Chapter 3: Verbal Communication

3.2 Language: Expressive & Relational

Learning Objectives

- Identify and discuss the four main types of linguistic expressions.

- Explain how language is relational, bringing us together and apart.

Language Is Expressive

Verbal communication helps us meet various needs through our ability to express ourselves. In terms of instrumental needs, we use verbal communication to ask questions that provide us with specific information. We also use verbal communication to describe things, people, and ideas. It is also through our verbal expressions that our personal relationships are formed. At its essence, language is expressive. help us communicate our observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs[1].

1. Expressing Observations

When we express observations, we report on the sensory information we are taking or have taken in. As we learned in Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception” on perception, observation and description occur in the first step of the perception-checking process. When you are trying to make sense of an experience, expressing observations in a descriptive rather than evaluative way can lessen defensiveness, which facilitates competent communication.

2. Expressing Thoughts

When we express thoughts, we draw conclusions based on what we have experienced. In the perception process, this is similar to the interpretation step. We take various observations and evaluate and interpret them to assign them meaning (a conclusion). Whereas our observations are based on sensory information (what we saw, what we read, what we heard), thoughts are connected to our beliefs (what we think is true/false), attitudes (what we like and dislike), and values (what we think is right/wrong or good/bad). Jury members are expected to express thoughts based on reported observations to help reach a conclusion about someone’s guilt or innocence. A juror might express the following thought: “The neighbor who saw the car leaving the night of the crime seemed credible. And the defendant seemed to have a shady past—I think he’s trying to hide something.” Sometimes people intentionally or unintentionally express thoughts as if they were feelings. For example, when people say, “I feel like you’re too strict with your attendance policy,” they aren’t really expressing a feeling; they are expressing a judgment about the other person (a thought).

3. Expressing Feelings

When we express feelings, we communicate our emotions. Expressing feelings is a difficult part of verbal communication, because there are many social norms about how, why, when, where, and to whom we express our emotions. Norms for emotional expression also vary based on nationality and other cultural identities and characteristics such as age and gender. In terms of age, young children are typically freer to express positive and negative emotions in public. Gendered elements intersect with age as boys grow older and are socialized into a norm of emotional restraint. Although individual men vary in the degree to which they are emotionally expressive, there is still a prevailing social norm that encourages and even expects women to be more emotionally expressive than men.

Expressing feelings can be uncomfortable for those listening. Some people are generally not good at or comfortable with receiving and processing other people’s feelings. Even those with good empathetic listening skills can be positively or negatively affected by others emotions. Expressions of anger can be especially difficult to manage because they represent a threat to the face and self-esteem of others. Despite the fact that expressing feelings is more complicated than other forms of expression, emotion sharing is an important part of how we create social bonds and empathize with others, and it can be improved.

In order to verbally express our emotions, it is important that we develop an emotional vocabulary. The more specific we can be when we are verbally communicating our emotions, the less ambiguous our emotions will be for the person decoding our message. As we expand our emotional vocabulary, we are able to convey the intensity of the emotion we’re feeling whether it is mild, moderate, or intense. For example, happy is mild, delighted is moderate, and ecstatic is intense; ignored is mild, rejected is moderate, and abandoned is intense.[2]

In a time when so much of our communication is electronically mediated, it is likely that we will communicate emotions through the written word in an e-mail, text, or instant message. We may also still use pen and paper when sending someone a thank-you note, a birthday card, or a sympathy card. Communicating emotions through the written (or typed) word can have advantages such as time to compose your thoughts and convey the details of what you’re feeling. There are also disadvantages in that important context and nonverbal communication can’t be included. Things like facial expressions and tone of voice offer much insight into emotions that may not be expressed verbally. There is also a lack of immediate feedback. Sometimes people respond immediately to a text or e-mail, but think about how frustrating it is when you text someone and they don’t get back to you right away. If you’re in need of emotional support or want validation of an emotional message you just sent, waiting for a response could end up negatively affecting your emotional state.

4. Expressing Needs

When we express needs, we are communicating in an instrumental way to help us get things done. Since we almost always know our needs more than others do, it’s important for us to be able to convey those needs to others. Expressing needs can help us get a project done at work or help us navigate the changes of a long-term romantic partnership. Not expressing needs can lead to feelings of abandonment, frustration, or resentment. For example, if one romantic partner expresses the following thought “I think we’re moving too quickly in our relationship” but doesn’t also express a need, the other person in the relationship doesn’t have a guide for what to do in response to the expressed thought. Stating, “I need to spend some time with my hometown friends this weekend. Would you mind if I went home by myself?” would likely make the expression more effective. Be cautious of letting evaluations or judgments sneak into your expressions of need. Saying “I need you to stop suffocating me!” really expresses a thought-feeling mixture more than a need.

