Chapter 7: Types of Interpersonal Relatonships

7.3 Communication & Romantic Relationships

Romance has swept humans off their feet for hundreds of years, as is evidenced by countless odes written by love-struck poets, romance novels, and reality television shows like The Bachelor and The Bachelorette. Whether pining for love in the pages of a diary or trying to find a soul mate from a cast of suitors, love and romance can seem to take us over at times. As we have learned, communication is the primary means by which we communicate emotion, and it is how we form, maintain, and end our relationships. In this section, we will explore the communicative aspects of romantic relationships including relationship formation, stages of relationships, social networks, and cultural influences.

Relationship Formation

Much of the research on romantic relationships distinguishes between premarital and marital couples. However, given the changes in marriage and the diversification of recognized ways to couple, I will use the following distinctions: dating, cohabitating, and partnered couples. The category for dating couples encompasses the courtship period, which may range from a first date through several years. Once a couple moves in together, they fit into the category of cohabitating couple. Partnered couples take additional steps to verbally, ceremonially, or legally claim their intentions to be together in a long-term committed relationship. The romantic relationships people have before they become partnered provide important foundations for later relationships. But how do we choose our romantic partners, and what communication patterns affect how these relationships come together and apart? The following are commonly identified factors of attraction[1] (i.e., relationship formation influences):

- Physical attractiveness: In terms of attraction, over the past sixty years, men and women have more frequently reported that physical attraction is an important aspect of mate selection. But what characteristics lead to physical attraction? Despite the saying that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” there is much research that indicates body and facial symmetry are the universal basics of judging attractiveness. Further, the matching hypothesis states that people with similar levels of attractiveness will pair together despite the fact that people may idealize fitness models or celebrities who appear very attractive.[2] However, judgments of attractiveness are also communicative and not just physical. Other research has shown that verbal and nonverbal expressiveness are judged as attractive, meaning that a person’s ability to communicate in an engaging and dynamic way may be able to supplement for some lack of physical attractiveness.

- Similarities: In order for a relationship to be successful, the people in it must be able to function with each other on a day-to-day basis, once the initial attraction stage is over. Similarity in preferences for fun activities and hobbies like attending sports and cultural events, relaxation, television and movie tastes, and socializing were correlated to more loving and well-maintained relationships. Similarity in role preference means that couples agree whether one or the other or both of them should engage in activities like indoor and outdoor housekeeping, cooking, and handling the finances and shopping. Couples who were not similar in these areas reported more conflict in their relationship.[3]

- Complementarity: In addition to being drawn to people who share similar values, hobbies, and preferences, we are also attracted to individuals who bring strengths to a relationships that we dont possess. For example, a structured, organized individual and a free-spirited, spontaneous individual may be attracted to one another. The organized person may be drawn to the flexibility modeled by their free-spirited partner, and the fre- spirited partner may admire and be drawn towards developing more structure in their life.

- Competence: A forth factor of attraction has to do with the social competence of a potential partner. We are typically drawn to individuals who are skilled at interacting with a wide array of individual, and less incline to begin a relationship with someone who seems to violate typical social norms (e.g., being polite to a customer service employees).

- Rewards: We then to enter into relationships with others who add value to our lives (e.g., emotion support, entertainment, companionship) as opposed to those who detract from our lives. After relationships develop and mature, individuals may sustain periods of relational costs (e.g., financial strain based on partner’s loss of a job), but we typically dont start relationships that are costly

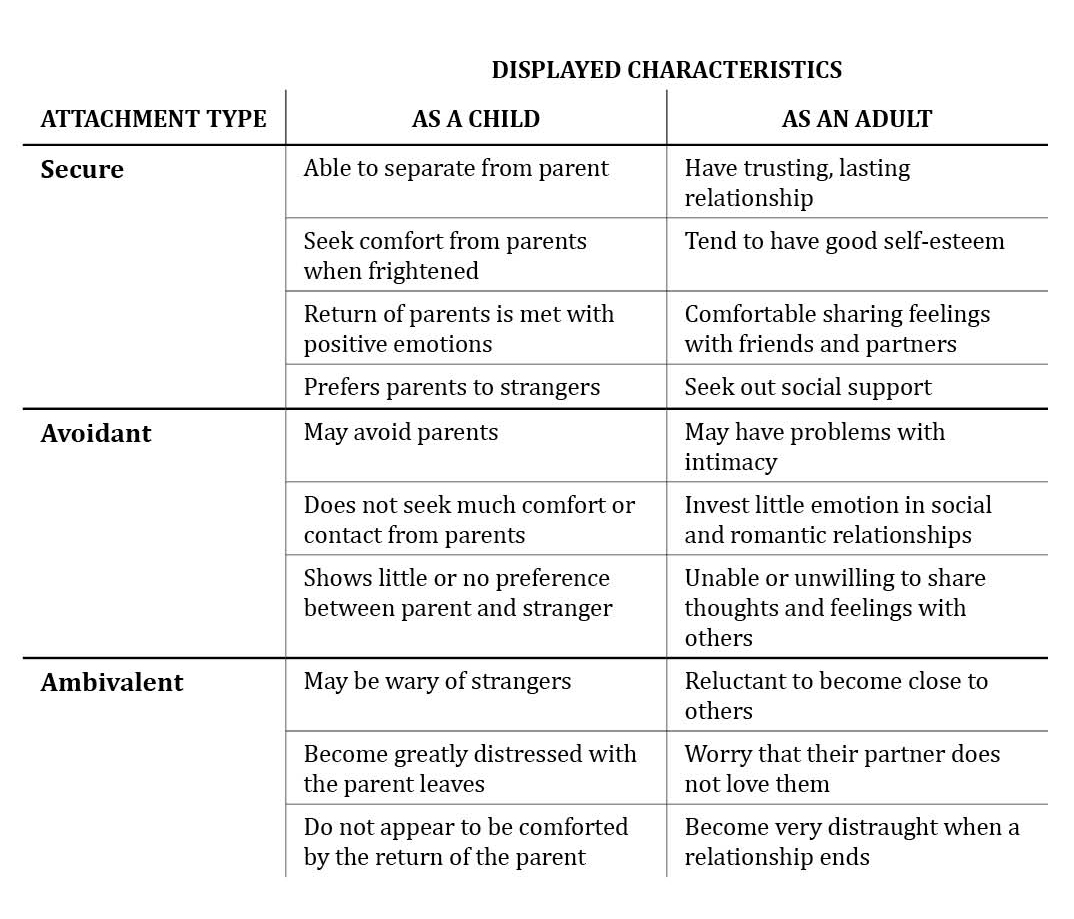

- Personal Attachment Style: Attachment theory relates to the bond that a child feels with their primary caregiver. Research has shown that the attachment style (secure, avoidant, ambivalent) formed as a child influences adult romantic relationships. These styles form expectations for later relationships, which can impact how and when we form relationships.

“Getting Critical”

Arranged Marriages

Although romantic love is considered a precursor to marriage in Western societies, this is not the case in other cultures. As was noted earlier, mutual attraction and love are the most important factors in mate selection in research conducted in the United States. In some other countries, like China, India, and Iran, mate selection is primarily decided by family members and may be based on the evaluation of a potential partner’s health, financial assets, social status, or family connections. In some cases, families make financial arrangements to ensure the marriage takes place. Research on marital satisfaction of people in autonomous (self-chosen) marriages and arranged marriages has been mixed, but a recent study found that there was no significant difference in marital satisfaction between individuals in marriages of choice in the United States and those in arranged marriages in India.[4] While many people undoubtedly question whether a person can be happy in an arranged marriage, in more collectivistic (group-oriented) societies, accommodating family wishes may be more important than individual preferences. Rather than love leading up to a marriage, love is expected to grow as partners learn more about each other and adjust to their new lives together once married.

