Chapter 2: Global Engagement and Culture

2.4 Conflict Management in Today’s Global Society

Introduction

This chapter will help you understand how conflict management can provide better communication for you within the university setting and in your professional and personal life. This chapter, written specifically for Indiana State University students, has been developed by the Department of Communication and the Office of Student Conduct and Integrity to help reduce stress brought on by limited or under-developed conflict management skills. After completing this chapter, each student should be able to understand their conflict style, strategies, and resources to navigate conflicts and help others around them better manage conflict with proactive and productive results. Remember, not all conflict can be resolved; but, with improved skill-sets, we should be able to manage them better.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the reasons for conflict.

- Identify strategies for resolving conflict.

- Explain the types of conflict.

- Identify styles of conflict management.

- Understand the role of attitude and behavior in conflict.

- Understand how culture influences conflict.

According to The Blackwell Dictionary of Sociology: A User’s Guide to Sociological Language, conflict is defined as (Johnson, 2000):

con·flict

Definition(s):noun:

a serious disagreement or argument, typically a protracted one: the eternal conflict between the sexes.

(i) a prolonged armed struggle.

(ii) an incompatibility between two or more opinions, principles, or interests.

(iii) Psychol. a condition in which a person experiences a clash of opposing wishes or needs.verb:

be incompatible or at variance; clash.

(i) [as adj.] (conflicted) having or showing confused and mutually inconsistent feelings.

– origin ME: from L.conflict-‘struck together,’ from v. confligere, from con-‘together’ + fligere ‘to strike.’

From this definition, one can surmise “conflict” traditionally involves incompatible needs or opinions. On a macro-level, nations battle over resources (jobs, land, oil, water, power, etc.) from sanctions to war. Failure to communicate may bring on stagnation (gridlock/standoff) or all out conflict. On a micro-level, individuals can find success by utilizing skills to helping find resolutions that are proactive, versus reactive, in nature.

Facilitating Discussions about Intercultural Communication Issues

Perhaps you may have noticed the theme of inequality as we have discussed topics such as unequal access to resources and benefits, racial discrimination, and racism. You may have also thought, “Oh, my, this is going to be a touchy chapter to read and discuss in class” or “this is interesting and relevant, but I feel uncomfortable talking about this as I don’t want to offend anyone.” These are very common and understandable reactions and ones we hear when we teach this subject matter. Hopefully, your instructor has set up a safe, open, and respectful classroom environment to facilitate such discussions. The fact that you are self-reflective of your feelings and how to express them to others is a great start! We too want you to be able to discuss this material both in and out of your class in a productive and self-reflective manner. To facilitate that goal we have included some additional concepts— privilege, ethnocentrism, and political correctness—that are useful when considering your own cultural identity, your place in society, and your communication with others.

Ethnocentrism

One of the first steps to communicating sensitively and productively about cultural identity is to be able to name and recognize one’s identity and the relative privilege that it affords. Similarly important, is a recognition that one’s cultural standpoint is not everyone’s standpoint. Our views of the world, what we consider right and wrong, normal or weird, are largely influenced by our cultural position or standpoint: the intersections of all aspects of our identity. One common mistake that people from all cultures are guilty of is ethnocentrism—placing one’s own culture and the corresponding beliefs, values, and behaviors in the center. When we do this, we view our position as normal and right and evaluate all other cultural systems against our own.

Ethnocentrism shows up in small and large ways: the WWII Nazi’s elevation of the Aryan race and the corresponding killing of Jews, Gypsies, gays and lesbians, and other known Aryan groups is one of the most horrific ethnocentric acts in history. However, ethnocentrism shows up in small and seemingly unconscious ways as well. In American culture, if you decided to serve dog meat as appetizers at your cocktail party you would probably disgust your guests and the police might even arrest you because the consumption of dog meat is not culturally acceptable. However, in China “it is neither rare nor unusual” to consume dog meat (Wingfield-Hayes, 2002). In the Czech Republic, the traditional Christmas dinner is carp and potato salad. Imagine how your U.S. family might react if you told them you were serving carp and potato salad for Christmas. In the Czech Republic, it is a beautiful tradition, but in America, it might not receive a warm welcome. Our cultural background influences every aspect of our lives from the food we consume to classroom curriculum. Ethnocentrism may show up in Literature classes, for example, as cultural bias dictates which “great works” students are going to read and study. More often than not, these works represent the given culture (i.e., reading French authors in France and Korean authors in Korea). This ethnocentric bias has received some challenge in United States’ schools, as teachers make efforts to create a multicultural classroom by incorporating books, short stories, and traditions from non-dominant groups. In the field of geography, there has been an ongoing debate about the use of a Mercator map versus a Peter’s Projection map. The arguments reveal cultural biases toward the Northern, industrialized nations.