Table 3.1 Four Types of Verbal Expressions

| Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Observation | Report of sensory experiences or memories | “Pauline asked me to bring this file to you.” |

| Thought | Conclusion about or judgment of experiences and observations | “Students today have much less respect for authority.” |

| Feeling | Communicating emotions | “I feel at peace when we’re together.” |

| Need | Stating wants or requesting help or support | “I’m saving money for summer vacation. Is it OK if we skip our regular night out this week?” |

Source: Adapted from Matthew McKay, Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Messages: Communication Skills Book, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 34–36.

“Getting Plugged In”

Is “Textese” Hurting Our Verbal Communication?

Textese, also called text-message-ese and txt talk, among other things, has been called a “new dialect” of English that mixes letters and numbers, abbreviates words, and drops vowels and punctuation to create concise words and statements. Although this “dialect” has primarily been relegated to the screens of smartphones and other text-capable devices, it has slowly been creeping into our spoken language.[3] Some critics say textese is “destroying” language by “pillaging punctuation” and “savaging our sentences.”[4] A relatively straightforward tks for “thanks” or u for “you” has now given way to textese sentences like IMHO U R GR8. If you translated that into “In my humble opinion, you are great,” then you are fluent in textese. Although teachers and parents seem convinced that this type of communicating will eventually turn our language into emoticons and abbreviations, some scholars aren’t. David Crystal, a well-known language expert, says that such changes to the English language aren’t new and that texting can actually have positive effects. He points out that Shakespeare also abbreviated many words, played with the rules of language, and made up several thousand words, and he is not considered an abuser of language. He also cites research that found, using experimental data, that children who texted more scored higher on reading and vocabulary tests. Crystal points out that in order to play with language, you must first have some understanding of the rules of language.[5]

- What effects, if any, do you think textese has had on your non-text-message communication?

- Overall do you think textese and other forms of computer-mediated communication have affected our communication? Try to identify one potential positive and negative influence that textese has had on our verbal communication.

Language Is Relational: It Can Bring Us Together & Pull Us Apart

We use verbal communication to initiate, maintain, and terminate our interpersonal relationships. The first few exchanges with a potential romantic partner or friend help us size the other person up and figure out if we want to pursue a relationship or not. We then use verbal communication to remind others how we feel about them and to check in with them—engaging in relationship maintenance through language use. When negative feelings arrive and persist, or for many other reasons, we often use verbal communication to end a relationship.

Whether intentionally or unintentionally, our use of words like I, you, we, our, and us affect our relationships. “We language” includes the words we, our, and us and can be used to promote a feeling of inclusiveness. “I language” can be useful when expressing thoughts, needs, and feelings because it leads us to “own” our expressions and avoid the tendency to mistakenly attribute the cause of our thoughts, needs, and feelings to others. Communicating emotions using “I language” may also facilitate emotion sharing by not making our conversational partner feel at fault or defensive. For example, instead of saying, “You’re making me crazy!” you could say, “I’m starting to feel really anxious because we can’t make a decision about this.” Conversely, “you language” can lead people to become defensive and feel attacked, which could be divisive and result in feelings of interpersonal separation.

Defensive behavior is defined as that behavior which occurs when an individual perceives threat or anticipates threat in the group. The person who behaves defensively, even though he or she also gives some attention to the common task, devotes an appreciable portion of energy to defending himself or herself. Besides talking about the topic, he/she thinks about how they appear to others, how they may be seen more favorably, how they may win, dominate, impress or escape punishment, and/or how they may avoid or mitigate a perceived attack.

Such inner feelings and outward acts tend to create similarly defensive postures in others; and, if unchecked, the ensuing circular response becomes increasingly destructive. Defensive behavior, in short, engenders defensive listening, and this in turn produces postural, facial and verbal cues which raise the defense level of the original communicator.

Defense arousal prevents the listener from concentrating upon the message. Not only do defensive communicators send off multiple value, motive and affect cues, but also defensive recipients distort what they receive. As a person becomes more and more defensive, he or she becomes less and less able to perceive accurately the motives, the values and the emotions of the sender. Defensive behaviors have been correlated positively with losses in efficiency in communication.

The converse, moreover, also is true. The more “supportive” or defense-reductive the climate, the less the receiver reads into the communication distorted loadings which arise from projections of his own anxieties, motives and concerns. As defenses are reduced, the receivers become better able to concentrate upon the structure, the content and the cognitive meanings of the message.