- Do you think arranged marriages are ethical? Why or why not?

- Try to step back and view both types of marriages from an outsider’s perspective. The differences between the two types of marriage are fairly clear, but in what ways are marriages of choice and arranged marriages similar?

- List potential benefits and drawbacks of marriages of choice and arranged marriages.

- Love and Sexuality in Romantic Relationships

Stages of Relational Interaction

Communication is at the heart of forming our interpersonal relationships. We reach the achievement of relating through the everyday conversations and otherwise trivial interactions that form the fabric of our relationships. It is through our communication that we adapt to the dynamic nature of our relational worlds, given that relational partners do not enter each encounter or relationship with compatible expectations. Communication allows us to test and be tested by our potential and current relational partners. It is also through communication that we respond when someone violates or fails to meet those expectations.[5]

There are ten established stages of interaction that can help us understand how relationships come together and come apart.[6] We will discuss each stage in more detail, but in Table 7.1 “Relationship Stages” you will find a list of the communication stages. We should keep the following things in mind about this model of relationship development: relational partners do not always go through the stages sequentially, some relationships do not experience all the stages, we do not always consciously move between stages, and coming together and coming apart are not inherently good or bad. As we have already discussed, relationships are always changing—they are dynamic. Although this model has been applied most often to romantic relationships, most relationships follow a similar pattern that may be adapted to a particular context.

Table 7.3 Relationship Stages

| Process | Stage | Representative Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Coming Together | Initiating | “My name’s Rich. It’s nice to meet you.” |

| Experimenting | “I like to cook and refinish furniture in my spare time. What about you?” | |

| Intensifying | “I feel like we’ve gotten a lot closer over the past couple months.” | |

| Integrating | (To friend) “We just opened a joint bank account.” | |

| Bonding | “I can’t wait to tell my parents that we decided to get married!” | |

| Coming Apart | Differentiating | “I’d really like to be able to hang out with my friends sometimes.” |

| Circumscribing | “Don’t worry about problems I’m having at work. I can deal with it.” | |

| Stagnating | (To self) “I don’t know why I even asked him to go out to dinner. He never wants to go out and have a good time.” | |

| Avoiding | “I have a lot going on right now, so I probably won’t be home as much.” | |

| Terminating | “It’s important for us both to have some time apart. I know you’ll be fine.” |

Source: Adapted from Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 34.

Initiating

In the , people size each other up and try to present themselves favorably. Whether you run into someone in the hallway at school or in the produce section at the grocery store, you scan the person and consider any previous knowledge you have of them, expectations for the situation, and so on. Initiating is influenced by several factors.

If you encounter a stranger, you may say, “Hi, my name’s Rich.” If you encounter a person you already know, you’ve already gone through this before, so you may just say, “What’s up?” Time constraints also affect initiation. A quick passing calls for a quick hello, while a scheduled meeting may entail a more formal start. If you already know the person, the length of time that’s passed since your last encounter will affect your initiation. For example, if you see a friend from high school while home for winter break, you may set aside a long block of time to catch up; however, if you see someone at work that you just spoke to ten minutes earlier, you may skip initiating communication. The setting also affects how we initiate conversations, as we communicate differently at a crowded bar than we do on an airplane. Even with all this variation, people typically follow typical social scripts for interaction at this stage.

Experimenting

The scholars who developed these relational stages have likened the , where people exchange information and often move from strangers to acquaintances, to the “sniffing ritual” of animals.[7] A basic exchange of information is typical as the experimenting stage begins. For example, on the first day of class, you may chat with the person sitting beside you and take turns sharing your year in school, hometown, residence hall, and major. Then you may branch out and see if there are any common interests that emerge. Finding out you’re both St. Louis Cardinals fans could then lead to more conversation about baseball and other hobbies or interests; however, sometimes the experiment may fail. If your attempts at information exchange with another person during the experimenting stage are met with silence or hesitation, you may interpret their lack of communication as a sign that you shouldn’t pursue future interaction.

Experimenting continues in established relationships. Small talk, a hallmark of the experimenting stage, is common among young adults catching up with their parents when they return home for a visit or committed couples when they recount their day while preparing dinner. Small talk can be annoying sometimes, especially if you feel like you have to do it out of politeness. I have found, for example, that strangers sometimes feel the need to talk to me at the gym (even when I have ear buds in). Although I’d rather skip the small talk and just work out, I follow social norms of cheerfulness and politeness and engage in small talk. Small talk serves important functions, such as creating a communicative entry point that can lead people to uncover topics of conversation that go beyond the surface level, helping us audition someone to see if we’d like to talk to them further, and generally creating a sense of ease and community with others. And even though small talk isn’t viewed as very substantive, the authors of this model of relationships indicate that most of our relationships do not progress far beyond this point.[8]

Intensifying

As we enter the , we indicate that we would like or are open to more intimacy, and then we wait for a signal of acceptance before we attempt more intimacy. This incremental intensification of intimacy can occur over a period of weeks, months, or years and may involve inviting a new friend to join you at a party, then to your place for dinner, then to go on vacation with you. It would be seen as odd, even if the experimenting stage went well, to invite a person who you’re still getting to know on vacation with you without engaging in some less intimate interaction beforehand. In order to save face and avoid making ourselves overly vulnerable, steady progression is key in this stage. Aside from sharing more intense personal time, requests for and granting favors may also play into intensification of a relationship. For example, one friend helping the other prepare for a big party on their birthday can increase closeness. However, if one person asks for too many favors or fails to reciprocate favors granted, then the relationship can become unbalanced, which could result in a transition to another stage, such as differentiating.

Other signs of the intensifying stage include creation of nicknames, inside jokes, and personal idioms; increased use of we and our; increased communication about each other’s identities (e.g., “My friends all think you are really laid back and easy to get along with”); and a loosening of typical restrictions on possessions and personal space (e.g., you have a key to your best friend’s apartment and can hang out there if your roommate is getting on your nerves). Navigating the changing boundaries between individuals in this stage can be tricky, which can lead to conflict or uncertainty about the relationship’s future as new expectations for relationships develop. Successfully managing this increasing closeness can lead to relational integration.

Integrating

In the , two people’s identities and personalities merge, and a sense of interdependence develops. Even though this stage is most evident in romantic relationships, there are elements that appear in other relationship forms. Some verbal and nonverbal signals of the integrating stage are when the social networks of two people merge; those outside the relationship begin to refer to or treat the relational partners as if they were one person (e.g., always referring to them together—“Let’s invite Olaf and Bettina”); or the relational partners present themselves as one unit (e.g., both signing and sending one holiday card or opening a joint bank account). Even as two people integrate, they likely maintain some sense of self by spending time with friends and family separately, which helps balance their needs for independence and connection.

Bonding

The includes a public ritual that announces formal commitment. These types of rituals include weddings, commitment ceremonies, and civil unions. Obviously, this stage is almost exclusively applicable to romantic couples. In some ways, the bonding ritual is arbitrary, in that it can occur at any stage in a relationship. In fact, bonding rituals are often later annulled or reversed because a relationship doesn’t work out, perhaps because there wasn’t sufficient time spent in the experimenting or integrating phases. However, bonding warrants its own stage because the symbolic act of bonding can have very real effects on how two people communicate about and perceive their relationship. For example, the formality of the bond may lead the couple and those in their social network to more diligently maintain the relationship if conflict or stress threatens it.

