites |

| http://www.hon.ch/MedHunt | Searches only trustworthy medical websites |

| http://medlineplus.gov | Largest search engine for medical related research |

| http://www.bizrate.com | Comparison shopping search engine |

| http://prb.org | Provides statistics about the US population |

| http://artcyclopedia.com | Searches for art-related information |

| http://www.monster.com | Searches for job postings across job search websites |

Academic Information Sources

After nonacademic sources, the second major source for finding information comes from academics. The main difference between academic or scholarly information and the information you get from the popular press is oversight. In the nonacademic world, the primary gatekeeper of information is the editor, who may or may not be a content expert. In academia, we have established a way to perform a series of checks to ensure that the information is accurate and follows agreed-upon academic standards. For example, this book, or portions of this book, were read by dozens of academics who provided feedback. Having this extra step in the writing process is time consuming, but it provides an extra level of confidence in the relevance and accuracy of the information. In this section, we will discuss scholarly books and articles, computerized databases, and finding scholarly information on the web.

Scholarly Books

College and university libraries are filled with books written by academics. According to the Text and Academic Authors Association (http://www.taaonline.net), there are two types of scholarly books: textbooks and academic books. Textbooks are books that are written about a segment of content within a field of academic study and are written for undergraduate or graduate student audiences. These books tend to be very specifically focused. Take this book, for instance. We are not trying to introduce you to the entire world of human communication, just one small aspect of it: public speaking. Textbooks tend to be written at a fairly easy reading level and are designed to transfer information in a manner that mirrors classroom teaching to some extent. Also, textbooks are secondary sources of information. They are designed to survey the research available in a particular field rather than to present new research.

Academic books are books that are primarily written for other academics for informational and research purposes. Generally speaking, when instructors ask for you to find scholarly books, they are referring to academic books. Thankfully, there are hundreds of thousands of academic books published on almost every topic you can imagine. In the field of communication, there are a handful of major publishers who publish academic books: SAGE (http://www.sagepub.com), Routledge (http://www.routledge.com), Jossey-Bass (http://www.josseybass.com), Pfeiffer (http://www.pfeiffer.com), the American Psychological Association (http://www.apa.org/pubs/books), and the National Communication Association (http://www.ncastore.com), among others. In addition to the major publishers who publish academic books, there are also many university presses who publish academic books: SUNY Press (http://www.sunypress.edu), Oxford University Press (http://www.oup.com/us), University of South Carolina Press (http://www.sc.edu/uscpress), Baylor University Press (http://www.baylorpress.com), University of Illinois Press (http://www.press.uillinois.edu), and the University of Alabama Press (http://www.uapress.ua.edu) are just a few of them.

Scholarly Articles

Because most academic writing comes in the form of scholarly articles or journal articles, that is the best place for finding academic research on a given topic. Every academic subfield has its own journals, so you should never have a problem finding the best and most recent research on a topic. However, scholarly articles are written for a scholarly audience, so reading scholarly articles takes more time than if you were to read a magazine article in the popular press. It’s also helpful to realize that there may be parts of the article you simply do not have the background knowledge to understand, and there is nothing wrong with that. Many research studies are conducted by quantitative researchers who rely on statistics to examine phenomena. Unless you have training in understanding the statistics, it is difficult to interpret the statistical information that appears in these articles. Instead, focus on the beginning part of the article where the author(s) will discuss previous research (secondary research), and then focus at the end of the article, where the author(s) explain what was found in their research (primary research).

Computerized Databases

Finding academic research is easier today than it ever has been in the past because of large computer databases containing research. Here’s how these databases work. A database company signs contracts with publishers to gain the right to store the publishers’ content electronically. The database companies then create thematic databases containing publications related to general areas of knowledge (business, communication, psychology, medicine, etc.). The database companies then sell subscriptions to these databases to libraries.

The largest of these database companies is a group called EBSCO Publishing, which runs both EBSCO Host (an e-journal provider) and NetLibrary (a large e-book library) (http://www.ebscohost.com). Some of the more popular databases that EBSCO provides to colleges and universities are: Academic Search Complete, Business Source Complete, Communication and Mass Media Complete, Education Research Complete, Humanities International Complete, Philosopher’s Index, Political Science Complete, PsycArticles, and Vocational and Career Collection. Academic Search Complete is the broadest of all the databases and casts a fairly wide net across numerous fields. Information that you find using databases can contain both nonacademic and academic information, so EBSCO Host has built in a number of filtering options to help you limit the types of information available.