Case In Point: The Greenland Problem

The Mercator projection creates increasing distortions of size as you move away from the equator. As you get closer to the poles the distortion becomes severe. Cartographers refer to the inability to compare size on a Mercator projection as “the Greenland Problem.” Greenland appears to be the same size as Africa, yet Africa’s land mass is actually fourteen times larger. Because the Mercator distorts size so much at the poles it is common to crop Antarctica off the map. This practice results in the Northern Hemisphere appearing much larger than it really is. Typically, the cropping technique results in a map showing the equator about 60% of the way down the map, diminishing the size and importance of the developing countries.Greenland is 0.8 million sq. miles and Africa is 11.6 million sq. miles, yet they often look roughly the same size on maps.

This was convenient, psychologically and practically, through the eras of colonial domination when most of the world powers were European. It suited them to maintain an image of the world with Europe at the center and looking much larger than it really was. Was this conscious or deliberate? Probably not, as most map users probably never realized the Eurocentric bias inherent in their world view. When there are so many other projections to choose from, why is it that today the Mercator projection is still such a widely recognized image used to represent the globe? The answer may be simply convention or habit. The inertia of habit is a powerful force.

Conflict Types, Styles, and Effects

Types of Conflict

Of the many reasons for conflict, there are three main types of conflict: simple, pseudo, and ego.

Simple Conflict: traditionally stems from different standpoints, views, or goals. With simple conflict, you may feel misunderstood, rejected, or isolated. Accepting another’s viewpoints and needs can solve the conflict, manage the situation, or allow the other person to feel valued. Not everyone has the same upbringing or experiences as you, so they may view the world in a different manner.

For this example of simple conflict, one might try being proactive and suggest another restaurant, which you both enjoy, and the two of you have a wonderful lunch together.

Pseudo Conflict: (pseudo, meaning “fake” or “false”) is a misunderstanding in communication. Either one or both have failed to comprehend what the other was attempting to convey. Left unchecked, this type of communication may further feelings of frustrations and misunderstanding.

Neither side took into consideration the time-difference, there was a conflict due to a misunderstanding. Thankfully you have a positive frame of mind and immediately send an e-mail explaining the misunderstanding and welcoming a second chance at that great position.

Ego Conflict: includes personal attacks and degrading of others. When this occurs, it is best to shift ego conflict to pseudo or simple conflict. Ego conflict may raise one’s blood pressure and pulse rates and spawn emotional outburst and physical violence.

With ego conflict, many times those involved may need to separate from the situation, even if for ten minutes or a day. During this time, each person should identify what the triggers were, how the confrontation could be better handled, and possible solutions. Each should keep an open mind and focus on listening to the other person.

Conflict Styles

Conflict Resolution Assessment

Take the assessment developed by the University of Arizona. What conflict resolution style do you follow?

Note that based on the best available research in the field, this questionnaire is designed to assist the user in understanding and assessing his/her current performance. The author makes no implied guarantee of its accuracy or the limits of its applicability.