Differentiating

Individual differences can present a challenge at any given stage in the relational interaction model; however, in the , communicating these differences becomes a primary focus. Differentiating is the reverse of integrating, as we and our reverts back to I and my. People may try to reboundary some of their life prior to the integrating of the current relationship, including other relationships or possessions. For example, Carrie may reclaim friends who became “shared” as she got closer to her roommate Julie and their social networks merged by saying, “I’m having my friends over to the apartment and would like to have privacy for the evening.” Differentiating may onset in a relationship that bonded before the individuals knew each other in enough depth and breadth. Even in relationships where the bonding stage is less likely to be experienced, such as a friendship, unpleasant discoveries about the other person’s past, personality, or values during the integrating or experimenting stage could lead a person to begin differentiating.

Circumscribing

To circumscribe means to draw a line around something or put a boundary around it.[9] So in the , communication decreases and certain areas or subjects become restricted as individuals verbally close themselves off from each other. They may say things like “I don’t want to talk about that anymore” or “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.” If one person was more interested in differentiating in the previous stage, or the desire to end the relationship is one-sided, verbal expressions of commitment may go unechoed—for example, when one person’s statement, “I know we’ve had some problems lately, but I still like being with you,” is met with silence. Passive-aggressive behavior and the demand-withdrawal conflict pattern, which we discussed in Chapter 6 “Interpersonal Communication Processes“, may occur more frequently in this stage. Once the increase in boundaries and decrease in communication becomes a pattern, the relationship further deteriorates toward stagnation.

Stagnating

During the , the relationship may come to a standstill, as individuals basically wait for the relationship to end. Outward communication may be avoided, but internal communication may be frequent. The relational conflict flaw of mindreading takes place as a person’s internal thoughts lead them to avoid communication. For example, a person may think, “There’s no need to bring this up again, because I know exactly how he’ll react!” This stage can be prolonged in some relationships. Parents and children who are estranged, couples who are separated and awaiting a divorce, or friends who want to end a relationship but don’t know how to do it may have extended periods of stagnation. Short periods of stagnation may occur right after a failed exchange in the experimental stage, where you may be in a situation that’s not easy to get out of, but the person is still there. Although most people don’t like to linger in this unpleasant stage, some may do so to avoid potential pain from termination, some may still hope to rekindle the spark that started the relationship, or some may enjoy leading their relational partner on.

Avoiding

Moving to the avoiding stage may be a way to end the awkwardness that comes with stagnation, as people signal that they want to close down the lines of communication. Communication in the avoiding stage can be very direct—“I don’t want to talk to you anymore”—or more indirect—“I have to meet someone in a little while, so I can’t talk long.” While physical avoidance such as leaving a room or requesting a schedule change at work may help clearly communicate the desire to terminate the relationship, we don’t always have that option. In a parent-child relationship, where the child is still dependent on the parent, or in a roommate situation, where a lease agreement prevents leaving, people may engage in cognitive dissociation, which means they mentally shut down and ignore the other person even though they are still physically present.

Terminating

The terminating stage of a relationship can occur shortly after initiation or after a ten- or twenty-year relational history has been established. Termination can result from outside circumstances such as geographic separation or internal factors such as changing values or personalities that lead to a weakening of the bond. Termination exchanges involve some typical communicative elements and may begin with a summary message that recaps the relationship and provides a reason for the termination (e.g., “We’ve had some ups and downs over our three years together, but I’m getting ready to go to college, and I either want to be with someone who is willing to support me, or I want to be free to explore who I am.”). The summary message may be followed by a distance message that further communicates the relational drift that has occurred (e.g., “We’ve really grown apart over the past year”), which may be followed by a disassociation message that prepares people to be apart by projecting what happens after the relationship ends (e.g., “I know you’ll do fine without me. You can use this time to explore your options and figure out if you want to go to college too or not.”). Finally, there is often a message regarding the possibility for future communication in the relationship (e.g., “I think it would be best if we don’t see each other for the first few months, but text me if you want to.”).[10] These ten stages of relational development provide insight into the complicated processes that affect relational formation and deterioration. We also make decisions about our relationships by weighing costs and rewards.

Relational Maintenance

When most of us think of romantic relationships, we think about love. However, love did not need to be a part of a relationship for it to lead to marriage until recently. In fact, marriages in some cultures are still arranged based on pedigree (family history) or potential gain in money or power for the couple’s families. Today, love often doesn’t lead directly to a partnership, given that most people don’t partner with their first love. Love, like all emotions, varies in intensity and is an important part of our interpersonal communication.

To better understand love, we can make a distinction between passionate love and companionate love.[11] Passionate love entails an emotionally charged engagement between two people that can be both exhilarating and painful. For example, the thrill of falling for someone can be exhilarating, but feelings of vulnerability or anxiety that the love may not be reciprocated can be painful. Companionate love is affection felt between two people whose lives are interdependent. For example, romantic partners may come to find a stable and consistent love in their shared time and activities together. The main idea behind this distinction is that relationships that are based primarily on passionate love will terminate unless the passion cools overtime into a more enduring and stable companionate love. This doesn’t mean that passion must completely die out for a relationship to be successful long term. In fact, a lack of passion could lead to boredom or dissatisfaction. Instead, many people enjoy the thrill of occasional passion in their relationship but may take solace in the security of a love that is more stable. While companionate love can also exist in close relationships with friends and family members, passionate love is often tied to sexuality present in romantic relationships. So how do relational partners maintain their relationship as the style of love ebbs and flows? The following are some relationship maintenance strategies:

- Social Networks: Social networks influence all our relationships but have gotten special attention in research on romantic relations. Romantic relationships are not separate from other interpersonal connections to friends and family. Is it better for a couple to share friends, have their own friends, or attempt a balance between the two? Overall, research shows that shared social networks are one of the strongest predictors of whether or not a relationship will continue or terminate.

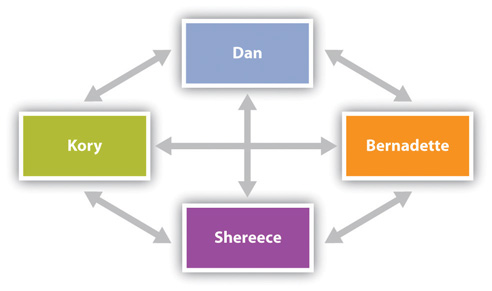

Network overlap refers to the number of shared associations, including friends and family, that a couple has.[12] For example, if Dan and Shereece are both close with Dan’s sister Bernadette, and all three of them are friends with Kory, then those relationships completely overlap (see Figure 7.3 “Social Network Overlap”).

Figure 7.3 Social Network Overlap

Network overlap creates some structural and interpersonal elements that affect relational outcomes. Friends and family who are invested in both relational partners may be more likely to support the couple when one or both parties need it. In general, having more points of connection to provide instrumental support through the granting of favors or emotional support in the form of empathetic listening and validation during times of conflict can help a couple manage common stressors of relationships that may otherwise lead a partnership to deteriorate.[13]

In addition to providing a supporting structure, shared associations can also help create and sustain a positive relational culture. For example, mutual friends of a couple may validate the relationship by discussing the partners as a “couple” or “pair” and communicate their approval of the relationship to the couple separately or together, which creates and maintains a connection.[14] Being in the company of mutual friends also creates positive feelings between the couple, as their attention is taken away from the mundane tasks of work and family life. Imagine Dan and Shereece host a board-game night with a few mutual friends in which Dan wows the crowd with charades, and Kory says to Shereece, “Wow, he’s really on tonight. It’s so fun to hang out with you two.” That comment may refocus attention onto the mutually attractive qualities of the pair and validate their continued interdependence.

2. Openness and Assurance: In additional to social networks, relational partners who talk about the nature of their relationship and share their personal needs and concerns are more likely to stay together. Not only does this type of talk ensure that relational problems dont fester to the point of a major conflict, the act of talking with one another is an indicator of commitment. Feeling assured that you and your partner are “in this together” and for the long haul, helps relationships sustain over time.