Categories of Defensive and Supportive Communications

Jack Gibb developed six pairs of defensive and supportive categories presented below. Behavior which a listener perceives as possessing any of the characteristics listed in the left-hand column arouses defensiveness, whereas that which he interprets as having any of the qualities designated as supportive reduces defensive feelings. The degree to which these reactions occur depends upon the person’s level of defensiveness and upon the general climate in the group at the time.

Gibb’s Categories of Behavior Characteristic of Supportive and Defensive Climates

| Defensive Climates | Supportive Climates |

| 1. Evaluation | 1. Description |

| 2. Control | 2. Problem Orientation |

| 3. Strategy | 3. Spontaneity |

| 4. Neutrality | 4. Empathy |

| 5. Superiority | 5. Equality |

| 6. Certainty | 6. Provisionalism |

Evaluation and Description

Speech or other behavior which appears evaluative increases defensiveness. If by expression, manner of speech, tone of voice or verbal content the sender seems to be evaluating or judging the listener, the receiver goes on guard. Of course, other factors may inhibit the reaction. If the listener thought that the speaker regarded him/her as an equal and was being open and spontaneous, for example, the evaluativeness in a message would be neutralized and perhaps not even perceived. This same principle applies equally to the other five categories of potentially defense-producing climates. These six sets are interactive.

Because our attitudes toward other persons are frequently, and often necessarily, evaluative, expressions which the defensive person will regard as nonjudgmental are hard to frame. Even the simplest question usually conveys the answer that the sender wishes or implies the response that would fit into his or her value system. A mother, for example, immediately following an earth tremor that shook the house, sought for her small son with the question, “Bobby, where are you?” The timid and plaintive “Mommy, I didn’t do it” indicated how Bobby’s chronic mild defensiveness predisposed him to react with a projection of his own guilt and in the context of his chronic assumption that questions are full of accusation.

Anyone who has attempted to train professionals to use information-seeking speech with neutral affect appreciates how difficult it is to teach a person to say even the simple “who did that?” without being seen as accusing. Speech is so frequently judgmental that there is a reality base for the defensive interpretations which are so common.

When insecure, group members are particularly likely to place blame, to see others as fitting into categories of good or bad, to make moral judgments of their colleagues and to question the value, motive and affect loadings of the speech which they hear. Since value loadings imply a judgment of others, a belief that the standards of the speaker differ from his or her own causes the listener to become defensive.

Descriptive speech, in contrast to that which is evaluative, tends to arouse a minimum of uneasiness. Speech acts in which the listener perceives as genuine requests for information or as material with neutral loadings is descriptive. Specifically, presentation of feelings, events, perceptions or processes which do not ask or imply that the receiver change behavior or attitude are minimally defense producing. On a side note, one can often tell from the opening words in a news article which side the newspaper’s editorial policy favors.

Control and Problem Orientation

Speech which is used to control the listener evokes resistance. In most of our social intercourse, someone is trying to do something to someone else—to change an attitude, to influence behavior, or to restrict the field of activity. The degree to which attempts to control produce defensiveness depends upon the openness of the effort, for a suspicion that hidden motives exist heightens resistance. For this reason, attempts of nondirective therapists and progressive educators to refrain from imposing a set of values, a point of view or a problem solution upon the receivers meet with many barriers. Since the norm is control, noncontrollers must earn the perceptions that their efforts have no hidden motives. A bombardment of persuasive “messages” in the fields of politics, education, special causes, advertising, religion, medicine, industrial relations and guidance has bred cynical and paranoid responses in listeners.

Implicit in all attempts to alter another person is the assumption by the change agent that the person to be altered is inadequate. That the speaker secretly views the listener as ignorant, unable to make his or her own decisions, uninformed, immature, unwise, or possessed of wrong or inadequate attitudes is a subconscious perception which gives the latter a valid base for defensive reactions.

Strategy and Spontaneity

When the sender is perceived as engaged in a stratagem involving ambiguous and multiple motivations, the receiver becomes defensive. No one wishes to be a guinea pig, a role player, or an impressed actor, and no one likes to be the victim of some hidden motivation. That which is concealed, also, may appear larger than it really is with the degree of defensiveness of the listener determining the perceived size of the element. The intense reaction of the reading audience to the material in The Hidden Persuaders indicates the prevalence of defensive reactions to multiple motivations behind strategy. Group members who are seen as “taking a role” as feigning emotion, as toying with their colleagues, as withholding information or as having special sources of data are especially resented. One participant once complained that another was “using a listening technique” on him!

