Main Body

Module 8 Expressionism & Cubism

(Matisse, Kirchner, Kandinsky, Picasso)

Introduction: Fauvism

Henri Matisse “The Red Studio”

[Smarthistory > Expressionism to Pop Art > Early Abstraction: Fauvism, Expressionism, and Cubism > Fauvism & Matisse > Matisse, The Red Studio]

Oil on canvas, 1911 (MoMA)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner “Street Berlin”

Walk the streets of 1913 Berlin with the Expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Vasily Kandinsky “Improvisation 28”

Improvisation 28 (second version), 1912, oil on canvas, 111.4 x 162.1 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Cubism

Pablo Picasso “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”

Essay by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, CC-BY-NC

Cézanne’s ghost, Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre, and Picasso’s ego

One of the most important canvases of the twentieth century, Picasso’s great breakthrough painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was constructed in response to several significant sources. First amongst these was his confrontation with Cézanne’s great achievement at the posthumous retrospective mounted in Paris a year after the artist’s death in 1907.

The retrospective exhibition forced the young Picasso, Matisse, and many other artists to contend with the implications of Cézanne’s art. Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre of 1906 was one of the first of many attempts to do so, and the newly completed work was quickly purchased by Leo & Gertrude Stein and hung in their living room so that all of their circle of avant-garde writers and artists could see and praise it. And praise it they did. Here was the promise of Cézanne fulfilled—and one which incorporated lessons learned from Seurat and Van Gogh, no less! This was just too much for the young Spaniard.

Pablo becomes Picasso

By all accounts, Picasso’s intensely competitive nature literally forced him to out do his great rival. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is the result of this effort. Let’s compare canvases. Matisse’s landscape is a broad open field with a deep recessionary vista. The figures are uncrowded. They describe flowing arabesques that in turn relate to the forms of nature that surround them. Here is languid sensuality set in the mythic past of Greece’s golden age.

In very sharp contrast, Picasso, intent of making a name for himself (rather like the young Manet and David), has radically compressed the space of his canvas and replaced sensual eroticism with a kind of aggressively crude pornography. (Note, for example, the squatting figure at the lower right.) His space is interior, closed, and almost claustrophobic. Like Matisse’s later Blue Nude (itself a response to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon), the women fill the entire space and seem trapped within it. No longer set in a classical past, Picasso’s image is clearly of our time. Here are five prostitutes from an actual brothel, located on a street named Avignon in the red-light district in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia in northern Spain—a street, by the way, which Picasso had frequented.

Picasso has also dispensed with Matisse’s clear, bright pigments. Instead, the artist chooses deeper tones befitting urban interior light. Gone too, is the sensuality that Matisse created. Picasso has replaced the graceful curves of Bonheur de Vivre with sharp, jagged, almost shattered forms. The bodies of Picasso’s women look dangerous as if they were formed of shards of broken glass. Matisse’s pleasure becomes Picasso’s apprehension. But while Picasso clearly aims to “out do” Matisse, to take over as the most radical artist in Paris, he also acknowledges his debts. Compare the woman standing in the center of Picasso’s composition to the woman who stands with elbows raised at the extreme left of Matisse’s canvas: like a scholar citing a borrowed quotation, Picasso footnotes.

The creative vacuum-cleaner

Picasso draws on many other sources to construct Les Demoiselles D’Avignon. In fact, a number of artists stopped inviting him to their studio because he would so freely and successfully incorporate their ideas into his own work, often more successfully than the original artist. Indeed, Picasso has been likened to a “creative vacuum cleaner,” sucking up every new idea that he came across. While that analogy might be a little coarse, it is fair to say that he had an enormous creative appetite. One of several historical sources that Picasso pillaged is archaic art, demonstrated very clearly by the left-most figure of the painting, who stands stiffly on legs that look awkwardly locked at the knee. Her right arm juts down while her left arm seems dislocated (this arm is actually a vestige of a male figure that Picasso eventually removed). Her head is shown in perfect profile with large almond shaped eyes and a flat abstracted face. She almost looks Egyptian. In fact, Picasso has recently seen an exhibition of archaic (an ancient pre-classical style) Iberian (from Iberia–the land mass that makes up Spain and Portugal) sculpture at the Louvre. Instead of going back to the sensual myths of ancient Greece, Picasso is drawing on the real thing and doing so directly. By the way, Picasso purchased, from Apollinaire’s secretary, two archaic Iberian heads that she had stolen from the Louvre! Some have suggested that they were taken at Picasso’s request. Years later Picasso would anonymously return them.