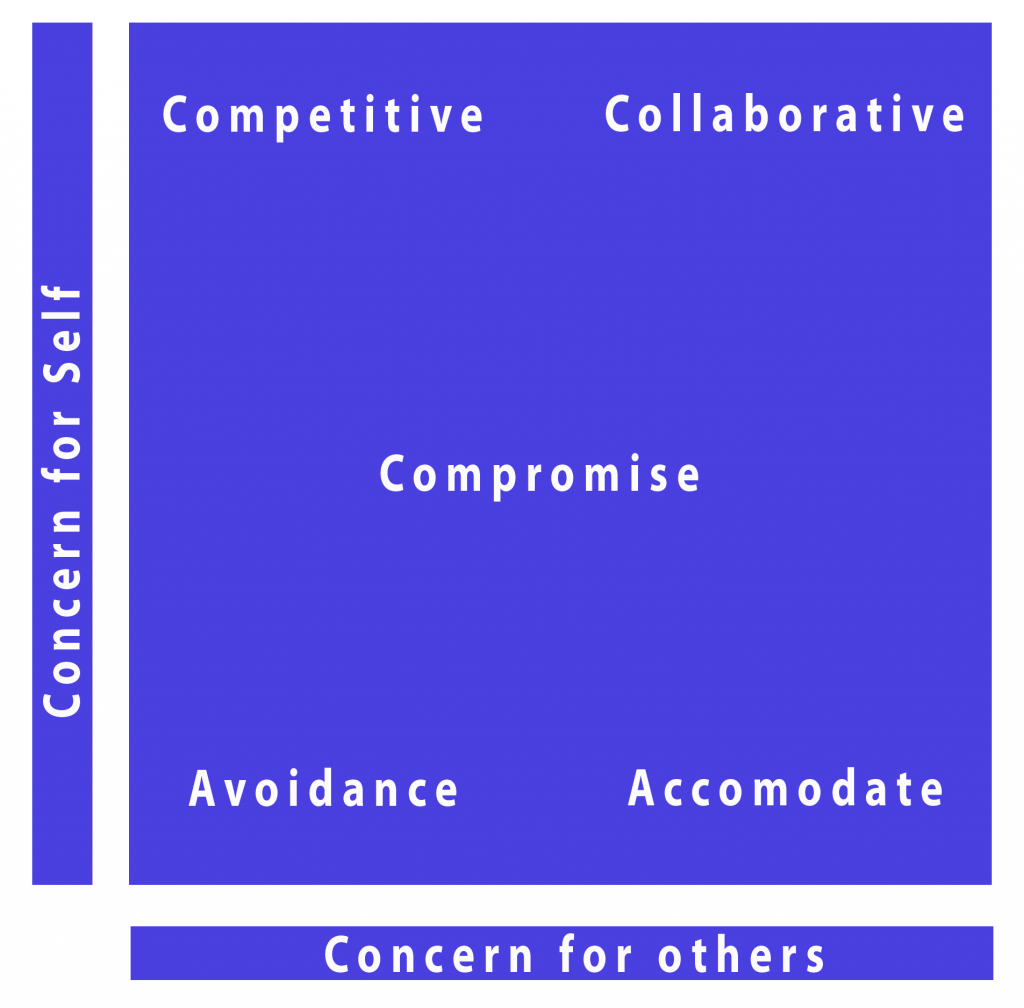

There are five types of conflict styles: avoidance, accommodation, collaboration, competition, and compromise. Each of us has a conflict style that pairs with our personality and our values, beliefs, and experiences. It is possible to have more than one style and the difference of where those styles are more viable can depend on the environment of the conflict.

Let’s review the different types of conflict strategies and then discuss why Susan responds differently in her work at home life.

The graph above (adapted from Moore, The Mediation Process) shows how higher/lower concern for self and others affects how we manage conflict. High concern for self may include our desire to control others whereas, low concern for self, sees one hiding from the conflict altogether. With high concern for others, one may seek to work together, or with low concern for others seek to give in to demands or needs. Compromise occupies a middle ground, where many may feel they did not get everything they wanted or needed.

Avoidance: “Conflict? What Conflict?”

Strategies of this style include denial, ignoring, and withdrawing. With limited concern for yourself and sometimes others, an individual with this style will avoid addressing any conflicts or issues. One is not committed to standing their ground or that of others. In this case, the person does not feel they get what they want or need and others feel the same. This is seen as a lose-lose approach where both sides never manage or address what causes their conflict. Both may feel unfulfilled or ignored.

Competition: “My way is the only way.”

In contrast to “avoidance,” a competitive style wants to win at any cost with the competitive style. Strategies of this style would include controlling, arguing, outsmarting, and contending. One has high concern for self and little to no concern for others. This style may have one seen as demanding or selfish. Making a stance, when needed, may be warranted; however, if this is a common conflict style, others will feel they are being bullied. This is seen as a win-lose approach to conflict. With this approach, one wins- usually at the expense of the other person. This has the loser feeling short-changed or that needs are being ignored.

Accommodation: “Whatever you want is okay with me.”

Strategies to this style include appeasement, agreement, and flattery. Those with accommodation conflict styles have a higher concern for others and less of self. Here, they give into other’s needs and demands and sacrifice their own needs. If chronically using this form of conflict management, others may take advantage of this person. Accommodating individuals will feel they are being taken advantage of and never have their own needs fulfilled.

Collaboration: “Let’s solve this problem together!”

With this type of conflict style, individuals come up with a variety of solutions and the one was chosen is one favored by both. Strategies for this style would include gathering information, looking for other options, conversation, and agreeing to disagree. Referring back to the restaurant scenario, in this style, individuals choose a restaurant both accept. For example, Jane and Thomas are going out for lunch. Jane, a semi-vegetarian, wants seafood and Thomas, a die hard red meat eater, is craving steak. To collaborate, the two throw out other options and decide to go to an Italian restaurant, instead. Both love Italian food and are happy to give up their initial choice. This win-win approach makes both feel a balanced solution was reached for both sides to feel satisfied.