3. Shared Tasks: A final strategy relational partners use to sustain relationships is helping one another with life’s chores. Since relationships are embedded within networks of relationship and personal responsibilities, having a relational partner help with mundane (washing dishes) and significant (help with placement of elder parent in nursing home) life tasks is highly valued.

“Getting Plugged In”

Online Dating

It is becoming more common for people to initiate romantic relationships through the Internet, and online dating sites are big business, bringing in $470 million a year.[15] Whether it’s through sites like Match.com or OkCupid.com or through chat rooms or social networking, people are taking advantage of some of the conveniences of online dating. But what are the drawbacks?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of online dating?

- What advice would you give a friend who is considering using online dating to help him or her be a more competent communicator?

Relational Termination

Not all romantic relationships last forever. Sometimes the end of these relationships brings grief and sadness. At other times, relational partners may come to realize that the costs of being in relationship with one another outweigh the benefits, and thus feel a sense of relief and optimism when a relationship ends. Relational partners have a variety of termination strategies that may be used [16]

| Strategy | Tactic | Example |

| Positive Tone | Fairness, fatalism | “Its not right to keep you in this relationship when I know I’m not ready to commit”, “We both know this isnt working.” |

| De-escalation | Promise of friendship, Implied possible reconciliation | “We can still be friends”, “Who knows what the future holds; maybe time apart will make us realize we are meant to be” |

| Withdrawal | Avoiding contact with the other | “I’m not going to be able to go to your families this weekend” |

| Justification | Emphasize positive of disengaging or negative of staying together | “We should see other people since we’ve grown to wanting different things”, “We wont reach our personal goals if we stay together.” |

| Negative identity management | Non-negotiable | “I’m done” |

Key Takeaways

- Romantic relationships include dating, cohabitating, and partnered couples.

- There are a variety of factors of attraction that contribute to the start of romantic relationships.

- Romantic relationships can move through some identifiable stages.

- Relationships take effort, and relational partners use 3 primary skills to maintain/sustain relationships.

- When relationship terminate, relational partners use a variety of strategies.

Exercises

- In terms of romantic attraction, which adage do you think is more true and why? “Birds of a feather flock together” or “Opposites attract.”

- List some examples of how you see passionate and companionate love play out in television shows or movies. Do you think this is an accurate portrayal of how love is experienced in romantic relationships? Why or why not?

- Social network overlap affects a romantic relationship in many ways. What are some positives and negatives of network overlap?

- Adler, R.B. & Proctor II, R. F. (2017). Looking out looking in (15th Ed.) Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. ↵

- Elaine Walster, Vera Aronson, Darcy Abrahams, and Leon Rottman, “Importance of Physical Attractiveness in Dating Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 4, no. 5 (1966): 508–16. ↵

- Chris Segrin and Jeanne Flora, Family Communication (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005), 112. ↵

- Jane E. Myers, Jayamala Madathil, and Lynne R. Tingle, “Marriage Satisfaction and Wellness in India and the United States: A Preliminary Comparison of Arranged Marriages and Marriages of Choice,” Journal of Counseling and Development 83 (2005): 183–87. ↵

- Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 32–51. ↵

- Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 32–51. ↵

- Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 38–39. ↵

- Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 39. ↵

- Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed September 13, 2011, http://www.oed.com. ↵

- Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 46–47. ↵

- Susan S. Hendrick and Clyde Hendrick, “Romantic Love,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 204–5. ↵

- Robert M. Milardo and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 33. ↵

- Robert M. Milardo and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 37. ↵

- Robert M. Milardo and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 39. ↵

- Mary Madden and Amanda Lenhart, “Online Dating,” Pew Internet and American Life Project, March 5, 2006. ↵

- Canary, D. J, Cody, M. J. & Manusov, V. (2008). Intepersonal communication: A goals-based approach (4th Ed). Ne Yourk bedfor/St. Martin's. ↵

How do social media affect our interpersonal relationships, if at all? This is a question that has been addressed by scholars, commentators, and people in general. To provide some perspective, similar questions and concerns have been raised along with each major change in communication technology. New media, however, have been the primary communication change of the past few generations, which likely accounts for the attention they receive. Some scholars in sociology have decried the negative effects of new technology on society and relationships in particular, saying that the quality of relationships is deteriorating and the strength of connections is weakening (Richardson & Hessey, 2009).

Facebook greatly influenced our use of the word friend, although people’s conceptions of the word may not have changed as much. When someone “friends you” on Facebook, it doesn’t automatically mean that you now have the closeness and intimacy that you have with some offline friends. And research shows that people don’t regularly accept friend requests from or send them to people they haven’t met, preferring instead to have met a person at least once (Richardson & Hessey, 2009). Some users, though, especially adolescents, engage in what is called “friend-collecting behavior,” which entails users friending people they don’t know personally or that they wouldn’t talk to in person in order to increase the size of their online network (Christofides, Muise, & Desmarais, 2012). As we will discuss later, this could be an impression management strategy, as the user may assume that a large number of Facebook friends will make him or her appear more popular to others.

Although many have critiqued the watering down of the term friend when applied to Social networking sites (SNSs), specifically Facebook, some scholars have explored how the creation of these networks affects our interpersonal relationships and may even restructure how we think about our relationships. Even though a person may have hundreds of Facebook friends that he or she doesn’t regularly interact with on- or offline, just knowing that the network exists in a somewhat tangible form (catalogued on Facebook) can be comforting. Even the people who are distant acquaintances but are “friends” on SNS can serve important functions. Rather than users seeing these connections as pointless, frivolous, or stressful, they are often comforting background presences. A dormant network is a network of people with whom users may not feel obligated to explicitly interact but may find comfort in knowing the connections exist. Such networks can be beneficial, because when needed, a person may be able to more easily tap into that dormant network than they would an offline extended network. It’s almost like being friends on SNS keeps the communication line open, because both people can view the other’s profile and keep up with their lives even without directly communicating. This can help sustain tenuous friendships or past friendships and prevent them from fading away, which as we learned is a common occurrence as we go through various life changes.

A key part of interpersonal communication is impression management, and some forms of new media allow us more tools for presenting ourselves than others. SNS in many ways are platforms for self-presentation. Even more than blogs, web pages, and smartphones, the environment on an SNS like Facebook or Twitter facilitates self-disclosure in a directed way and allows others who have access to our profile to see our other “friends.” This convergence of different groups of people (close friends, family, acquaintances, friends of friends, colleagues, and strangers) can present challenges for self-presentation. Research shows half of all US adults have a profile on Facebook or another SNS (Vitak & Ellison). The fact that Facebook is expanding to different generations of users has coined a new phrase—“the graying of Facebook.” This is due to a large increase in users over the age of fifty-five. In fact, it has been stated the fastest-growing Facebook user group is women fifty-five and older, which is up more than 175 percent since fall 2008 (Gates, 2009). So now we likely have people from personal, professional, and academic contexts in our Facebook network, and those people are now more likely than ever to be from multiple generations. The growing diversity of our social media networks creates new challenges as we try to engage in impression management.

People fifty-five and older are using new media in increasing numbers.