We strongly recommend checking out your library’s website to see what databases they have available and if they have any online tutorials for finding sources using the databases to which your library subscribes.

Scholarly Information on the Web

In addition to the subscription databases that exist on the web, there are also a number of great sources for scholarly information on the web. As mentioned earlier, however, finding scholarly information on the web poses a problem because anyone can post information on the web. Fortunately, there are a number of great websites that attempt to help filter this information for us.

| Website | Type of Information |

|---|---|

| http://www.doaj.org | The Directory of Open Access Journals is an online database of all freely available academic journals online. |

| http://scholar.google.com | Google Scholar attempts to filter out nonacademic information. Unfortunately, it tends to return a large number of for-pay site results. |

| http://www.cios.org | Communication Institute for Online Scholarship is a clearinghouse for online communication scholarship. This site contains full-text journals and books. |

| http://xxx.lanl.gov | This is an open access site devoted to making physical science research accessible. |

| http://www.biomedcentral.com | BioMed Central provides open-access medical research. |

| http://www.osti.gov/eprints | The E-print Network provides access to a range of scholarly research that interests people working for the Department of Energy. |

| http://www.freemedicaljournals.com | This site provides the public with free access to medical journals. |

| http://highwire.stanford.edu | This is the link to Stanford University’s free, full-text science archives. |

| http://www.plosbiology.org | This is the Public Library of Science’s journal for biology. |

| https://dp.la/ | The Digital Public Library of America brings together the riches of America’s libraries, archives, and museums, and makes them freely available to the world |

| http://vlib.org | The WWW Virtual Library provides annotated lists of websites compiled by scholars in specific areas. |

Tips for Finding Information Sources

Now that we’ve given you plenty of different places to start looking for research, we need to help you sort through the research. In this section, we’re going to provide a series of tips that should make this process easier and help you find appropriate information quickly. And here is our first tip: We cannot recommend Mary George’s book The Elements of Library Research: What Every Student Needs to Know more highly. Honestly, we wish this book had been around when we were just learning how to research.

Create a Research Log

Nothing is more disheartening than when you find yourself at 1:00 a.m. asking, “Haven’t I already read this?” We’ve all learned the tough lessons of research, and this is one that keeps coming back to bite us in the backside if we’re not careful. According to a very useful book called The Elements of Library Research by M. W. George, a research log is a “step-by-step account of the process of identifying, obtaining, and evaluating sources for a specific project, similar to a lab note-book in an experimental setting” (George, 2008). In essence, George believes that keeping a log of what you’ve done is very helpful because it can help you keep track of what you’ve read thus far. You can use a good old-fashioned notebook, or if you carry around your laptop or netbook with you, you can always keep it digitally. While there are expensive programs like Microsoft Office OneNote that can be used for note keeping, there are also a number of free tools that could be adapted as well.

Start with Background Information

It’s not unusual for students to try to jump right into the meat of a topic, only to find out that there is a lot of technical language they just don’t understand. For this reason, you may want to start your research with sources written for the general public. Generally, these lower-level sources are great for background information on a topic and are helpful when trying to learn the basic vocabulary of a subject area.

Search Your Library’s Computers

Once you’ve started getting a general grasp of the broad content area you want to investigate, it’s time to sit down and see what your school’s library has to offer. If you do not have much experience in using your library’s website, see if the website contains an online tutorial. Most schools offer online tutorials to show students the resources that students can access. If your school doesn’t have an online tutorial, you may want to call your library and schedule an appointment with a research librarian to learn how to use the school’s computers. Also, if you tell your librarian that you want to learn how to use the library, he or she may be able to direct you to online resources that you may have missed.

Try to search as many different databases as possible. Look for relevant books, e-books, newspaper articles, magazine articles, journal articles, and media files. Modern college and university libraries have a ton of sources, and one search may not find everything you are looking for on the first pass. Furthermore, don’t forget to think about synonyms for topics. The more synonyms you can generate for your topic, the better you’ll be at finding information.