Compromise: “Meet me in the middle.”

Strategies for this style of conflict include reducing expectations, negotiating, a little something for all involved. Compromise is keeping others and ones’ own needs into consideration. This may have you give up what you want today- in exchange for another day. Each works for success and happiness. This type is great if used over time and works well with long-term relationships. A good example is two friends agreeing to go to the other’s choice for lunch and the next time going to the second person’s choice. Both get what they want; but, must wait until it is their turn.

Small Group Discussion

Discuss whether you agree or disagree with your assigned conflict style. Were there other styles you were close to? If yes, which ones and discuss how you think the two relate to one another. Are there pieces of the definitions of the strategies you disagree with if so, share why. Also, think back to Susan and how she has different conflict styles in different environments. Why do you think this is?

Thinking About Conflict

When you hear the word “conflict,” do you have a positive or negative reaction? Are you someone who thinks conflict should be avoided at all costs? While conflict may be uncomfortable and challenging it does not have to be negative. Conflict is a natural part of life. Conflict can bring a sense of stress, anxiety, frustration, feeling overwhelmed, emotional; however, conflict can also be rewarding, educational, rewarding, collaborative, and foster positive change internally and external relationships. Most often conflicts can be resolved when both parties feel they have “won” and without the need for someone to “lose.”

Think about the social and political changes that came about from the conflict of the civil rights movement during the 1960’s. There is no doubt that this conflict was painful and even deadly for some civil rights activists, but the conflict resulted in the elimination of many discriminatory practices and helped create a more egalitarian social system in the United States. Let’s look at two distinct orientations to conflict, as well as options for how to respond to conflict in our interpersonal relationships.

Conflict as Destructive

When we shy away from conflict in our interpersonal relationships we may do so because we conceptualize it as destructive to our relationships. As with many of our beliefs and attitudes, they are not always well-grounded and lead to destructive behaviors. Augsburger outlined four assumptions of viewing conflict as destructive.

- Conflict is a destructive disturbance of the peace.

- The social system should not be adjusted to meet the needs of members; rather, members should adapt to the established values.

- Confrontations are destructive and ineffective.

- Disputants should be punished.

When we view conflict this way, we believe that it is a threat to the established order of the relationship.

Think about sports as an analogy of how we view conflict as destructive. In the U.S. we like sports that have winners and losers. Sports and games where a tie is an option often seem confusing to us. How can neither team win or lose? When we apply this to our relationships, it’s understandable why we would be resistant to engaging in conflict. “I don’t want to lose, and I don’t want to see my relational partner lose.” So, an option is to avoid conflict so that neither person has to face that result.

Conflict as Productive

In contrast to seeing conflict as destructive, we can view conflict as a productive, natural outgrowth and component of human relationships. Augsburger described four assumptions of viewing conflict as productive. 1. Conflict is a normal, useful process. 2. All issues are subject to change through negotiation. 3. Direct confrontation and conciliation are valued. 4. Conflict is a necessary renegotiation of an implied contract—a redistribution of opportunity, a release of tensions, and renewal of relationships.

From this perspective, conflict provides an opportunity for strengthening relationships, not harming them. Conflict is a chance for relational partners to find ways to meet the needs of one another, even when these needs conflict. Think back to our discussion of dialectical tensions. While you may not explicitly argue with your relational partners about these tensions, the fact that you are negotiating points to your ability to use conflict in productive ways for the relationship as a whole and the needs of the individuals in the relationship.

Generally, individuals respond to conflict in one of three ways:

- Ignore/Avoid. Pretending the conflict either does not exist or choosing to not confront the conflict/issue. The concern with ignoring/avoiding is it likely can become an internal conflict creating stress and anxiety. The longer the conflict sits un-addressed, the more frustration, resentment, and anger one build up inside.

- Physical/Verbal Altercation. Addressing the conflict through yelling and screaming, often with name-calling and variations of hate slurs, intimidating and threatening behaviors or baiting one another into a physical altercation. When the conflict becomes physical, both parties can find themselves in trouble with law enforcement and/or the university.

- Conflict Resolution. Addressing the conflict effectively and efficiently using one of the Conflict Resolution Methods described below.