Marg O’Connell – Grandma kicks it with the iPad

We should be aware that people form impressions of us based not just on what we post on our profiles but also on our friends and the content that they post on our profiles. In short, as in our offline lives, we are judged online by the company we keep (Walther et al., 2008). The difference is, though, that via Facebook a person (unless blocked or limited by privacy settings) can see our entire online social network and friends, which doesn’t happen offline. The information on our profiles is also archived, meaning there is a record the likes of which doesn’t exist in offline interactions. Recent research found that a person’s perception of a profile owner’s attractiveness is influenced by the attractiveness of the friends shown on the profile. In short, a profile owner is judged more physically attractive when his or her friends are judged as physically attractive, and vice versa. The profile owner is also judged as more socially attractive (likable, friendly) when his or her friends are judged as physically attractive. The study also found that complementary and friendly statements made about profile owners on their wall or on profile comments increased perceptions of the profile owner’s social attractiveness and credibility. An interesting, but not surprising, gender double standard also emerged. When statements containing sexual remarks or references to the profile owner’s excessive drinking were posted on the profile, perceptions of attractiveness increased if the profile owner was male and decreased if female (Walther et al., 2008).

Self-disclosure is a fundamental building block of interpersonal relationships, and new media make self-disclosures easier for many people because of the lack of immediacy, meaning the fact that a message is sent through electronic means arouses less anxiety or inhibition than would a face-to-face exchange. SNSs provide opportunities for social support. Research has found that Facebook communication behaviors such as “friending” someone or responding to a request posted on someone’s wall lead people to feel a sense of attachment and perceive that others are reliable and helpful (Vitak & Ellison). Much of the research on Facebook, though, has focused on the less intimate alliances that we maintain through social media. Since most people maintain offline contact with their close friends and family, Facebook is more of a supplement to interpersonal communication. Since most people’s Facebook “friend” networks are composed primarily of people with whom they have less face-to-face contact in their daily lives, Facebook provides an alternative space for interaction that can more easily fit into a person’s busy schedule or interest area. For example, to stay connected, both people don’t have to look at each other’s profiles simultaneously. I often catch up on a friend by scrolling through a couple of weeks of timeline posts rather than checking in daily.

The space provided by SNSs can also help reduce some of the stress we feel in regards to relational maintenance or staying in touch by allowing for more convenient contact. The expectations for regular contact with our Facebook friends who are in our extended network are minimal. An occasional comment on a photo or status update or an even easier click on the “like” button can help maintain those relationships. However, when we post something asking for information, help, social support, or advice, those in the extended network may play a more important role and allow us to access resources and viewpoints beyond those in our closer circles. And research shows that many people ask for informational help through their status updates (Vitak & Ellison).

These extended networks serve important purposes, one of which is to provide access to new information and different perspectives than those we may get from close friends and family. For example, since we tend to have significant others that are more similar to than different from us, the people that we are closest to are likely to share many or most of our beliefs, attitudes, and values. Extended contacts, however, may expose us to different political views or new sources of information, which can help broaden our perspectives. The content in this section hopefully captures what I’m sure you have already experienced in your own engagement with new media—that new media have important implications for our interpersonal relationships. Given that, we will end this chapter with a “Getting Competent” feature box that discusses some tips on how to competently use social media.

“Getting Competent”

Using Social Media Competently

We all have a growing log of personal information stored on the Internet, and some of it is under our control and some of it isn’t. We also have increasingly diverse social networks that require us to be cognizant of the information we make available and how we present ourselves. While we can’t control all the information about ourselves online or the impressions people form, we can more competently engage with social media so that we are getting the most out of it in both personal and professional contexts.

A quick search on Google for “social media dos and don’ts” will yield around 100,000 results, which shows that there’s no shortage of advice about how to competently use social media. I’ll offer some of the most important dos and don’ts that I found that relate to communication (Doyle, 2012). Feel free to do your own research on specific areas of concern.

Be consistent. Given that most people have multiple social media accounts, it’s important to have some degree of consistency. At least at the top level of your profile (the part that isn’t limited by privacy settings), include information that you don’t mind anyone seeing.

Know what’s out there. Since the top level of many social media sites are visible in Google search results, you should monitor how these appear to others by regularly (about once a month) doing a Google search using various iterations of your name. Putting your name in quotation marks will help target your results. Make sure you’re logged out of all your accounts and then click on the various results to see what others can see.

Think before you post. Software that enable people to take “screen shots” or download videos and tools that archive web pages can be used without our knowledge to create records of what you post. While it is still a good idea to go through your online content and “clean up” materials that may form unfavorable impressions, it is even a better idea to not put that information out there in the first place. Posting something about how you hate school or your job or a specific person may be done in the heat of the moment and forgotten, but a potential employer might find that information and form a negative impression even if it’s months or years old.

Be familiar with privacy settings. If you are trying to expand your social network, it may be counterproductive to put your Facebook or Twitter account on “lockdown,” but it is beneficial to know what levels of control you have and to take advantage of them. For example, I have a “Limited Profile” list on Facebook to which I assign new contacts or people with whom I am not very close. You can also create groups of contacts on various social media sites so that only certain people see certain information.

Be a gatekeeper for your network. Do not accept friend requests or followers that you do not know. Not only could these requests be sent from “bots” that might skim your personal info or monitor your activity; they could be from people that might make you look bad. Remember, we learned earlier that people form impressions based on those with whom we are connected. You can always send a private message to someone asking how he or she knows you or do some research by Googling his or her name or username.

- Identify information that you might want to limit for each of the following audiences: friends, family, and employers.

- Google your name (remember to use multiple forms and to put them in quotation marks). Do the same with any usernames that are associated with your name (e.g., you can Google your Twitter handle or an e-mail address). What information came up? Were you surprised by anything?

- What strategies can you use to help manage the impressions you form on social media?

Impression Formation

In the 21st Century, so much of what we do involves interacting with people online. How we present ourselves to others through our online persona (impression formation) is very important. How we communicate via social media and how professional our online persona is can be determining factors in getting a job.

It’s important to understand that in today’s world, anything you put online can be found by someone else. According to the 2018 CareerBuilder.com social recruiting survey, a survey of more than 1,000 hiring managers, 70% admit to screening potential employees using social media, and 66% use search engines to look up potential employees. In fact, having an online persona can be very beneficial. Fortyseven percent of hiring managers admit to not calling a potential employee when the employee does not have an online presence. You may be wondering what employers are looking for when they check out potential employees online. The main things employers look for are information to support someone’s qualifications (58%), whether or not an individual has a professional online persona (50%), to see what others say about the potential candidate (34%), and information that could lead a hiring manager to decide not to hire someone (22%).22 According to CareerBuilder.com, here are the common reasons someone doesn’t get a job because of her/his/their online presence:

• Job candidate posted provocative or inappropriate photographs, videos or information: 40 percent

• Job candidate posted information about their alcohol of drug use: 36 percent

• Job candidate made discriminatory comments related to race, gender, religion, etc.: 31 percent

• Job candidate was linked to criminal behavior: 30 percent

• Job candidate lied about qualifications: 27 percent

• Job candidate had poor communication skills: 27 percent

• Job candidate bad-mouthed their previous company or fellow employee: 25 percent

• Job candidate’s screen name was unprofessional: 22 percent

• Job candidate shared confidential information from previous employers: 20 percent

• Job candidate lied about an absence: 16 percent

• Job candidate posted too frequently: 12 percent23

As you can see, having an online presence is important in the 21st Century. Some people make the mistake of having no social media presence, which can backfire. In today’s social media society, having no online presence can look very strange to hiring managers. You should consider your social media presence as an extension of your resume. At the very least, you should have a profile on LinkedIn, the social networking site most commonly used by corporate recruiters.

