Chapter 1: Introduction to the field of Communication Studies

1.4 Communication Competence

Learning Objectives

- Define communication competence.

- Explain each part of the definition of communication competence.

- Discuss strategies for developing communication competence.

- Identify characteristics of mindful communicators

Defining and Identifying Competence

Communication competence has become a focus in higher education over the past couple of decades as educational policymakers and advocates have stressed a “back to basics” mentality (McCroskey, 1984). The ability to communicate effectively is often included as a primary undergraduate learning goal along with other key skills like writing, critical thinking, and problem-solving. We have already defined communication and you probably know that to be competent at something means you know what you’re doing. When we combine these terms, we get the following definition, which has remained reasonably consistent over time: competent communication refers to the knowledge of effective and appropriate communication and the ability to use and adapt that knowledge in various contexts (Cooley & Roach, 1984; Adler et al., 2021).

|

Knowledge: The cognitive elements of competence include knowing how to do something and understanding why things are done the way they are (Hargie, 2011). |

|

Ability to use: Skilled at performing the communication behaviors. |

|

Adapting to various contexts: Ability use and adapt communication knowledge and skills across a variety of contexts. |

The first part of the definition we will unpack deals with knowledge. The cognitive elements of competence include knowing how to do something and understanding why things are done the way they are (Hargie, 2011). People can develop cognitive competence by observing and evaluating the actions of others. Cognitive competence can also be developed through instruction. Since you are currently taking a communication class, try to observe the communication concepts you are learning in the communication practices of others and yourself. This will help bring the concepts to life and also help you evaluate how communication in the real world matches up with communication concepts. As you build a repertoire of communication knowledge based on your experiential and classroom knowledge, you will also be moving towards developing behavioral competence.

The second part of the definition of communication competence that we will unpack is the ability to use. Individual factors affect our ability to do anything. Not everyone has the same athletic, musical, or intellectual ability. At the individual level, a person’s physiological (e.g., age, maturity) and psychological (e.g., mood, stress level, personality) characteristics affect competence (Cooley & Roach, 1984). These factors can help and hinder you when you try to apply the knowledge you have learned to actual communication behaviors. For example, you might know strategies for being an effective speaker, but public speaking anxiety that kicks in when you get in front of the audience may prevent you from fully putting that knowledge into practice. So to develop our ability to use communication skills, we need to practice these skills over time!

The third part of the definition we will unpack is the ability to adapt to various contexts. What is competent or not varies based on social and cultural context, which makes it impossible to have only one standard for what counts as communication competence (Cooley & Roach, 1984). Social variables such as status and power affect competence. In a social situation where one person—say, a supervisor—has more power than another—for example, his or her employee—then the supervisor is typically the one who sets the standard for competence. Cultural variables such as race and nationality also affect competence. A Taiwanese woman who speaks English as her second language may be praised for her competence in the English language in her home country but be viewed as less competent in the United States because of her accent. In summary, although we have a clear definition of communication competence, there are no definitions for how to be competent in any given situation, since competence varies at the individual, social, and cultural levels.

Steps in Developing Competence

Knowing the dimensions of competence is an important first step toward developing competence. Everyone reading this book already has some experience with and knowledge about communication. After all, you’ve spent many years explicitly and implicitly learning to communicate. For example, we are explicitly taught the verbal codes we use to communicate. On the other hand, although there are numerous rules and norms associated with nonverbal communication, we rarely receive explicit instruction on how to do it. Instead, we learn by observing others and through trial and error with our own nonverbal communication. Competence obviously involves verbal and nonverbal elements, but it also applies to many situations and contexts. Communication competence is needed in order to understand communication ethics, to develop cultural awareness, to use computer-mediated communication, and to think critically. Competence involves knowledge, motivation, and skills. It’s not enough to know what good communication consists of; you must also have the motivation to reflect on and better your communication and the skills needed to do so.

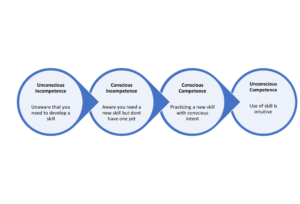

Since communication competence is a dynamic and evolving process, we will continuously have competencies we are skilled in and areas where we can improve. The development of communication competence occurs over time and through a series of four stages (Hargie, 2011).