Sponteneity, carefully choreographed

Because the canvas is roughly handled, it is often thought to be a spontaneous creation, conceived directly. This is not the case. It was preceded by nearly one hundred sketches. These studies depict different configurations. In some there are two men in addition to the women. One is a sailor. He sits in uniform in the center of the composition before a small table laden with fruit, a traditional symbol of sexuality. Another man originally entered from the left. He wore a brown suit and carried a textbook, he was meant to be a medical student.

The (male) Artist’s Gaze

Each of these male figures was meant to symbolize an aspect of Picasso. Or, more exactly, how Picasso viewed these women. The sailor is easy to figure out. The fictive sailor has been at sea for months, he is an obvious reference to pure sexual desire. The medical student is trickier. He is not there to look after the women’s health but he does see them with different eyes. While the sailor represents pure lust, the student sees the women from a more analytic perspective. He understands how their bodies are constructed, etc. Could it be that Picasso was expressing the ways that he saw these women? As objects of desire, yes, but also, with a knowledge of anatomy probably superior to many doctors. What is important is that Picasso decides to remove the men. Why? Well, to begin, we might imagine where the women focused their attention in the original composition. If men are present, the prostitutes attend to them. By removing these men, the image is no longer self-contained. The women now peer outward, beyond the confines of the picture plane that ordinarily protect the viewer’s anonymity. If the women peer at us, like in Manet’s Olympia of 1863, we, as viewers, have become the customers. But this is the twentieth century, not the nineteenth and Picasso is attempting a vulgar directness that would make even Manet cringe.

Picasso’s perception of space

So far, we have examined the middle figure which relates to Matisse’s canvas; the two masked figures on the right side who refer, by their aggression, to Picasso’s fear of disease; and, we have linked the left-most figure to archaic Iberian sculpture and Picasso’s attempt to elicit a sort of crude primitive directness. That leaves only one woman unaccounted for. This is the woman with her right elbow raised and her left hand on a sheet pulled across her left thigh. The table with fruit that had originally been placed at the groin of the sailor is no longer round, it has lengthened, sharpened, and has been lowered to the edge of the canvas. This table/phallus points to this last woman. Picasso’s meaning is clear, the still life of fruit on a table, this ancient symbol of sexuality, is the viewer’s erect penis and it points to the woman of our choice. Picasso was no feminist. In his vision, the viewer is male.

Although explicit, this imagery only points to the key issue. The woman that has been chosen is handled distinctly in terms of her relation to the surrounding space. Yes, more about space. Throughout the canvas, the women and the drapery (made of both curtains and sheets) are fractured and splintered. Here is Picasso’s response to Cezanne and Matisse. The women are neither before nor behind. As in Matisse’s Red Studio, which will be painted four years later, Picasso has begun to try to dissolve the figure/ground relationship. Now look at the woman that Picasso tells us we have chosen. Her legs are crossed and her hand rests behind her head, but although she seems to stand among the others, her position is really that of a figure that lies on her back. The problem is, we see her body perpendicular to our line of sight. Like Matisse and Cezanne before him, Picasso here renders two moments in time: as you may have figured out, we first look across at the row of women, and then we look down on to the prostitute of our/Picasso’s choice.

African masks, Women colonized

The two figures at the right are the most aggressively abstracted with faces rendered as if they wear African masks. By 1907, when this painting was produced, Picasso had begun to collect such work. Even the striations that represent scarification is evident. Matisse and Derain had a longer standing interest in such art, but Picasso said that it was only after wandering into the Palais du Trocadero, Paris’s ethnographic museum, that he understood the value of such art. Remember, France was a major colonial power in Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Much African art was ripped from its original geographic and artistic context and sold in Paris. Although Picasso would eventually become more sophisticated regarding the original uses and meaning of the non-Western art that he collected, in 1907 his interest was largely based on what he perceived as its alien and aggressive qualities.