Learn to Skim

If you sit down and try to completely read every article or book you find, it will take you a very long time to get through all the information. Start by reading the introductory paragraphs. Generally, the first few paragraphs will give you a good idea about the overall topic. If you’re reading a research article, start by reading the abstract. If the first few paragraphs or abstract don’t sound like they’re applicable, there’s a good chance the source won’t be useful for you. Second, look for highlighted, italicized, or bulleted information. Generally, authors use highlighting, italics, and bullets to separate information to make it jump out for readers. Third, look for tables, charts, graphs, and figures. All these forms are separated from the text to make the information more easily understandable for a reader, so seeing if the content is relevant is a way to see if it helps you. Fourth, look at headings and subheadings. Headings and subheadings show you how an author has grouped information into meaningful segments. If you read the headings and subheadings and nothing jumps out as relevant, that’s another indication that there may not be anything useful in that source. Lastly, take good notes while you’re skimming. One way to take good notes is to attach a sticky note to each source. If you find relevant information, write that information on the sticky note along with the page number. If you don’t find useful information in a source, just write “nothing” on the sticky note and move on to the next source. This way when you need to sort through your information, you’ll be able to quickly see what information was useful and locate the information. Other people prefer to create a series of note cards to help them organize their information. Whatever works best for you is what you should use.

Read Bibliographies/Reference Pages

After you’ve finished reading useful sources, see who those sources cited on their bibliographies or reference pages. We call this method backtracking. Often the sources cited by others can lead us to even better sources than the ones we found initially.

Ask for Help

Don’t be afraid to ask for help. As we said earlier in this chapter, reference librarians are your friends. They won’t do your work for you, but they are more than willing to help if you ask.

Evaluating Resources

The final step in research occurs once you’ve found resources relevant to your topic: evaluating the quality of those resources. Below is a list of six questions to ask yourself about the sources you’ve collected; these are drawn from the book The Elements of Library Research by M. W. George (Geogre, 2008).

What Is the Date of Publication?

The first question you need to ask yourself is the date of the source’s publication. Although there may be classic studies that you want to cite in your speech, generally, the more recent the information, the better your presentation will be. As an example, if you want to talk about the current state of women’s education in the United States, relying on information from the 1950s that debated whether “coeds” should attend class along with male students is clearly not appropriate. Instead you’d want to use information published within the past five to ten years.

Who Is the Author?

The next question you want to ask yourself is about the author. Who is the author? What are her or his credentials? Does he or she work for a corporation, college, or university? Is a political or commercial agenda apparent in the writing? The more information we can learn about an author, the better our understanding and treatment of that author’s work will be. Furthermore, if we know that an author is clearly biased in a specific manner, ethically we must tell our audience members. If we pretend an author is unbiased when we know better, we are essentially lying to our audience.

Who Is the Publisher?

In addition to knowing who the author is, we also want to know who the publisher is. While there are many mainstream publishers and academic press publishers, there are also many fringe publishers. For example, maybe you’re reading a research report published by the Cato Institute. While the Cato Institute may sound like a regular publisher, it is actually a libertarian think tank (http://www.cato.org). As such, you can be sure that the information in its publications will have a specific political bias. While the person writing the research report may be an upstanding author with numerous credits, the Cato Institute only publishes reports that adhere to its political philosophy. Generally, a cursory examination of a publisher’s website is a good indication of the specific political bias. Most websites will have an “About” section or an “FAQ” section that will explain who the publisher is.

Is It Academic or Nonacademic?

The next question you want to ask yourself is whether the information comes from an academic or a nonacademic source. Because of the enhanced scrutiny academic sources go through, we argue that you can generally rely more on the information contained in academic sources than nonacademic sources. One very notorious example of the difference between academic versus nonacademic information can be seen in the problem of popular-culture author John Gray, author of Men are From Mars, Women are From Venus. Gray, who received a PhD via a correspondence program from Columbia Pacific University in 1982, has written numerous books on the topic of men and women. Unfortunately, the academic research on the subject of sex and gender differences is often very much at odds with Gray’s writing. For a great critique of Gray’s writings, check out Julia Wood’s article in the Southern Communication Journal (Wood, 2002). Ultimately, we strongly believe that using academic publications is always in your best interest because they generally contain the most reliable information.

