Chapter 1: Defining Communication and Communication Study

1.2 Defining Communication

Defining Communication

For decades communication professionals have had difficulty coming to any consensus about how to define the term communication (Hovland, 1948; Lasswell, 1949; Morris, 1946; Nilsen, 1957; Sapir, 1933 & Stevens, 1950). Even today, there is no single agreed-upon definition of communication. In 1970 and 1984, Frank Dance looked at 126 published definitions of communication in literature and said that the task of trying to develop a single definition of communication that everyone likes is like trying to nail jello to a wall. Thirty years later, defining communication still feels like nailing jello to a wall.

Communication Study Then: Aristotle The Communication Researcher

Aristotle said, “Rhetoric falls into three divisions, determined by the three classes of listeners to speeches. For of the three elements in speech-making — speaker, subject, and person addressed — it is the last one, the hearer, that determines the speech’s end and object.”

For Aristotle, it was the “to whom” that determined if communication occurred and how effective it was. Aristotle, in his study of “who says what, through what channels, to whom, and what will be the results” focused on persuasion and its effect on the audience. Aristotle thought it was extremely important to focus on the audience in communication exchanges.

What is interesting is that when we think of communication we are often, “more concerned about ourselves as the communication’s source, about our message, and even the channel we are going to use. Too often, the listener, viewer, reader fails to get any consideration at all” (Lee, 2008).

Aristotle’s statement above demonstrates that humans who have been studying communication have had solid ideas about how to communicate effectively for a very long time. Even though people have been formally studying communication for a long time, it is still necessary to continue studying communication in order to improve.

We recognize that there are countless good definitions of communication, but we feel it’s important to provide you with our definition so that you understand how we approach each chapter in this book. We are not arguing that this definition of communication is the only one you should consider viable, but you will understand the content of this text better if you understand how we have come to define communication. For the purpose of this text, we define communication as the process of using symbols to exchange meaning.

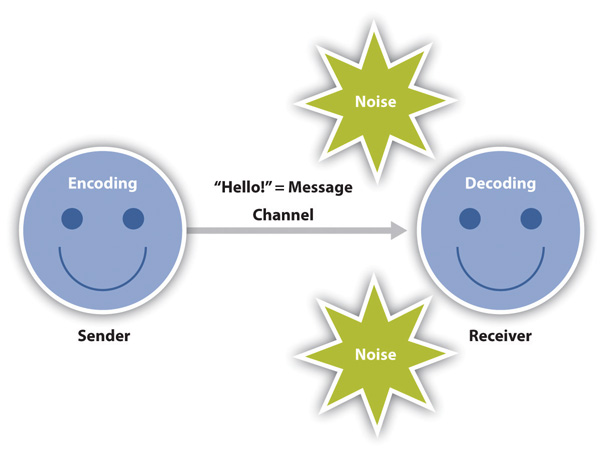

Let’s examine two models of communication to help you further grasp this definition. Shannon and Weaver (1946) proposed a Mathematical Model of Communication (often called the Linear Model) that serves as a basic model of communication. This model suggests that communication is simply the transmission of a message from one source to another. Watching YouTube videos serves as an example of this. You act as the receiver when you watch videos, receiving messages from the source (the YouTube video). To better understand this, let’s break down each part of this model. The Linear Model suggests communication moves only in one direction. The Sender encodes a Message, then uses a certain Channel (verbal/nonverbal communication) to send it to a Receiver who decodes (interprets) the message. Noise is anything that interferes with, or changes, the original encoded message.

- A sender is someone who encodes and sends a message to a receiver through a particular channel. The sender is the initiator of the communication. For example, when you text a friend, ask a teacher a question, or wave to someone you are the sender of a message.

- A receiver is the recipient of a message. Receivers must decode (interpret) messages in ways that are meaningful for them. For example, if you see your friend make eye contact, smile, wave, and say “hello” as you pass, you are receiving a message intended for you. When this happens you must decode the verbal and nonverbal communication in ways that are meaningful to you.