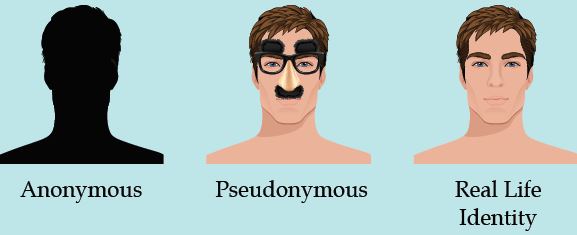

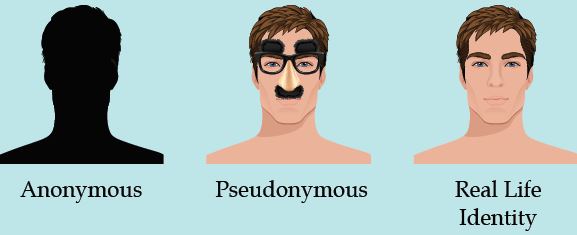

Types of Online Identities

Unlike traditional face to face interactions, online interactions can blur identities as people act in ways impossible in face to face interaction. Andrew F. Wood and Matthew J. Smith discussed three different ways that people express their identities online: anonymous, pseudonymous, and real life (Figure 12.9).49

Anonymous Identity

First, people in a CMC context can behave in a way that is completely anonymous. In this case, people in CMC interactions can communicate in a manner that conceals their actual identity. Now, it may be possible for some people to figure out who an anonymous person is (e.g., the NSA, the CIA), but if someone wants to maintain her or his anonymity, it’s usually possible to do so. Think about how many fake Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, and Grindr accounts exist. Some exist to try to persuade you to go to a website (often for illicit purposes like hacking your computer), while others may be “catfishing” for the fun of it.

Catfishing is a deceptive activity perpetrated by Internet predators when they fabricate online identities on social networking sites to lure unsuspecting victims into an emotional/romantic relationship. In the 2010 documentary Catfish, we are introduced to Yaniv “Nev” Schulman, a New York-based photographer, who starts an online relationship with an 8-year-old prodigy named Abby via Facebook. Over the course of nine months, the two exchange more than 1,500 messages, and Abby’s family (mother, father, and sister) also become friends with Nev on Facebook. Throughout the documentary, Nev and his brother Ariel (who is also the documentarian) start noticing inconsistencies in various stories that are being told. Music that was allegedly created by Abby is found to be taken from YouTube. Ariel convinces Nev to continue the relationship knowing that there are inconsistencies and lies just to see how it will all play out. The success of Catfish spawned a television show by the same name on MTV.

From this one story, we can easily see the problems that can arise from anonymity on the Internet. Often behavior that would be deemed completely inappropriate in a face to face encounter suddenly becomes appropriate because it’s deemed “less real” by some. One of the major problems with online anonymity has been cyberbullying. People today can post horrible things about one another online without any worry that the messages will be linked back to them directly. Unlike face to face bullying victims who leave the bullying behind when they leave school, teens facing cyberbullying cannot even find peace at home because the Internet follows them everywhere. In 2013 12-year-old Rebecca Ann Sedwick committed suicide after being the perpetual victim of cyberbullying through social media apps on her phone. Rebecca suffered a barrage of bullying for over a year and by around 15 different girls in her school. Sadly, Rebecca’s tale is one that is all too familiar in today’s world. Nine percent of middle-school students reported being victims of cyberbullying, and there is a relationship between victimization and suicidal ideation.

It’s also important to understand that cyberbullying isn’t just a phenomenon that happens with children. A 2009 survey of Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union members, found that 34% of respondents faced FtF bullying, and 10.7% faced cyberbullying. All of the individuals who were targets of cyberbullying were also bullied FtF.51

Many people prefer anonymity when interacting with others online, and there can be legitimate reasons to engage in online interactions with others. For example, when one of our authors was coming out as LGBTQIA+, our coauthor regularly talked with people online as they melded the new LGBTQIA+ identity with their Southern and Christian identities. Having the ability to talk anonymously with others allowed our coauthor to gradually come out by forming anonymous relationships with others dealing with the same issues.

Pseudonymous Identity

The second category of interaction is pseudonymous. Wood and Smith used the term pseudonymous because of the prefix “pseudonym”: “Pseudonym comes from the Latin words for ‘false’ and ‘name,’ and it provides an audience with the ability to attribute statements and actions to a common source [emphasis in original].”52 Whereas an anonym allows someone to be completely anonymous, a pseudonym “allows one to contribute to the fashioning of one’s own image.”53 Using pseudonyms is hardly something new. Famed mystery author Agatha Christi wrote over 66 detective novels, but still published six romance novels using the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. Bestselling science fiction author Michael Crichton (of Jurassic Park fame), wrote under three different pseudonyms (John Lange, Jeffery Hudson, and Michael Douglas) when he was in medical school.

Even J. K. Rowling (of Harry Potter fame) used the pseudonym Robert Galbraith to write her follow-up novel to the series, The Cuckoo’s Calling (2013). Rowling didn’t want the media hype or inflated reader expectations while writing her follow-up novel. Unfortunately for Rowling, the secret didn’t stay hidden very long.

The veneer of the Internet allows us to determine how much of an identity we wish to front in online presentations. These images can range from a vague silhouette to a detailed snapshot. Whatever the degree of identity presented, however, it appears that control and empowerment are benefits for users of these communication technologies.”54

Some people even adopt a pseudonym because their online actions may not be “on-brand” for their day-job or because they don’t want to be fully exposed online.

Real Life Identity

Lastly, some people have their real-life identities displayed online. You can find people on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc…. Some realize that this behavior is a part of their professional persona, so they don’t put anything on one of these sites they wouldn’t want other professionals to see and read. When it comes to people in the public eye, most of them use some variation of their real names to enhance their brands. That’s not to say that many of these same people don’t have multiple online accounts, some of which may be completely anonymous or even pseudonymous.

Interpersonal Communication in Mediated Contexts[1]

In today’s world, we all spend a lot of time on various devices designed to make our lives easier. From smartphones to social media, we are all in constant contact with family, friends, coworkers, etc. Since the earliest days of communication technologies, we have always used these technologies to interact with one another. This chapter will examine how technology mediates our interpersonal relationships.

Allowing People to Communicate

The early Internet was not exactly designed for your average user, so it took quite a bit of skill and “know how” to use the Internet and find information. Of course, while the Internet was developing, so was its capability for allowing people to communicate and interact with one another. In 1971, Ray Tomlinson sent a message from one computer to another computer sitting right next to it, sending the message through ARPANET and creating the first electronic email. In addition to email, another breakthrough in computer-mediated communication was the development of Internet forums or message/bulletin boards, which are online discussion sites where people can hold conversations in the form of posted messages. As you can see, from the earliest days of the Internet, people were using the Internet as a tool to communicate and interact with people who had similar interests. Today, there are hundreds of ways to connect with others in an online environment.

Synchronous and Asynchronous Communication

Synchronous communication happens in real time, like having a class discussion in a face-to-face setting or talking to a someone after class. But you can communicate synchronously in an online environment too, through the use of tools like online chat; Internet voice of video calling systems like Skype or Google Hang-outs; or through the use of web-based video conferencing software like WebEx, Zoom, or Collaborate. Another popular form of synchronous online communication is gaming. For example, in Figure 12.5, Sam and Pat are in some kind of underworld, fiery landscape. Pat is playing a witch character, and Sam is playing a vampire character. The two can coordinate their movements to accomplish in-game tasks because they can talk freely to one another while playing the game in real time.

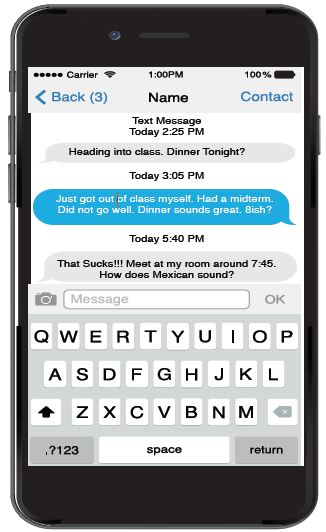

Conversely, asynchronous communication is the exchange of messages with a time lag. In other words, in asynchronous communication, people can communicate on their own schedules as time permits instead of in real time. For example, Figure 12.6 shows a conversation between two college students. In this case, two college students are using SMS, commonly called texting) to interact with each other. The conversation starts at 2:25 PM. The first person initiates the conversation but doesn’t get a response until 3:05 PM. The third turn in the interaction then doesn’t happen until 5:40 PM. In this exchange, the two people interacting can send responses at their convenience, which is one of the main reasons people often rely on asynchronous communication. Other common forms of asynchronous communication include emails, instant messaging, and online discussions.