A large part of the adverse reaction to much of the so-called human relations training is a feeling against what are perceived as gimmicks and tricks to fool or to “involve” people, to make a person think he or she is making their own decision, or to make the listener feel that the sender is genuinely interested in him or her as a person. Particularly violent reactions occur when it appears that someone is trying to make a stratagem appear spontaneous. One person reported a boss who incurred resentment by habitually using the gimmick of “spontaneously” looking at his watch and saying “my gosh, look at the time—I must run to an appointment.” The belief was that the boss would create less irritation by honestly asking to be excused.

The aversion to deceit may account for one’s resistance to politicians who are suspected of behind-the-scenes planning to get one’s vote, to psychologists whose listening apparently is motivated by more than the manifest or content-level interest in one’s behavior, or the sophisticated, smooth, or clever person whose one-upmanship is marked with guile. In training groups the role-flexible person frequently is resented because his or her changes in behavior are perceived as strategic maneuvers.

In contrast, behavior that appears to be spontaneous and free of deception is defense reductive. If the communicator is seen as having a clean id, as having uncomplicated motivations, as being straightforward and honest, as behaving spontaneously in response to the situation, he or she is likely to arouse minimal defensiveness.

Neutrality and Empathy

When neutrality in speech appears to the listener to indicate a lack of concern for his welfare, he becomes defensive. Group members usually desire to be perceived as valued persons, as individuals with special worth, and as objects of concern and affection. The clinical, detached, person-is-an-object-study attitude on the part of many psychologist-trainers is resented by group members. Speech with low affect that communicates little warmth or caring is in such contrast with the affect-laden speech in social situations that it sometimes communicates rejection.

Communication that conveys empathy for the feelings and respect for the worth of the listener, however, is particularly supportive and defense reductive. Reassurance results when a message indicates that the speaker identifies himself or herself with the listener’s problems, shares her feelings, and accepts her emotional reactions at face value. Abortive efforts to deny the legitimacy of the receiver’s emotions by assuring the receiver that she need not feel badly, that she should not feel rejected, or that she is overly anxious, although often intended as support giving, may impress the listener as lack of acceptance. The combination of understanding and empathizing with the other person’s emotions with no accompanying effort to change him or her is supportive at a high level.

The importance of gestural behavior cues in communicating empathy should be mentioned. Apparently spontaneous facial and bodily evidences of concern are often interpreted as especially valid evidence of deep-level acceptance.

Superiority and Equality

When a person communicates to another that he or she feels superior in position, power, wealth, intellectual ability, physical characteristics, or other ways, she or he arouses defensiveness. Here, as with other sources of disturbance, whatever arouses feelings of inadequacy causes the listener to center upon the affect loading of the statement rather than upon the cognitive elements. The receiver then reacts by not hearing the message, by forgetting it, by competing with the sender, or by becoming jealous of him or her.

The person who is perceived as feeling superior communicates that he or she is not willing to enter into a shared problem-solving relationship, that he or she probably does not desire feedback, that he or she does not require help, and/or that he or she will be likely to try to reduce the power, the status, or the worth of the receiver.

Many ways exist for creating the atmosphere that the sender feels himself or herself equal to the listener. Defenses are reduced when one perceives the sender as being willing to enter into participative planning with mutual trust and respect. Differences in talent, ability, worth, appearance, status and power often exist, but the low defense communicator seems to attach little importance to these distinctions.

Certainty and Provisionalism

The effects of dogmatism in producing defensiveness are well known. Those who seem to know the answers, to require no additional data, and to regard themselves as teachers rather than as co-workers tend to put others on guard. Moreover, listeners often perceive manifest expressions of certainty as connoting inward feelings of inferiority. They see the dogmatic individual as needing to be right, as wanting to win an argument rather than solve a problem and as seeing his or her ideas as truths to be defended. This kind of behavior often is associated with acts which others regarded as attempts to exercise control. People who are right seem to have low tolerance for members who are “wrong”—i.e., who do not agree with the sender.

One reduces the defensiveness of the listener when one communicates that one is willing to experiment with one’s own behavior, attitudes and ideas. The person who appears to be taking provisional attitudes, to be investigating issues rather than taking sides on them, to be problem solving rather than doubting, and to be willing to experiment and explore tends to communicate that the listener may have some control over the shared quest or the investigation of the ideas. If a person is genuinely searching for information and data, he or she does not resent help or company along the way.