A message is the particular meaning or content the sender wishes the receiver to understand. The message can be intentional or unintentional, written or spoken, verbal or nonverbal, or any combination of these. For example, as you walk across campus you may see a friend walking toward you. When you make eye contact, wave, smile, and say “hello,” you are offering a message that is intentional, spoken, verbal and nonverbal.

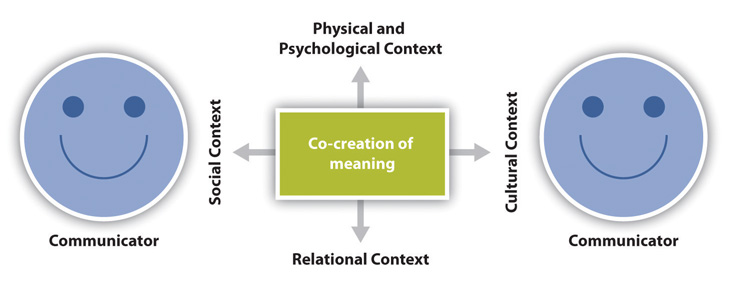

A major criticism of the Linear Model of Communication is that it suggests communication only occurs in one direction. It also does not show how context, or our personal experiences, impact communication. Television serves as a good example of the linear model. Have you ever talked back to your television while you were watching it? Maybe you were watching a sporting event or a dramatic show and you talked at the people on the television. Did they respond to you? We’re sure they did not. Television works in one direction. No matter how much you talk to the television it will not respond to you. Now apply this idea to the communication in your relationships. It seems ridiculous to think that this is how we would communicate with each other on a regular basis. This example shows the limits of the linear model for understanding communication, particularly human to human communication.Given the limitations of the Linear Model, Barnlund (1970) adapted the model to more fully represent what occurs in most human communication exchanges. The Transactional Model demonstrates that communication participants act as senders and receivers simultaneously, creating reality through their interactions. Communication is not a simple one-way transmission of a message: The personal filters and experiences of the participants impact each communication exchange. The Transactional Model demonstrates that we are simultaneously senders and receivers and that noise and personal filters always influence the outcomes of every communication exchange.

The ability for both parties to provide a response or return in the process is known as feedback or verbal or nonverbal messages sent during the communication process of decoding. Additionally, it suggests that meaning is co-constructed between all parties involved in any given communication interaction. This notion of co-constructed meaning is drawn from the relational, social, and cultural contexts that make up our communication environments. Personal and professional relationships, for example, have a history of prior interaction that informs present and future interactions. Social norms, or rules for behavior and interaction, greatly influence how we relate to one another. For example, if your professor taught the class while sitting down rather than standing up, you and your colleagues would feel awkward because that is not an expected norm for behavior in a classroom setting. How we negotiate cultural values, beliefs, attitudes, and traditions also impact our communication interactions. We may both be from Chicago, but our attitudes may differ greatly depending upon the neighborhood we grew up in.

While these models are overly simplistic representations of communication, they illustrate some of the complexities of defining and studying communication. Going back to Smith, Lasswell, and Casey, as Communication scholars we may choose to focus on one, all, or a combination of the following: senders of communication, receivers of communication, channels of communication, messages, noise, context, and/or the outcome of communication. Hopefully, you recognize that studying communication is simultaneously detail-oriented (looking at small parts of human communication), and far-reaching (examining a broad range of communication exchanges).

Perception and Identity

Have you ever considered the role that perception plays in how we communicate? Indeed, perception affects how we encode and decode messages and it may even impact how we act toward others. You may think of perception happening instantaneously. However, consider instead that perception is a three step process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting stimuli.