New Media

The early 1980s saw the development of what we call the new media: new technologies and old technologies in new combinations. They are muddying if not eliminating the differences between media. On the iPad, newspapers, television, and radio stations look similar: they all have text, pictures, video, and links.

Increasingly, Americans, particularly students, are obtaining information on tablets and from websites, blogs, discussion boards, video-sharing sites, such as YouTube, and social networking sites, like Facebook, podcasts, and Twitter. And of course, there is the marvel of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia to which so many people (four hundred million every month) go to for useful, if not always reliable, information.

Netiquette

Over the years, numerous norms have developed to help individuals communicate in the CMC context. They’re so common that we have a term for them, netiquette. Netiquette is the set of professional and social rules and norms that are considered acceptable and polite when interacting with another person(s) through mediating technologies. Let’s break down this definition.

Contexts

First, our definition of netiquette emphasizes that different contexts can create different netiquette needs. Specifically, how one communicates professionally and how one communicates socially are often quite different. For example, you may find it entirely appropriate to say, “What’s up?!” at the beginning of an email to a friend, but you would not find it appropriate to start an email to your boss in this same fashion. Furthermore, it may be entirely appropriate to downplay or disregard spelling errors or grammatical problems in a text you send to a friend, but it is completely inappropriate to have those same errors and problems in a text sent to a professional-client or coworker. One of the biggest challenges many employers have with young employees who are fresh out of college is that they don’t know how to differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate communicative behavior in differing contexts. This lack of professionalism is also a problem commonly discussed by college and university faculty and staff. Think about the last email you sent to one of your professors? Was this email professional? Did you remember to sign your name? You’d be amazed at the lack of professionalism many college and university faculty and staff see in the emails sent by your peers.

Rules and Norms

Second, our definition of netiquette combines both rules and norms. Part of being a competent communicator in a CMC environment is knowing what the rules are and respecting them. For example, if you know that Twitter’s rules ban hate speech, then engaging in hate speech using the Twitter platform shows a disregard for the rules and would not be considered appropriate behavior. In essence, hate speech is anti-netiquette. We also do not want to ignore the fact that in different CMC contexts, different norms often develop. For example, maybe you’re taking an online course and you’re required to engage in weekly discussions. One common norm in an online class is to check the previous replies to a post before posting your reply. If you don’t, then you are jumping into a conversation that’s already occurred and throwing your two-cents in without knowing what’s happening.

Acceptable and Polite CMC Behavior

Third, netiquette attempts to govern what is both acceptable and polite. Yelling via a text message may be acceptable to some of your friends, but is it polite given that typing in all caps is generally seen as yelling? Being polite shows others respect and demonstrates socially appropriate behaviors. If you’ve spent any time online recently, you may have noticed that it can definitely feel toxic. There are many trolls, making the Internet a place where civil interactions are hard to come by. Mitch Abblett came up with five specific guidelines for interacting with others online:

1. Be kind and compassionately courteous with all posts and comments.

2. No hate speech, bullying, derogatory or biased comments regarding self, others in the community, or others in general.

3. No Promotions or Spam.

4. Do not give mental health advice.

5. Respect everyone’s privacy and be thoughtful in the nature and depth of your sharing.14

Think about your interactions with others in the online world. Have you ever communicated with others without considering whether your own intentions and attitude are appropriate?

Online Interaction

Fourth, our definition involves interacting with others. This interaction can be one-on-one, or this interaction can be one-to-many. The first category, one-on-one, is more in the wheelhouse of interpersonal communication. Examples include sending a text to one person, sending an email to one person, talking to one person via Skype or Zoom, etc. The second category, one-to-many, requires its own set of rules and norms. Some examples of common one-to-many CMC could include engaging in a group chat via texting, “replying all” to an email received, being interviewed by a committee via Skype, etc. Notice that our examples for one-to-many involve the same technologies used for one-on-one communication. However, the norms may be different for each.

Range of Mediating Technologies

Lastly, netiquette can vary based on the different types of mediating technologies. For example, it may be considered entirely appropriate for you to scream, yell, and curse when your playing with your best friend on Fortnite, but it wouldn’t be appropriate to use the same communicative behaviors when engaging in a video conference over Skype. Both technologies use VoIP, but the platforms and the contexts are very different, so they call for different types of communicative behaviors. Some differences will exist in netiquette based on whether you’re in an entirely text-based medium (e.g., email, texting) or one where people can see you (e.g., Skype, WebEx, Zoom). Ultimately, engaging in netiquette requires you to learn what is considered acceptable and polite behavior across a range of different technologies.

Impression Formation

In the 21st Century, so much of what we do involves interacting with people online. How we present ourselves to others through our online persona (impression formation) is very important. How we communicate via social media and how professional our online persona is can be determining factors in getting a job.

It’s important to understand that in today’s world, anything you put online can be found by someone else. According to the 2018 CareerBuilder.com social recruiting survey, a survey of more than 1,000 hiring managers, 70% admit to screening potential employees using social media, and 66% use search engines to look up potential employees. In fact, having an online persona can be very beneficial. Fortyseven percent of hiring managers admit to not calling a potential employee when the employee does not have an online presence. You may be wondering what employers are looking for when they check out potential employees online. The main things employers look for are information to support someone’s qualifications (58%), whether or not an individual has a professional online persona (50%), to see what others say about the potential candidate (34%), and information that could lead a hiring manager to decide not to hire someone (22%).22 According to CareerBuilder.com, here are the common reasons someone doesn’t get a job because of her/his/their online presence:

• Job candidate posted provocative or inappropriate photographs, videos or information: 40 percent

• Job candidate posted information about their alcohol of drug use: 36 percent

• Job candidate made discriminatory comments related to race, gender, religion, etc.: 31 percent

• Job candidate was linked to criminal behavior: 30 percent

• Job candidate lied about qualifications: 27 percent

• Job candidate had poor communication skills: 27 percent

• Job candidate bad-mouthed their previous company or fellow employee: 25 percent

• Job candidate’s screen name was unprofessional: 22 percent

• Job candidate shared confidential information from previous employers: 20 percent

• Job candidate lied about an absence: 16 percent

• Job candidate posted too frequently: 12 percent23

As you can see, having an online presence is important in the 21st Century. Some people make the mistake of having no social media presence, which can backfire. In today’s social media society, having no online presence can look very strange to hiring managers. You should consider your social media presence as an extension of your resume. At the very least, you should have a profile on LinkedIn, the social networking site most commonly used by corporate recruiters.

Types of Online Identities

Unlike traditional face to face interactions, online interactions can blur identities as people act in ways impossible in face to face interaction. Andrew F. Wood and Matthew J. Smith discussed three different ways that people express their identities online: anonymous, pseudonymous, and real life (Figure 12.9).49

Anonymous Identity

First, people in a CMC context can behave in a way that is completely anonymous. In this case, people in CMC interactions can communicate in a manner that conceals their actual identity. Now, it may be possible for some people to figure out who an anonymous person is (e.g., the NSA, the CIA), but if someone wants to maintain her or his anonymity, it’s usually possible to do so. Think about how many fake Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, and Grindr accounts exist. Some exist to try to persuade you to go to a website (often for illicit purposes like hacking your computer), while others may be “catfishing” for the fun of it.