Aside from the specific words that we use, the frequency of communication impacts relationships. Of course, the content of what is said is important, but research shows that romantic partners who communicate frequently with each other and with mutual friends and family members experience less stress and uncertainty in their relationship and are more likely to stay together.[6]When frequent communication combines with, which are messages communicated in an open, honest, and nonconfrontational way, people are sure to come together.

Key Takeaways

- Language helps us express observations (reports on sensory information), thoughts (conclusions and judgments based on observations or ideas), feelings, and needs.

- Language is powerful in that it expresses our identities through labels used by and on us, affects our credibility based on how we support our ideas, serves as a means of control, and performs actions when spoken by certain people in certain contexts.

- The productivity and limitlessness of language creates the possibility for countless word games and humorous uses of language.

- Language is dynamic, meaning it is always changing through the addition of neologisms, new words or old words with new meaning, and the creation of slang.

- Language is relational and can be used to bring people together through a shared reality but can separate people through unsupportive and divisive messages.

Exercises

- Based on what you are doing and how you are feeling at this moment, write one of each of the four types of expressions—an observation, a thought, a feeling, and a need.

- Getting integrated: A key function of verbal communication is expressing our identities. Identify labels or other words that are important for your identity in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic. (Examples include honors student for academic, trainee for professional, girlfriend for personal, and independent for civic.)

- Review the types of unsupportive messages discussed earlier. Which of them do you think has the potential to separate people the most? Why? Which one do you have the most difficulty avoiding (directing toward others)? Why?

- Matthew McKay, Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Messages: Communication Skills Book, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 34–36. ↵

- Owen Hargie, Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 166. ↵

- Lily Huang, “Technology: Textese May Be the Death of English,” Newsweek, August 2011, 8. ↵

- John Humphrys, “I h8 txt msgs: How Texting Is Wrecking Our Language,” Daily Mail, September 24, 2007, accessed June 7, 2012. ↵

- Lily Huang, “Technology: Textese May Be the Death of English,” Newsweek, August 2011, 8. ↵

- Steven McCornack, Reflect and Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal Communication (Boston, MA: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2007), 237. ↵

Language that helps us communicate our observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss factors that can impact language clarity.

- Identify strategies for using language ethically.

Have you ever gotten lost because someone gave you directions that didn’t make sense to you? Have you ever puzzled over the instructions for how to put something like a bookshelf or grill together? When people don’t use words well, there are consequences that range from mild annoyance to legal actions. When people do use words well, they can be inspiring and make us better people. In this section, we will learn how to use words well by using words clearly, using words affectively, and using words ethically.

Using Words Clearly

The level of clarity with which we speak varies depending on whom we talk to, the situation we’re in, and our own intentions and motives. We sometimes make a deliberate effort to speak as clearly as possible. We can indicate this concern for clarity nonverbally by slowing our rate and increasing our volume or verbally by saying, “Frankly…” or “Let me be clear…” Sometimes it can be difficult to speak clearly—for example, when we are speaking about something with which we are unfamiliar. Emotions and distractions can also interfere with our clarity. Being aware of the varying levels of abstraction within language can help us create clearer and more “whole” messages.