Think of stimuli as everything we might notice (see, hear, touch, taste, smell) in our environment, as well as others’ messages to us and our own feelings and thoughts. We simply cannot attend to everything (all the stimuli) in our environments and interactions. We, therefore, select certain stimuli, but not all. What factors impact how we select stimuli? Why do we watch one commercial, but ignore the others? If you close your eyes, can you recall the color shirt your instructor is wearing, whether your classroom has carpet or tiles, how many students are present, or advertisements tacked onto the classroom’s billboard? One reason we notice certain stimuli and not others is selective attention, the capacity for or process of reacting to certain stimuli selectively when several occur simultaneously. Clearly, it is less important what color the walls are painted in your classroom than the information your instructor wants you to hear and retain. What other reasons do we select certain stimuli and not others?

After selecting stimuli from our environment, we engage in organization. Perceptual organization is grouping visual stimuli into a pattern that is familiar to us, placing things, even people, into categories. You differentiate between friends, family, and work colleagues. However, you may also have friends you consider “family,” or colleagues who become friends. What criteria for a friend, family, or colleague do we have that allows for these shifts from one category to another? Additionally, we often compare new experiences with prior ones, or a new dating partner with an ideal archetype we have for the “perfect” romantic partner. What do we look for in a romantic partner, and from where do we inherit this criterion? It is important that we reflect upon how we organize experience and categorize others.

The final step in the process of perception is an interpretation or the assigning of meaning to what we have selected and organized. When we think of perception as something that “just happens” we are likely thinking of the interpreting step. However, as you can see, this is merely one step in a much more complex process. It is important that as communicators we be more intentional in the selection of stimuli and more reflective in how we organize experience. How might societal values, personal attitudes, cultural heritage, or beliefs affect the way we assign meaning in this context? Have you ever adjusted your opinion of someone or an experience after the initial impression? If so, what role did perception play in that adjustment? Being more aware of perception as a process is one way we can improve our communication skills.

No discussion of perception is complete without considering how personal identity affects the communication process. Indeed, how we see ourselves is often the starting point for how we relate to others. Identity, or our sense of self, includes both self-concept and self-esteem. Our self-concept is the sum total of who we think we are, or how we define ourselves. How many different categories or aspects of your self can you determine – familial (mother, daughter, sister), physical, emotional, romantic, civic, etc.? Comparatively, our self-esteem is the degree to which we value or devalue who we think we are. Consider those same categories that you determined for understanding your self-concept. Likely, you are more or less confident in some ways than others. Additionally, our self-esteem may change over time. Athletes spend decades training and competing in peak condition. However, as athletes age, they can no longer compete on the same level. This physical change may negatively impact their self-esteem. It is important to understand the power we have in how we choose to define and value ourselves, even over time as our lives evolve.

Personal identity is also characterized by how we manage our own communication behaviors and actions. We engage in identity management or managing others impressions by using communication strategies to influence how others see us. We will alter and adapt our behavior and/ or appearance accordingly to present the image or person we want to be seen as. Part of this is engaging in facework, strategies used to shape one’s image. If you think about your daily interactions and the different types of ways you strategize your communication flexibility in different communication contexts, you are thinking about facework. Competence in identity management involves the ability to competently apply facework. The different “faces” that you present best meet the relational, social, and cultural contexts of the situation. For example, your “face” that you present at work is more professional than that that you present to friends. In the workplace, you may attend to your dress, your posture, and even your tone of voice. You are also managing your impression and engaging in facework when you are presenting an online presence and determining how to present on different social media sites.

The following list includes additional factors that influence how we assign meaning to ourselves and others. Can you think of how one or more of these has impacted you or your relationship with others?

- Self-fulfilling Prophecy: When our behavior serves to fulfill someone else’s expectations for us.

- Attribution: The tendency to either take ownership of our behavior or performance or to blame others or outside forces.

- Stereotypes: Broad generalizations.

- Reflective Appraisal: Evaluating ourselves based upon how we see others seeing us.

With a clearer definition of communication and how it works, you are ready to learn about the history of communication and use your new perception skills to think about how communication has affected the landscape of communication discourse, education, and culture.