Catfishing is a deceptive activity perpetrated by Internet predators when they fabricate online identities on social networking sites to lure unsuspecting victims into an emotional/romantic relationship. In the 2010 documentary Catfish, we are introduced to Yaniv “Nev” Schulman, a New York-based photographer, who starts an online relationship with an 8-year-old prodigy named Abby via Facebook. Over the course of nine months, the two exchange more than 1,500 messages, and Abby’s family (mother, father, and sister) also become friends with Nev on Facebook. Throughout the documentary, Nev and his brother Ariel (who is also the documentarian) start noticing inconsistencies in various stories that are being told. Music that was allegedly created by Abby is found to be taken from YouTube. Ariel convinces Nev to continue the relationship knowing that there are inconsistencies and lies just to see how it will all play out. The success of Catfish spawned a television show by the same name on MTV.

From this one story, we can easily see the problems that can arise from anonymity on the Internet. Often behavior that would be deemed completely inappropriate in a face to face encounter suddenly becomes appropriate because it’s deemed “less real” by some. One of the major problems with online anonymity has been cyberbullying. People today can post horrible things about one another online without any worry that the messages will be linked back to them directly. Unlike face to face bullying victims who leave the bullying behind when they leave school, teens facing cyberbullying cannot even find peace at home because the Internet follows them everywhere. In 2013 12-year-old Rebecca Ann Sedwick committed suicide after being the perpetual victim of cyberbullying through social media apps on her phone. Rebecca suffered a barrage of bullying for over a year and by around 15 different girls in her school. Sadly, Rebecca’s tale is one that is all too familiar in today’s world. Nine percent of middle-school students reported being victims of cyberbullying, and there is a relationship between victimization and suicidal ideation.

It’s also important to understand that cyberbullying isn’t just a phenomenon that happens with children. A 2009 survey of Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union members, found that 34% of respondents faced FtF bullying, and 10.7% faced cyberbullying. All of the individuals who were targets of cyberbullying were also bullied FtF.51

Many people prefer anonymity when interacting with others online, and there can be legitimate reasons to engage in online interactions with others. For example, when one of our authors was coming out as LGBTQIA+, our coauthor regularly talked with people online as they melded the new LGBTQIA+ identity with their Southern and Christian identities. Having the ability to talk anonymously with others allowed our coauthor to gradually come out by forming anonymous relationships with others dealing with the same issues.

Pseudonymous Identity

The second category of interaction is pseudonymous. Wood and Smith used the term pseudonymous because of the prefix “pseudonym”: “Pseudonym comes from the Latin words for ‘false’ and ‘name,’ and it provides an audience with the ability to attribute statements and actions to a common source [emphasis in original].”52 Whereas an anonym allows someone to be completely anonymous, a pseudonym “allows one to contribute to the fashioning of one’s own image.”53 Using pseudonyms is hardly something new. Famed mystery author Agatha Christi wrote over 66 detective novels, but still published six romance novels using the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. Bestselling science fiction author Michael Crichton (of Jurassic Park fame), wrote under three different pseudonyms (John Lange, Jeffery Hudson, and Michael Douglas) when he was in medical school.

Even J. K. Rowling (of Harry Potter fame) used the pseudonym Robert Galbraith to write her follow-up novel to the series, The Cuckoo’s Calling (2013). Rowling didn’t want the media hype or inflated reader expectations while writing her follow-up novel. Unfortunately for Rowling, the secret didn’t stay hidden very long.

The veneer of the Internet allows us to determine how much of an identity we wish to front in online presentations. These images can range from a vague silhouette to a detailed snapshot. Whatever the degree of identity presented, however, it appears that control and empowerment are benefits for users of these communication technologies.”54

Some people even adopt a pseudonym because their online actions may not be “on-brand” for their day-job or because they don’t want to be fully exposed online.

Real Life Identity

Lastly, some people have their real-life identities displayed online. You can find people on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc…. Some realize that this behavior is a part of their professional persona, so they don’t put anything on one of these sites they wouldn’t want other professionals to see and read. When it comes to people in the public eye, most of them use some variation of their real names to enhance their brands. That’s not to say that many of these same people don’t have multiple online accounts, some of which may be completely anonymous or even pseudonymous.

Nonverbal Cues

One issue related to CMC is nonverbal communication. Historically, most of the media people have used to interact with one another have been asynchronous and text-based, making it difficult to fully ascertain the meaning behind a string of words. Mary J. Culnan and M. Lynne Markus believe that the functions nonverbal behaviors meet in interpersonal interactions simply go unmet in CMC (1987). If so, interpersonal communication must always be inherently impersonal when it’s conducted using computer-mediated technologies. This perspective has three underlying assumptions:

- Communication mediated by technology filters out communicative cues found in face to face interaction,

- Different media filter out or transmit different cues, and

- Substituting technology-mediated for face to face communication will result in predictable changes in intrapersonal and interpersonal variables.

First, CMC interactions “filter out” communicative cues found in face to face interactions. For example, if you’re on the telephone with someone, you can’t make eye contact or see their gestures, facial expressions, etc.… If you’re reading an email, you have no nonverbal information to help you interpret the message because there is none. In these examples, the nonverbal cues have been “filtered out” by the media being used.

Unfortunately, even if we don’t have the nonverbals to help us interpret a message, we interpret the message using our perception of how the sender intended us to understand this message, which is often wrong. How many times have you seen an incorrectly read text or email start a conflict? Of course, one of the first attempts to recover some sense of nonverbal meaning was the emoticon that we discussed earlier in this chapter.

One early realization about email and message boards was that people relied solely on text to interpret messages, which lacked nonverbal cues to aid in interpretation. On September 19, 1982, Scott Fahlman, a research professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon, came up with an idea. You see, at Carnegie Mellon in the early 1980s (like most research universities at the time), they had their own bulletin board system (BBS), which discussed everything from campus politics to science fiction. As Fahlman noted,

“Given the nature of the community, a good many of the posts were humorous, or at least attempted humor.” But “The problem was that if someone made a sarcastic remark, a few readers would fail to get the joke and each of them would post a lengthy diatribe in response.”4

After giving some thought to the problem, he posted the message seen in Figure 12.3. Thus, the emoticon (emotion icon) was born. An emoticon is a series of characters that are designed to help readers interpret a writer’s intended tone or the feelings the writer intended to convey. Over the years, many different emoticons were created like the smiley and sad faces, lol (laughing out loud), ROFL (rolling on the floor laughing), :-O (surprise), :-* (kiss),

How do social media affect our interpersonal relationships, if at all? This is a question that has been addressed by scholars, commentators, and people in general. To provide some perspective, similar questions and concerns have been raised along with each major change in communication technology. New media, however, have been the primary communication change of the past few generations, which likely accounts for the attention they receive. Some scholars in sociology have decried the negative effects of new technology on society and relationships in particular, saying that the quality of relationships is deteriorating and the strength of connections is weakening (Richardson & Hessey, 2009).

Facebook greatly influenced our use of the word friend, although people’s conceptions of the word may not have changed as much. When someone “friends you” on Facebook, it doesn’t automatically mean that you now have the closeness and intimacy that you have with some offline friends. And research shows that people don’t regularly accept friend requests from or send them to people they haven’t met, preferring instead to have met a person at least once (Richardson & Hessey, 2009). Some users, though, especially adolescents, engage in what is called “friend-collecting behavior,” which entails users friending people they don’t know personally or that they wouldn’t talk to in person in order to increase the size of their online network (Christofides, Muise, & Desmarais, 2012). As we will discuss later, this could be an impression management strategy, as the user may assume that a large number of Facebook friends will make him or her appear more popular to others.