What Is the Quality of the Bibliography/Reference Page?

Another great indicator of a well-thought-out and researched source is the quality of its bibliography or reference page. If you look at a source’s bibliography or reference page and it has only a couple of citations, then you can assume that either the information was not properly cited or it was largely made up by someone. Even popular-press books can contain great bibliographies and reference pages, so checking them out is a great way to see if an author has done her or his homework prior to writing a text. As noted above, it is also an excellent way to find additional resources on a topic.

Do People Cite the Work?

The last question to ask about a source is, “Are other people actively citing the work?” One way to find out whether a given source is widely accepted is to see if numerous people are citing it. If you find an article that has been cited by many other authors, then clearly the work has been viewed as credible and useful. If you’re doing research and you keep running across the same source over and over again, that is an indication that it’s an important study that you should probably take a look at. Many colleges and universities also subscribe to Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), or the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI), which are run through Institute for Scientific Information’s Web of Knowledge database service (http://isiwebofknowledge.com). All these databases help you find out where information has been cited by other researchers.

Every day, all around the country, people give speeches that contain generalities and vagueness. Students on your campus might claim that local policies are biased against students, but may not explain why. Politicians may make claims in their speeches about “family values” without defining what those values are or throw out statistics without giving credit to where they found those numbers. Indeed, the nonpartisan websites FactCheck.org and Politifact.com are dedicated to investigating and dispelling the claims that politicians make in their speeches.

In this chapter, we explore the nature of supporting ideas in public speaking and why support is essential to effective presentations. We will then discuss how to use support to build stronger arguments within a speech.

Why We Use Support

Speakers use support to help provide a foundation for their message. You can think of support as the legs on a table. Without the legs, the table becomes a slab of wood or glass lying on the ground; as such, it cannot fully serve the purpose of a table. In the same way, without support, a speech is nothing more than fluff. Audience members may ignore the speech’s message, dismissing it as just so much hot air. In addition to being the foundation that a speech stands on, support also helps us clarify content, increase speaker credibility, and make the speech more vivid.

To Clarify Content

The first reason to use support in a speech is to clarify content. Speakers often choose a piece of support because a previous writer or speaker has phrased something in a way that evokes a clear mental picture of the point they want to make. For example, suppose you’re preparing a speech about hazing in college fraternities. You may read your school’s code of student conduct to find out how your campus defines hazing. You could use this definition to make sure your audience understands what hazing is and what types of behaviors your campus identifies as hazing.

To Add Credibility

Another important reason to use support is because it adds to your credibility as a speaker. The less an audience perceives you as an expert on a given topic, the more important it is to use a range of support. By doing so, you let your audience know that you’ve done your homework on the topic.

At the same time, you could hurt your credibility if you use inadequate support or support from questionable sources. Your credibility will also suffer if you distort the intent of a source to try to force it to support a point that the previous author did not address. For example, the famous 1798 publication by Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population, has been used as support for various arguments far beyond what Malthus could have intended. Malthus’s thesis was that as the human population increases at a greater rate than food production, societies will go to war over scarce food resources (Malthus, 1798). Some modern writers have suggested that, according to the Malthusian line of thinking, almost anything that leads to a food shortage could lead to nuclear war. For example, better health care leads to longer life spans, which leads to an increased need for food, leading to food shortages, which lead to nuclear war. Clearly, this argument makes some giant leaps of logic that would be hard for an audience to accept.

For this reason, it is important to evaluate your support to ensure that it will not detract from your credibility as a speaker. Here are four characteristics to evaluate when looking at support options: accuracy, authority, currency, and objectivity.

Accuracy

One of the quickest ways to lose credibility in the eyes of your audience is to use support that is inaccurate or even questionably accurate. Admittedly, determining the accuracy of support can be difficult if you are not an expert in a given area, but here are some questions to ask yourself to help assess a source’s accuracy:

- Does the information within one piece of supporting evidence completely contradict other supporting evidence you’ve seen?

- If the support is using a statistic, does the supporting evidence explain where that statistic came from and how it was determined?

- Does the logic behind the support make sense?