Level of Abstraction

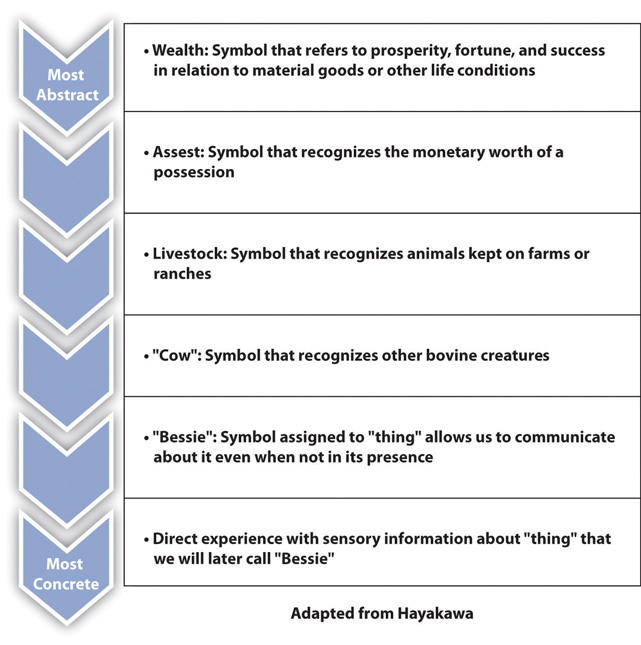

The ladder of abstraction is a model used to illustrate how language can range from concrete to abstract. As we follow a concept up the ladder of abstraction, more and more of the “essence” of the original object is lost or left out, which leaves more room for interpretation, which can lead to misunderstanding. This process of abstracting, of leaving things out, allows us to communicate more effectively because it serves as a shorthand that keeps us from having a completely unmanageable language filled with millions of words—each referring to one specific thing.[1] But it requires us to use context and often other words to generate shared meaning. Some words are more directly related to a concept or idea than others. If I asked you to go take a picture of a book, you could do that. If I asked you to go and take a picture of “work,” you couldn’t because work is an abstract word that was developed to refer to any number of possibilities from the act of writing a book, to repairing an air conditioner, to fertilizing an organic garden. You could take a picture of any of those things, but you can’t take a picture of “work.”

You can see the semanticist S. I. Hayakawa’s classic example of the abstraction ladder with “Bessie the cow” in Figure 3.2 "Ladder of Abstraction".[2] At the lowest level, we have something that is very concrete. At this level we are actually in the moment of experiencing the stimuli that is coming in through our senses. We perceive the actual “thing,” which is the “cow” in front of us (either in person or as an image). This is concrete, because it is unmediated, meaning it is actually the moment of experience. As we move up a level, we give the experience a name—we are looking at “Bessie.” So now, instead of the direct experience with the “thing” in front of us, we have given the thing a name, which takes us one step away from the direct experience to the use of a more abstract symbol. Now we can talk and think about Bessie even when we aren’t directly experiencing her. At the next level, the word cow now lumps Bessie in with other bovine creatures that share similar characteristics. As we go on up the ladder, cow becomes livestock, livestock becomes an asset, and then an asset becomes wealth. Note that it becomes increasingly difficult to define the meaning of the symbol as we go up the ladder and how with each step we lose more of the characteristics of the original concrete experience.

When shared referents are important, we should try to use language that is lower on the ladder of abstraction. Being intentionally concrete is useful when giving directions, for example, and can help prevent misunderstanding. We sometimes intentionally use abstract language. Since abstract language is often unclear or vague, we can use it as a means of testing out a potential topic (like asking a favor), offering negative feedback indirectly (to avoid hurting someone’s feelings or to hint), or avoiding the specifics of a topic.

Connotative Meaning and Relative Language

As we learned earlier, denotative definitions are those found in the dictionary—the official or agreed-on definition. Since definitions are composed of other words, people who compile dictionaries take for granted that there is a certain amount of familiarity with the words they use to define another word—otherwise we would just be going in circles. In addition to denotative definitions, words also have connotative definitions, or meanings. The connotative meaning of a word or utterances, is the personal meaning ascribed to it by the various participants. For example, we might all be able to agree on a denotative definition of "early" (an occurrence before a pre-determined time), but what it means to "be early" may vary. For example, if you were let out of class 5 minutes before the formally established end time, would you be likely to tell your friends and family members know you got out of class "early" today? Would you need to be let out 10, 15, 20 minutes before the end of class for it to feel "early" for you? Thus, what constitutes "early" in this situation is the connotative meaning of the participants. One challenge related to this is referred to as relative language. Relative language is that which takes on it's meaning based on comparisons. Early, late, easy, cheap, fast, big...all of these words have meanings that are relative depending on what one compares them to.

Jargon and Slang

Jargon refers to specialized words used by a certain group or profession. Since jargon is specialized, it is often difficult to relate to a diverse audience and should therefore be limited when speaking to people from outside the group—or at least be clearly defined when it is used. Slang is informal language, that changes and is often associated with a particular social group or context. Examples of slang include "rad", "chill" and "lit"; whereas examples of jargon are "receivables" (accounting), "prophylactic" (medicine), and "haptics" (communication studies).

Creating Whole Messages

Earlier we learned about the four types of expressions, which are observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs. Whole messages include all the relevant types of expressions needed to most effectively communicate in a given situation, including what you see, what you think, what you feel, and what you need. Partial messages are missing a relevant type of expression and can lead to misunderstanding and conflict. Whole messages help keep lines of communication open, which can help build solid relationships. On the other hand, people can often figure out a message is partial even if they can’t readily identify what is left out. For example, if Roscoe says to Rachel, “I don’t trust Bob anymore,” Rachel may be turned off or angered by Roscoe’s conclusion (an expression of thought) about their mutual friend. However, if Roscoe recounted his observation of Bob’s behavior, how that behavior made him feel, and what he needs from Rachel in this situation, she will be better able to respond.