William Rubin, once the senior curator of the department of painting and sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, and a leading Picasso scholar, has written extensively about this painting. He has suggested that while the painting is clearly about desire (Picasso’s own), it is also an expression of his fear. We have already established that Picasso frequented brothels at this time so his desire isn’t in question, but Rubin makes the case that this is only half the story. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is also about Picasso’s intense fear…his dread of these women or more to the point, the disease that he feared they would transmit to him. In the era before antibiotics, contracting syphilis was a well founded fear. Of course, the plight of the women seems not to enter Picasso’s story.

Pablo Picasso “Guernica”

Text by Lynn Robinson, CC-BY-NC

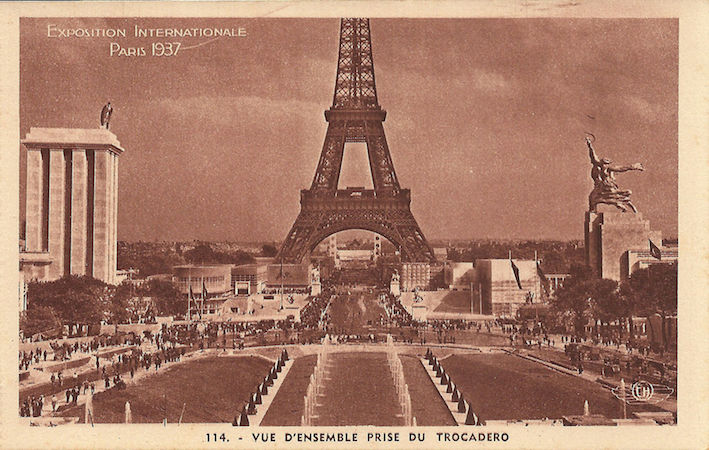

What would be the best way today to protest against a war? How could you influence the largest number of people? In 1937, Picasso expressed his outrage against war with Guernica, his enormous mural-sized painting displayed to millions of visitors at the Paris World’s Fair. It has since become the twentieth century’s most powerful indictment against war, a painting that still feels intensely relevant today.

Antiwar icon

Much of the painting’s emotional power comes from its overwhelming size, approximately eleven feet tall and twenty five feet wide. Guernica is not a painting you observe with spatial detachment; it feels like it wraps around you, immerses you in its larger-than-life figures and action. And although the size and multiple figures reference the long tradition of European history paintings, this painting is different because it challenges rather than accepts the notion of war as heroic. So why did Picasso paint it?

Commission

In 1936, Picasso (who was Spanish) was asked by the newly elected Spanish Republican government to paint an artwork for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. The official theme of the Exposition was a celebration of modern technology. Yet Picasso painted an overtly political painting, a subject in which he had shown little interest up to that time. What had happened to inspire it?

Crimes against humanity: an act of war

In 1936, a civil war began in Spain between the democratic Republican government and fascist forces, led by General Francisco Franco, attempting to overthrow them. Picasso’s painting is based on the events of April 27, 1937, when Hitler’s powerful German air force, acting in support of Franco, bombed the village of Guernica in northern Spain, a city of no strategic military value. It was history’s first aerial saturation bombing of a civilian population. It was a cold-blooded training mission designed to test a new bombing tactic to intimidate and terrorize the resistance. For over three hours, twenty five bombers dropped 100,000 pounds of explosive and incendiary bombs on the village, reducing it to rubble. Twenty more fighter planes strafed and killed defenseless civilians trying to flee. The devastation was appalling: fires burned for three days, and seventy percent of the city was destroyed. A third of the population, 1600 civilians, were wounded or killed.