One of this book’s authors recently observed a speech in which a student said, “The amount of pollution produced by using paper towels instead of hand dryers is equivalent to driving a car from the east coast to St. Louis.” The other students in the class, as well as the instructor, recognized that this information sounded wrong and asked questions about the information source, the amount of time it would take to produce this much pollution, and the number of hand dryers used. The audience demonstrated strong listening skills by questioning the information, but the speaker lost credibility by being unable to answer their questions.

Authority

The second way to use support in building your credibility is to cite authoritative sources—those who are experts on the topic. In today’s world, there are all kinds of people who call themselves “experts” on a range of topics. There are even books that tell you how to get people to regard you as an expert in a given industry (Lizotte, 2007). Today there are “experts” on every street corner or website spouting off information that some listeners will view as legitimate.

So what truly makes someone an expert? Bruce D. Weinstein, a professor at West Virginia University’s Center for Health Ethics and Law, defined expertise as having two senses. In his definition, the first sense of expertise is “knowledge in or about a particular field, and statements about it generally take the form, ‘S is an expert in or about D.’… The second sense of expertise refers to domains of demonstrable skills, and statements about it generally take the form, ‘S is an expert at skill D (Weinstein, 1993).’” Thus, to be an expert, someone needs to have considerable knowledge on a topic or considerable skill in accomplishing something.

As a novice researcher, how can you determine whether an individual is truly an expert? Unfortunately, there is no clear-cut way to wade through the masses of “experts” and determine each one’s legitimacy quickly. However, Table 8.4 “Who Is an Expert?” presents a list of questions based on the research of Marie-Line Germain that you can ask yourself to help determine whether someone is an expert (Germain, 2006).

| Questions to Ask Yourself | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Is the person widely recognizable as an expert? | ||

| 2. Does the person have an appropriate degree/training/certification to make her or him an expert? | ||

| 3. Is the person a member of a recognized profession in her or his claimed area of expertise? | ||

| 4. Has the person published articles or books (not self-published) on the claimed area of expertise? | ||

| 5. Does the person have appropriate experience in her or his claimed area of expertise? | ||

| 6. Does the person have clear knowledge about her or his claimed area of expertise? | ||

| 7. Is the person clearly knowledgeable about the field related to her or his claimed area of expertise? | ||

| 8. When all is said and done, does the person truly have the qualifications to be considered an expert in her or his claimed area of expertise? |

You don’t have to answer “yes” to all the preceding questions to conclude that a source is credible, but a string of “no” answers should be a warning signal. In a Columbia Journalism Review article, Allisa Quart raised the question of expert credibility regarding the sensitive subject of autism. Specifically, Quart questioned whether the celebrity spokesperson and autism advocate Jennifer McCarthy (http://www.generationrescue.org/) qualifies as an expert. Quart notes that McCarthy “insists that vaccines caused her son’s neurological disorder, a claim that has near-zero support in scientific literature” (Quart, 2010). Providing an opposing view is a widely read blog called Respectful Insolence (http://scienceblogs.com/insolence/), whose author is allegedly a surgeon/scientist who often speaks out about autism and “antivaccination lunacy.” Respectful Insolence received the 2008 Best Weblog Award from MedGagdet: The Internet Journal of Emerging Medical Technologies. We used the word “allegedly” when referring to the author of Respectful Insolence because as the website explains that the author’s name, Orac, is the “nom de blog of a (not so) humble pseudonymous surgeon/scientist with an ego just big enough to delude himself that someone, somewhere might actually give a rodent’s posterior about his miscellaneous verbal meanderings, but just barely small enough to admit to himself that few will” (ScienceBlogs LLC).

When comparing the celebrity Jenny McCarthy to the blogger Orac, who do you think is the better expert? Were you able to answer “yes” to the questions in Table 8.4 “Who Is an Expert?” for both “experts”? If not, why not? Overall, determining the authority of support is clearly a complicated task, and one that you should spend time thinking about as you prepare the support for your speech.

Currency

The third consideration in using support to build your credibility is how current the information is. Some ideas stay fairly consistent over time, like the date of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor or the mathematical formula for finding the area of a circle, but other ideas change wildly in a short period of time, including ideas about technology, health treatments, and laws.