Conflict Resolution Methods

Navigating conflict takes knowing and understanding your conflict style, being aware of your P.I.N. (positions, interests, and needs), and having the ability to articulate those to the person(s) whom you are experiencing conflict with. It is a best practice to seek the assistance of a neutral third party to help you navigate your particular conflict. Schrage and Giacomini define seven methods of conflict resolution. Note, for this section, an administration is defined as the University.

- Conflict Coaching. Individuals seek advice and guidance from administration to address a conflict more effectively and independently.

- Facilitated Dialogue. Students access administration for facilitation services to engage a conversation to gain understanding or to manage a conflict. In a facilitated dialogue, parties maintain ownership of decisions concerning the conversation and any resolution of a conflict.

- Mediation. Students utilize administration to serve as a third party to coordinate a structured session aimed at resolving a conflict and/or construct a “go forward” or future narrative for the parties involved.

- Restorative Justice Practices. Through a diversion program or as an addition to the adjudication process, the administration provides a space and facilitation of services for students taking ownership for harmful behavior and those parties affected by the behavior to jointly construct an agreement to restore community.

- Shuttle Dialogue. Administration actively negotiates an agreement between two parties that do not wish to directly engage with one another. This method may be an alternative to a formal adjudication (see below) process or part of the process associated with the Code of Student Conduct.

- Adjudication (Informal and Formal). Process organized through the conduct processes, often involving an arbitrator.

- Social Justice. Addresses the differences among us such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and etc.; while also valuing cultural differences and learning how to communicate within and across these differences. What separates social justice from diversity and multiculturalism is how social justice explicitly examines the power structures in society related to these differences as these power structures often result in privilege and oppression

Triggers and Self-monitoring Enhancement

Unfortunately, none of us have Super Hero powers. We are all simply human. We may stumble on triggers that make us more susceptible to managing conflict in a reactive or negative manner. Knowing your triggers can help reduce bad conflict and redirect to simple good conflict. Below are examples of common triggers that make us more vulnerable to poor conflict outcomes.

- Lack of sleep. When functioning on limited sleep, we become more irritable and likely to over-react to situations.

- Low blood sugar or lack of food. Because our blood sugar levels are lower, our bodies are having to work harder to maintain systems.

- Too hot/cold temperatures. Yes, environment plays a major role in our behavior. Some may experience irritable states when they become too warm or cold. This also includes other sensory triggers: too much noise, overwhelming smells, too many people around, etc.

- Limited information or not being able to understand information. Perhaps not understanding the vocabulary being used or the accent of the person makes you uncomfortable and more irritable.

- High face-saving. Some cultures see their public image as very important. If they feel disgraced or embarrassed they may become irate.

Understanding your triggers helps monitor yourself/actions in conflict situations and can enhance your reactions in a positive manner. By framing your conflict in a positive direction, knowing when you are emotional, what your triggers are (what sets you off), and seeking out proactive solutions, you can know how to handle conflict.

In conflicts, each person (or group) involved has a PIN: a position, an interest, and a need. PINs often help those working to find a resolution to the conflict because PINs develop into communication channels when determining the similarities and differences between the parties. Being aware of your own PINs and paying attention to the PIN of whom your conflict is with can be helpful.

- Positions. What we state we want

- Interests. What we really want

- Needs. What we must have

Outstanding Oranges Activity:

Divide into two large groups. Each group will be given additional information and should select one person to represent their offer to Farmer Johnston.

Farmer Johnston grows and sells oranges. His oranges are the best in the country. Two buyers approach Farmer Johnston and both want to buy the entire crop.

You represent the buyers and your objective is to present a PIN offer that the farmer cannot refuse.

“By understanding the various complexities that surround conflict, we are able to see the individual components for their actual value, rather than the negative feelings and terms that we have previously associated with this fact,” (Olshack, 2001).

Good, Bad, and Neutral Conflict

Research suggests individuals generally pre-select how they will react to conflict situations (Tamir, 2012). This pre-selection was dependent on desired and self- centered outcomes. (Kleiman & Hassin, 2013). With this being said, some individuals may be preparing themselves for poor or negative outcomes. By handling conflict in a logical manner, issues and situations can be good.

Good conflictbrings underlying issues and problems into focus. When handled well, conflict can improve relationships and quality of life. Individuals should consider when and where they will bring up conflict issues and if in an emotional state, consider postponing discussion until a later time. This conversation should be objective and not include personal attacks or bias. Suggestions for solutions should be solicited from both sides and include unique or different recommendations for change. These suggestions should be received openly and without bias. Each person should identify the underlying issues for the conflict and determine solutions acceptable to all parties.