Picasso hears the news

On May 1, 1937, news of the atrocity reached Paris. Eyewitness reports filled the front pages of local and international newspapers. Picasso, sympathetic to the Republican government of his homeland, was horrified by the reports of devastation and death. Guernica is his visual response, his memorial to the brutal massacre. After hundreds of sketches, the painting was done in less than a month and then delivered to the Fair’s Spanish Pavilion, where it became the central attraction. Accompanying it were documentary films, newsreels and graphic photographs of fascist brutalities in the civil war. Rather than the typical celebration of technology people expected to see at a world’s fair, the entire Spanish Pavilion shocked the world into confronting the suffering of the Spanish people.

Later, in the 1940s, when Paris was occupied by the Germans, a Nazi officer visited Picasso’s studio. “Did you do that?” he is said to have asked Picasso while standing in front of a photograph of the painting. “No,” Picasso replied, “you did.”

World traveler

When the fair ended, the Spanish Republican forces sent Guernica on an international tour to create awareness of the war and raise funds for Spanish refugees. It traveled the world for 19 years and then was loaned for safekeeping to The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Picasso refused to allow it to return to Spain until the country “enjoyed public liberties and democratic institutions,” which finally occurred in 1981. Today the painting permanently resides in the Reina Sofia, Spain’s national museum of modern art in Madrid.

What can we see?

This painting is not easy to decipher. Everywhere there seems to be death and dying. As our eyes adjust to the frenetic action, figures begin to emerge. On the far left is a woman, head back, screaming in pain and grief, holding the lifeless body of her dead child. This is one of the most devastating and unforgettable images in the painting. To her right is the head and partial body of a large white bull, the only unharmed and calm figure amidst the chaos. Beneath her, a dead or wounded man with a severed arm and mutilated hand clutches a broken sword. Only his head and arms are visible; the rest of his body is obscured by the overlapping and scattered parts of other figures. In the center stands a terrified horse, mouth open screaming in pain, its side pierced by a spear. On the right are three more women. One rushes in, looking up at the stark light bulb at the top of the scene. Another leans out of the window of a burning house, her long extended arm holding a lamp, while the third woman appears trapped in the burning building, screaming in fear and horror. All their faces are distorted in agony. Eyes are dislocated, mouths are open, tongues are shaped like daggers.

Color

Picasso chose to paint Guernica in a stark monochromatic palette of gray, black and white. This may reflect his initial encounter with the original newspaper reports and photographs in black and white; or perhaps it suggested to Picasso the objective factuality of an eye witness report. A documentary quality is further emphasized by the textured pattern in the center of the painting that creates the illusion of newsprint. The sharp alternation of black and white contrasts across the painting surface also creates dramatic intensity, a visual kinetic energy of jagged movement.

Visual complexity

On first glance, Guernica’s composition appears confusing and chaotic; the viewer is thrown into the midst of intensely violent action. Everything seems to be in flux. The space is compressed and ambiguous with the shifting perspectives and multiple viewpoints characteristic of Picasso’s earlier Cubist style. Images overlap and intersect, obscuring forms and making it hard to distinguish their boundaries. Bodies are distorted and semi-abstracted, the forms discontinuous and fragmentary. Everything seems jumbled together, while sharp angular lines seem to pierce and splinter the dismembered bodies. However, there is in fact an overriding visual order. Picasso balances the composition by organizing the figures into three vertical groupings moving left to right, while the center figures are stabilized within a large triangle of light.

Symbolism

There has been almost endless debate about the meaning of the images in Guernica. Questioned about its possible symbolism, Picasso said it was simply an appeal to people about massacred people and animals. ”In the panel on which I am working, which I call Guernica, I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain into an ocean of pain and death.” The horse and bull are images Picasso used his entire career, part of the life and death ritual of the Spanish bullfights he first saw as a child. Some scholars interpret the horse and bull as representing the deadly battle between the Republican fighters (horse) and Franco’s fascist army (bull). Picasso said only that the bull represented brutality and darkness, adding “It isn’t up to the painter to define the symbols. Otherwise it would be better if he wrote them out in so many words. The public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them.”

In the end, the painting does not appear to have one exclusive meaning. Perhaps it is that very ambiguity, the lack of historical specificity, or the fact that brutal wars continue to be fought, that keeps Guernica as timeless and universally relatable today as it was in 1937.