Although we never want to discount classic supporting information that has withstood the test of time, as a general rule for most topics, we recommend that information be less than five years old. Obviously, this is just a general guideline and can change depending on the topic. If you’re giving a speech on the history of mining in West Virginia, then you may use support from sources that are much older. However, if you’re discussing a medical topic, then your support information should probably be from the past five years or less. Some industries change even faster, so the best support may come from the past month. For example, if are speaking about advances in word processing, using information about Microsoft Word from 2003 would be woefully out-of-date because two upgrades have been released since 2003 (2007 and 2010). As a credible speaker, it is your responsibility to give your audience up-to-date information.

Objectivity

The last question you should ask yourself when examining support is whether the person or organization behind the information is objective or biased. Bias refers to a predisposition or preconception of a topic that prevents impartiality. Although there is a certain logic to the view that every one of us is innately biased, as a credible speaker, you want to avoid just passing along someone’s unfounded bias in your speech. Ideally you would use support that is unbiased; Table 8.5 “Is a Potential Source of Support Biased?” provides some questions to ask yourself when evaluating a potential piece of support to detect bias.

| Questions to Ask Yourself | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Does the source represent an individual’s, an organization’s, or another group’s viewpoint? | ||

| 2. Does the source sound unfair in its judgment, either for or against a specific topic? | ||

| 3. Does the source sound like personal prejudices, opinions, or thoughts? | ||

| 4. Does the source exist only on a website (i.e., not in print or any other format)? | ||

| 5. Is the information published or posted anonymously or pseudonymously? | ||

| 6. Does the source have any political or financial interests related to the information being disseminated? | ||

| 7. Does the source demonstrate any specific political orientation, religious affiliation, or other ideology? | ||

| 8. Does the source’s viewpoint differ from all other information you’ve read? |

As with the questions in the “Who Is an Expert?” table about expertise, you don’t have to have all “no” or “yes” responses to decide on bias. However, being aware of the possibility of bias and where your audience might see bias will help you to select the best possible support to include in your speech.

To Add Vividness

In addition to clarifying content and enhancing credibility, support helps make a speech more vivid. Vividness refers to a speaker’s ability to present information in a striking, exciting manner. The goal of vividness is to make your speech more memorable. One of the authors still remembers a vivid example from a student speech given several years ago. The student was speaking about the importance of wearing seat belts and stated that the impact from hitting a windshield at just twenty miles per hour without a seat belt would be equivalent to falling out of the window of their second-floor classroom and landing face-first on the pavement below. Because they were in that classroom several times each week, students were easily able to visualize the speaker’s analogy and it was successful at creating an image that is remembered years later. Support helps make your speech more interesting and memorable to an audience member.

Types of Support

Tall Chris – magnifying glass – CC BY 2.0.

Now that we’ve explained why support is important, let’s examine the various types of support that speakers often use within a speech: facts and statistics, definitions, examples, narratives, testimony, and analogies.

Factual Material: Facts, Statistics & Definitions

A fact is a truth that is arrived at through the scientific process. Speakers often support a point or specific purpose by citing facts that their audience may not know. A typical way to introduce a fact orally is “Did you know that…?”

Many of the facts that speakers cite are based on statistics. Statistics is the mathematical subfield that gathers, analyzes, and makes inferences about collected data. Data can come in a wide range of forms—the number of people who buy a certain magazine, the average number of telephone calls made in a month, the incidence of a certain disease. Though few people realize it, much of our daily lives are governed by statistics. Everything from seat-belt laws, to the food we eat, to the amount of money public schools receive, to the medications you are prescribed are based on the collection and interpretation of numerical data.

It is important to realize that a public speaking textbook cannot begin to cover statistics in depth. If you plan to do statistical research yourself, or gain an understanding of the intricacies of such research, we strongly recommend taking a basic class in statistics or quantitative research methods. These courses will better prepare you to understand the various statistics you will encounter.

However, even without a background in statistics, finding useful statistical information related to your topic is quite easy. Table 8.3 “Statistics-Oriented Websites” provides a list of some websites where you can find a range of statistical information that may be useful for your speeches.