Bad conflictbrings issues to light in a negative manner. Individuals make personal attacks and are not able to accept responsibility for any part of the conflict. Furthermore, they see conflict as bad and personal. Emotions over run the conflict and solutions for improvement are limited or none existent. With bad conflict, individuals may be quick to judge and run with their emotions.

Neutral conflictmay postpone or table conflict for an indefinite period of time. It may also bring in a third party, or arbitrator, to negotiate a solution that is balanced for all. Sometimes, timing is critical to delivering a positive outcome in the conflict. Conflict is seen as positive and brings about change in a balanced manner.

Strategies for Handling and Preventing Conflict

There are a variety of approaches or styles to managing conflict, especially when emotionally charged, that individuals may use (Blake & Mouton, 1994). Culture, or an individual’s upbringing, usually reflects how one manages such conflict (Croucher, Bruno, McGrath, et al, 2012). Knowing how to identify your own conflict styles, needs, and others needs will help you to develop better, more rewarding, outcomes and demonstrate an ethical perspective.

When individuals compete for resources, like competing for a new job or office space, there is a waste of time, money, or attention from others. There may be incompatible or interference in reaching goals (Hocker & Wilmot, 1991). This may be a conflict on where to go to college, what to eat for dinner, using cell phones in class, or too much noise in the dorm. In addition, research shows that those from different cultures, with differing high or low context approaches to communication, may have varied conflict management styles that further add to the management of conflict (Croucher, Bruno, McGrath, et al, 2012).

In addition to context, our social norms and rituals may create expectations that may trigger conflict. Norms are expected behaviors we abide by within groups. These may include our dress, interaction with authorities and elders, social roles (feminine/masculine, parent/child, leader/follower), and verbal/nonverbal communication. By being too loud at a restaurant, disclosing too much personal information, or questioning authority, one might trigger conflict.

Rituals, intentional rituals, and natural rituals may also cause conflict. Intentional rituals, like observing a national holiday or attending a religious service, may conflict with someone else’s standpoint, an attitude to or outlook on issues, typically arising from one’s circumstances or beliefs. Natural rituals, such as putting dishes in the dishwasher, flushing the toilet after using, and affect the moods and emotions of others (Goffman, 1967).

Emotions and our Developing Brain

Though often overlooked, when discussing “conflict” extreme reactions of emotional response can be profound and cause individuals who have not learned to manage conflict proactively and productively to react in a destructive manner (Lindner, 2009). The brain is hardwired to react to conflict. This includes emotional processing through six brain structures (amygdala, basal, ganglia, left prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and orbital frontal cortex). It is the last subsystem, orbital frontal, where individuals are able to regulate control over emotions. Delayed biological development, brain injury, and social environmental factors may lead to less favorable management of conflict (Lindner, 2009).

As an adolescence’s body develops, the frontal lobe further develops and reasoning draws within the more logical and less emotional responding. The individual is, thus, better able to understand social norms expected for an adult. Learning to proactively manage conflict re-enforces successful conflict management, ethical behavior, or collaboration. Individuals may feel more at peace.

Behavioral Expectations

Earlier, we discussed Triggers and Self-Monitoring, as well as the PIN Model. Knowing yourself and taking the time to get to know others is a proactive approach to being able to address conflicts as they arise. Communities, teams, staffs, roommates, and classrooms, should create group expectations and goals in order to establish a community or common standard.

Indiana State University has the Sycamore Standard and the Code of Student Conduct. These documents serve as Behavioral Expectations where conflicts can be addressed using the expectations as a guide for resolution.

Conflict management is a uniquely Communication-oriented skill, and it is likely that before this class you had not been exposed to the many ways we can understand and resolve conflict in our relationships. Successfully completing a college degree includes how well you manage conflict with your classmates, teachers, family and friends back home, and many other relationships. As a student at Indiana State University, you are encouraged to draw upon the many resources available to you for help in managing conflict.

It is important to recognize the types of conflicts we encounter on a daily basis, as well as the various strategies or styles for approaching conflict situations. Employers are increasingly seeking applicants who can demonstrate emotional intelligence, which includes an acumen for managing conflict effectively in professional settings. Additionally, it is important to appreciate the positive or generative possibilities of conflict. If you think about out it, some of the best ideas produced by a culture — like the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, or most intimate bonds between family and friends — are forged out of conflict situations. If we commit to conflict management as a life-long learning experience, rather than something to fear, then our personal, professional, and public lives will benefit greatly.