While partial messages lack relevant expressions needed to clearly communicate, contaminated messages include mixed or misleading expressions. For example, if Alyssa says to her college-aged daughter, “It looks like you wasted another semester,” she has contaminated observations, feelings, and thoughts. Although the message appears to be an observation, there are underlying messages that are better brought to the surface. To decontaminate her message, and make it more whole and less alienating, Alyssa could more clearly express herself by saying, “Your dad and I talked, and he said you told him you failed your sociology class and are thinking about changing your major” (observation). “I think you’re hurting your chances of graduating on time and getting started on your career” (thought). “I feel anxious because you and I are both taking out loans to pay for your education” (feeling).

Messages in which needs are contaminated with observations or feelings can be confusing. For example, if Shea says to Duste, “You’re so lucky that you don’t have to worry about losing your scholarship over this stupid biology final,” it seems like he’s expressing an observation, but it’s really a thought, with an underlying feeling and need. To make the message more whole, Shea could bring the need and feeling to the surface: “I noticed you did really well on the last exam in our biology class” (observation). “I’m really stressed about the exam next week and the possibility of losing my scholarship if I fail it” (feeling). “Would you be willing to put together a study group with me?” (need). More clarity in language is important, but as we already know, communication isn’t just about exchanging information—the words we use also influence our emotions and relationships.

Evocative Language

Vivid language captures people’s attention and their imagination by conveying emotions and action. Think of the array of mental images that a poem or a well-told story from a friend can conjure up. Evocative language can also lead us to have physical reactions. Words like shiver and heartbroken can lead people to remember previous physical sensations related to the word. As a speaker, there may be times when evoking a positive or negative reaction could be beneficial. Evoking a sense of calm could help you talk a friend through troubling health news. Evoking a sense of agitation and anger could help you motivate an audience to action. When we are conversing with a friend or speaking to an audience, we are primarily engaging others’ visual and auditory senses. Evocative language can help your conversational partner or audience members feel, smell, or taste something as well as hear it and see it. Good writers know how to use words effectively and affectively. A well-written story, whether it is a book or screenplay, will contain all the previous elements. The rich fantasy worlds conceived in Star Trek, The Lord of the Rings, Twilight, and Harry Potter show the power of figurative and evocative language to capture our attention and our imagination.

Some words are so evocative that their usage violates the social norms of appropriate conversations. Although we could use such words to intentionally shock people, we can also use euphemisms, or less evocative synonyms for or indirect references to words or ideas that are deemed inappropriate to discuss directly. We have many euphemisms for things like excretory acts, sex, and death.[3] While euphemisms can be socially useful and creative, they can also lead to misunderstanding and problems in cases where more direct communication is warranted despite social conventions.

Polarizing Language (Static Evaluation)

Philosophers of language have long noted our tendency to verbally represent the world in very narrow ways when we feel threatened.[4] This misrepresents reality and closes off dialogue. Although in our everyday talk we describe things in nuanced and measured ways, quarrels and controversies often narrow our vision, which is reflected in our vocabulary. In order to maintain a civil discourse in which people interact ethically and competently, it has been suggested that we keep an open mind and an open vocabulary.

One feature of communicative incivility is polarizing language, which refers to language that presents people, ideas, or situations as polar opposites. Such language exaggerates differences and overgeneralizes. Things aren’t simply black or white, right or wrong, or good or bad. Being able to only see two values and clearly accepting one and rejecting another doesn’t indicate sophisticated or critical thinking. We don’t have to accept every viewpoint as right and valid, and we can still hold strongly to our own beliefs and defend them without ignoring other possibilities or rejecting or alienating others. A citizen who says, “All cops are corrupt,” is just as wrong as the cop who says, “All drug users are scum.” In avoiding polarizing language we keep a more open mind, which may lead us to learn something new. A citizen may have a personal story about a negative encounter with a police officer that could enlighten us on his or her perspective, but the statement also falsely overgeneralizes that experience. Avoiding polarizing language can help us avoid polarized thinking, and the new information we learn may allow us to better understand and advocate for our position. Avoiding sweeping generalizations allows us to speak more clearly and hopefully avoid defensive reactions from others that result from such blanket statements.

Swearing

Scholars have identified two main types of swearing: social swearing and annoyance swearing. People engage in social swearing to create social bonds or for impression management (to seem cool or attractive). This type of swearing is typically viewed as male dominated, but some research studies have shown that the differences in frequency and use of swearing by men and women aren’t as vast as perceived. Nevertheless, there is generally more of a social taboo against women swearing than men, but as you already know, communication is contextual. Annoyance swearing provides a sense of relief, as people use it to manage stress and tension, which can be a preferred alternative to physical aggression. In some cases, swearing can be cathartic, allowing a person to release emotions that might otherwise lead to more aggressive or violent actions.