Table 8.3 Statistics-Oriented Websites

| Website | Type of Information |

|---|---|

| http://www.bls.gov/bls/other.htm | Bureau of Labor Statistics provides links to a range of websites for labor issues related to a vast range of countries. |

| http://bjs.gov | Bureau of Justice Statistics provides information on crime statistics in the United States. |

| http://www.census.gov | US Census Bureau provides a wide range of information about people living in the United States. |

| https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ | National Center for Health Statistics is a program conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It provides information on a range of health issues in the United States. |

| http://www.stats.org | STATS is a nonprofit organization that helps people understand quantitative data. It also provides a range of data on its website. |

| http://ropercenter.cornell.edu/ | Roper Center for Public Opinion provides data related to a range of issues in the United States. |

| http://www.nielsen.com | Nielsen provides data on consumer use of various media forms. |

| http://www.gallup.com | Gallup provides public opinion data on a range of social and political issues in the United States and around the world. |

| http://www.adherents.com | Adherents provides both domestic and international data related to religious affiliation. |

| http://people-press.org | Pew Research Center provides public opinion data on a range of social and political issues in the United States and around the world. |

Statistics are probably the most used—and misused—form of support in any type of speaking. People like numbers. People are impressed by numbers. However, most people do not know how to correctly interpret numbers. Unfortunately, there are many speakers who do not know how to interpret them either or who intentionally manipulate them to mislead their listeners. As the saying popularized by Mark Twain goes, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics” (Twain, 1924).

To avoid misusing statistics when you speak in public, do three things. First, be honest with yourself and your audience. If you are distorting a statistic or leaving out other statistics that contradict your point, you are not living up to the level of honesty your audience is entitled to expect. Second, run a few basic calculations to see if a statistic is believable. Sometimes a source may contain a mistake—for example, a decimal point may be in the wrong place or a verbal expression like “increased by 50 percent” may conflict with data showing an increase of 100 percent. Third, evaluate sources (even those in Table 8.3 “Statistics-Oriented Websites”, which are generally reputable) according to the criteria discussed earlier in the chapter: accuracy, authority, currency, and objectivity.

Definitions

A denotative definition is one that specifically states how a word is used within a specific language. For example, if you go to Dictionary.com and type in the word “speech,” here is the denotative (i.e. lexical) definition you will receive:

Speech

–nounthe faculty or power of speaking; oral communication; ability to express one’s thoughts and emotions by speech sounds and gesture: Losing her speech made her feel isolated from humanity.

the act of speaking: He expresses himself better in speech than in writing.

something that is spoken; an utterance, remark, or declaration: We waited for some speech that would indicate her true feelings.

a form of communication in spoken language, made by a speaker before an audience for a given purpose: a fiery speech.

any single utterance of an actor in the course of a play, motion picture, etc.

the form of utterance characteristic of a particular people or region; a language or dialect.

manner of speaking, as of a person: Your slovenly speech is holding back your career.a field of study devoted to the theory and practice of oral communication.

Lexical definitions are useful when a word may be unfamiliar to an audience and you want to ensure that the audience has a basic understanding of the word. However, our ability to understand lexical definitions often hinges on our knowledge of other words that are used in the definition, so it is usually a good idea to follow a lexical definition with a clear explanation of what it means in your own words.

Definitions are important to provide clarity for your audience. Effective speakers strike a balance between using definitions where they are needed to increase audience understanding and leaving out definitions of terms that the audience is likely to know. For example, you may need to define what a “claw hammer” is when speaking to a group of Cub Scouts learning about basic tools, but you would appear foolish—or even condescending—if you defined it in a speech to a group of carpenters who use claw hammers every day. On the other hand, just assuming that others know the terms you are using can lead to ineffective communication as well. Medical doctors are often criticized for using technical terms while talking to their patients without taking time to define those terms. Patients may then walk away not really understanding what their health situation is or what needs to be done about it.

Examples

Another often-used type of support is examples. An example is a specific situation, problem, or story designed to help illustrate a principle, method, or phenomenon. Examples are useful because they can help make an abstract idea more concrete for an audience by providing a specific case. Let’s examine three types of examples: brief, extended and hypothetical.