Stage 1: Unconscious Incompetence. Before you have built up a rich cognitive knowledge base of communication concepts and practiced and reflected on skills in a particular area, you may exhibit unconscious incompetence, which means you are not even aware that you are communicating in an incompetent manner.

Stage 2: Conscious Incompetence. Once you learn more about communication and have a vocabulary to identify concepts, you may find yourself exhibiting conscious incompetence. This is where you know what you should be doing, and you realize that you’re not doing it as well as you could.

Stage 3: Conscious Competence. As your skills increase you may advance to conscious competence, meaning that you know you are communicating well in the moment, which will add to your bank of experiences to draw from in future interactions.

Stage 4: Unconscious Competence. When you reach the stage of unconscious competence, you just communicate successfully without having to think about being competent. Just because you reach the stage of unconscious competence in one area or with one person does not mean you will always stay there. We are faced with new communication encounters regularly, and although we may be able to draw on the communication skills we have learned about and developed, a new situation or encounter may affect our level of competence.

In some introductory communication classes students think that Communication Studies professors must have high levels of communication competence. While knowing concepts, definitions and research within the field is a start, it doesn’t mean professor always put this information to good use. We are all imperfect and fallible, and if we expect to be perfect communicators after studying this, then we’re setting ourselves up for failure. However, what we can all make mental notes and reflect on how our interactions with other are going. This is known as being a mindful communicator.

Mindful Communicator

One way to progress toward communication competence is to become a more mindful communicator. A mindful communicator actively and fluidly processes information, is sensitive to communication contexts and multiple perspectives, and is able to adapt to novel communication situations (Burgoon, Berger, & Waldron, 2000). Mindful communication involves processing information about the other person and about how we are feeling during the interaction. It allows us to form the truest meaning of the message as we form a deeper understanding of the other person and ourselves. Various communication behaviors can signal that we are communicating mindfully. For example, asking a child to paraphrase their understanding of the instructions you just gave them shows that you are aware that verbal messages are not always clear, that people do not always listen actively, and that people often do not speak up when they are unsure of instructions for fear of appearing incompetent or embarrassing themselves. Some communication behaviors indicate that we are not communicating mindfully, such as withdrawing from a romantic partner or engaging in passive-aggressive behavior during a period of interpersonal conflict. Most of us know that such behaviors lead to predictable and avoidable conflict cycles, yet we are all guilty of them.

Becoming a more mindful communicator has many benefits, including in the simplest of communication interactions—a conversation. Mindful communication during conversations can help build and maintain positive relationships, be key to accomplishing goals in our personal and professional lives, or serve to simply learn something that we can apply in many ways. In a Tedx Talks (2015) presentation, Celeste Headlee, an award-winning interviewer, proposes that there are 10 rules to having a good conversation:

- Stop multitasking.

- Assume you have something to learn.

- Use open-ended questions.

- Go with the flow. Allow your own thoughts to enter, then let them go. Remain focused on the speaker’s messages.

- If you don’t know, say you don’t know.

- Don’t equate your experience with theirs. Let the moment be about them.

- Try not to repeat yourself. It’s boring and condescending.

- Don’t get bogged down in the details. Focus on learning about the person, and them learning about you.

- Listen. When we are speaking, we are not learning.

- Be brief—short enough to retain interest, long enough to cover the subject.

Headlee suggests that the key to mindful communication in conversations is remaining interested in others. This is just the beginning of our conversation about communication competence and mindful communication. We will revisit these concepts throughout the course.

Key Takeaways

- Communication competence refers to the knowledge of effective and appropriate communication patterns and the ability to use and adapt that knowledge in various contexts.

- To be a competent communicator, you should have cognitive knowledge about communication based on observation and instruction; practice skill acquisition; and understand that individual, social, and cultural contexts affect competence; and be able to adapt to those various contexts.

- Levels of communication competence include unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, and unconscious competence.

- In order to develop communication competence, you must become a more mindful communicator and a higher self-monitor.

Exercises

- Consider a former teacher, guardian, coach, or boss that you considered good at communication. What made them a good communicator? If you could adopt just one of their communication skills, what would it be and why?

- Would you consider yourself a competent communicator? Do you see examples of the four stages in your life? Explain your answer using examples.

- Do you communicate mindfully? Explain your answer using examples.

- What motivates you to become a competent communicator?

- Create one to three personal goals that would move you towards communication competence.

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been reproduced or adapted from the following resource: Introduction to Communications Copyright © 2023 by NorQuest College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.