In the past few decades, the amount of profanity used in regular conversations and on television shows and movies has increased. This rise has been connected to a variety of factors, including increasing social informality since the 1960s and a decrease in the centrality of traditional/conservative religious views in many Western cultures. As a result of these changes, the shock value that swearing once had is lessening, and this desensitization has contributed to its spread. You have probably even noticed in your lifetime that the amount of swearing on television has increased, and in June of 2012 the Supreme Court stripped the Federal Communications Commission of some of its authority to fine broadcasters for obscenities.There has also been a reaction, or backlash, to this spread, which is most publicly evidenced by the website, book, and other materials produced by the Cuss Control Academy. Although swearing is often viewed as negative and uncivil, some scholars argue for its positive effects. Specifically, swearing can help people to better express their feelings and to develop social bonds. In fact, swearing is typically associated more with the emotional part of the brain than the verbal part of the brain, as evidenced by people who suffer trauma to the verbal part of their brain and lose all other language function but are still able to swear.

Fact-Inference-Judgments/Opinions

The complexity of our verbal language system allows us to present inferences as facts and mask judgments within seemingly objective or oblique language. As an ethical speaker and a critical listener, it is important to be able to distinguish between facts, inferences, and judgments. Inferences are conclusions based on thoughts or speculation, but not direct observation. Facts are conclusions based on direct observation or group consensus. Judgments are expressions of approval or disapproval that are subjective and not verifiable.

Linguists have noted that a frequent source of miscommunication is inference-fact confusion, or the misperception of an inference (conclusion based on limited information) as a fact (an observed or agreed-on observation). We can see the possibility for such confusion in the following example: If a student posts on a professor-rating site the statement “This professor grades unfairly and plays favorites,” then they are presenting an inference and a judgment that could easily be interpreted as a fact. Using some of the strategies discussed earlier for speaking clearly can help present information in a more ethical way—for example, by using concrete and descriptive language and owning emotions and thoughts through the use of “I language.” To help clarify the message and be more accountable, the student could say, “I worked for three days straight on my final paper and only got a C,” which we will assume is a statement of fact. This could then be followed up with “But my friend told me she only worked on hers the day before it was due and she got an A. I think that’s unfair and I feel like my efforts aren’t recognized by the professor.” Of the last two statements, the first states what may be a fact (note, however, that the information is secondhand rather than directly observed) and the second states an inferred conclusion and expresses an owned thought and feeling. Sometimes people don’t want to mark their statements as inferences because they want to believe them as facts. In this case, the student may have attributed her grade to the professor’s “unfairness” to cover up or avoid thoughts that her friend may be a better student in this subject area, a better writer, or a better student in general. Distinguishing between facts, inferences, and judgments, however, allows your listeners to better understand your message and judge the merits of it, which makes us more accountable and therefore more ethical speakers.

Key Takeaways

- The symbolic nature of language means that misunderstanding can easily occur when words and their definitions are abstract (far removed from the object or idea to which the symbol refers). The creation of whole messages, which contain relevant observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs, can help reduce misunderstandings.

- Affective language refers to language used to express a person’s feelings and create similar feelings in another person. Metaphor, simile, personification, and vivid language can evoke emotions in speaker and listener.

- Incivility occurs when people deviate from accepted social norms for communication and behavior and manifests in swearing and polarized language that casts people and ideas as opposites. People can reduce incivility by being more accountable for the short- and long-term effects of their communication.

Exercises

- Following the example in the ladder of abstraction, take a common word referring to an object (like bicycle or smartphone) and write its meaning, in your own words, at each step from most concrete to most abstract. Discuss how the meaning changes as the word/idea becomes more abstract and how the word becomes more difficult to define.

-

Decontaminate the following messages by rewriting them in a way that makes them whole (separate out each type of relevant expression). You can fill in details if needed to make your expressions more meaningful.

- “I feel like you can’t ever take me seriously.”

- “It looks like you’ve ruined another perfectly good relationship.”

- Find a famous speech (for example, at http://www.americanrhetoric.com) and identify components of figurative language. How do these elements add to the meaning of the speech?

- Getting integrated: Review the section on using words ethically. Identify a situation in which language could be used unethically in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic. Specifically tie your example to civility, polarizing language, swearing, or accountability.