Brief Examples[2]

Brief examples are used to further illustrate a point that may not be immediately obvious to all audience members but is not so complex that is requires a more lengthy example. Brief examples can be used by the presenter as an aside or on its own. A presenter may use a brief example in a presentation on politics in explaining the Electoral College. Since many people are familiar with how the Electoral College works, the presenter may just mention that the Electoral College is based on population and a brief example of how it is used to determine an election. In this situation it would not be necessary for a presented to go into a lengthy explanation of the process of the Electoral College since many people are familiar with the process.

Extended Examples

Extended examples are used when a presenter is discussing a more complicated topic that they think their audience may be unfamiliar with. In an extended example a speaker may want to use a chart, graph, or other visual aid to help the audience understand the example. An instance in which an extended example could be used includes a presentation in which a speaker is explaining how the “time value of money” principle works in finance. Since this is a concept that people unfamiliar with finance may not immediately understand, a speaker will want to use an equation and other visual aids to further help the audience understand this principle. An extended example will likely take more time to explain than a brief example and will be about a more complex topic.

Hypothetical Examples

A hypothetical example is a fictional example that can be used when a speaker is explaining a complicated topic that makes the most sense when it is put into more realistic or relatable terms. For instance, if a presenter is discussing statistical probability, instead of explaining probability in terms of equations, it may make more sense for the presenter to make up a hypothetical example. This could be a story about a girl, Annie, picking 10 pieces of candy from a bag of 50 pieces of candy in which half are blue and half are red and then determining Annie’s probability of pulling out 10 total pieces of red candy. A hypothetical example helps the audience to better visualize a topic and relate to the point of the presentation more effectively

Examples are essential to a presentation that is backed up with evidence, and they help the audience effectively understand the message being presented. Examples are most effective when they are used as a complement to a key point in the presentation and focus on the important topics of the presentation. However, a speaker should be careful to not overuse examples, as too many examples may confuse the audience and distract them from focusing on the key points that the speaker is making.

Testimony

Another form of support you may employ during a speech is testimony. When we use the word “testimony” in this text, we are specifically referring to expert opinion or direct accounts of witnesses to provide support for your speech. Notice that within this definition, we refer to both expert and eyewitness testimony.

Expert Testimony

Expert testimony accompanies the discussion we had earlier in this chapter related to what qualifies someone as an expert. In essence, expert testimony expresses the attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors recommended by someone who is an acknowledged expert on a topic. For example, imagine that you’re going to give a speech on why physical education should be mandatory for all grades K–12 in public schools. During the course of your research, you come across The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Fit and Healthy Nation (http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/obesityvision/obesityvision2010.pdf). You might decide to cite information from within the report written by US Surgeon General Dr. Regina Benjamin about her strategies for combating the problem of childhood obesity within the United States. If so, you are using the words from Dr. Benjamin, as a noted expert on the subject, to support your speech’s basic premise. Her expertise is being used to give credibility to your claims.

Eyewitness Testimony

Eyewitness testimony, on the other hand, is given by someone who has direct contact with the phenomenon of your speech topic. Imagine that you are giving a speech on the effects of the 2010 “Deepwater Horizon” disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Perhaps one of your friends happened to be on a flight that passed over the Gulf of Mexico and the pilot pointed out where the platform was. You could tell your listeners about your friend’s testimony of what she saw as she was flying over the spill.

However, using eyewitness testimony as support can be a little tricky because you are relying on someone’s firsthand account, and firsthand accounts may not always be reliable. As such, you evaluate the credibility of your witness and the recency of the testimony.

To evaluate your witness’s credibility, you should first consider how you received the testimony. Did you ask the person for the testimony, or did he or she give you the information without being asked? Second, consider whether your witness has anything to gain from his or her testimony. Basically, you want to know that your witness isn’t biased.

Second, consider whether your witness’ account was recent or something that happened some time ago. With a situation like the BP oil spill, the date when the spill was seen from the air makes a big difference. If the witness saw the oil spill when the oil was still localized, he or she could not have seen the eventual scope of the disaster.

Overall, the more detail you can give about the witness and when the witness made his or her observation, the more useful that witness testimony will be when attempting to create a solid argument. However, never rely completely on eyewitness testimony because this form of support is not always the most reliable and may still be perceived as biased by a segment of your audience.

- "9.2 Researching and Supporting Your Speech". Introduction to Public Communication. Department of Communication, Indiana State University. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-communications/chapter/using-examples/ ↵