Chapter 7: Types of Interpersonal Relatonships

7.1 Communication & Friends

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast different types of friendships.

- Describe Rawlins’ stages of friendship.

- Discuss how friendships change across the life span, from adolescence to later life.

- Explain how culture and gender influence friendships.

Do you consider all the people you are “friends” with on Facebook to be friends? What’s the difference, if any, between a “Facebook friend” and a real-world friend? Friendships, like other relationship forms, can be divided into categories. What’s the difference between a best friend, a good friend, and an old friend? What about work friends, school friends, and friends of the family? It’s likely that each of you reading this book has a different way of perceiving and categorizing your friendships. In this section, we will learn about the various ways we classify friends, the life cycle of friendships, and how gender affects friendships.

Defining and Classifying Friends

Friendships are voluntary interpersonal relationships between two people who are usually equals and who mutually influence one another.[1] Friendships are distinct from romantic relationships, family relationships, and acquaintances and are often described as more vulnerable relationships than others due to their voluntary nature, the availability of other friends, and the fact that they lack the social and institutional support of other relationships. The lack of official support for friendships is not universal, though. In rural parts of Thailand, for example, special friendships are recognized by a ceremony in which both parties swear devotion and loyalty to each other.[2] Even though we do not have a formal ritual to recognize friendship in the United States, in general, research shows that people have three main expectations for close friendships. A friend is someone you can talk to, someone you can depend on for help and emotional support, and someone you can participate in activities and have fun with.[3]

Although friendships vary across the life span, three types of friendships are common in adulthood: reciprocal, associative, and receptive.[4] Reciprocal friendships are solid interpersonal relationships between people who are equals with a shared sense of loyalty and commitment. These friendships are likely to develop over time and can withstand external changes such as geographic separation or fluctuations in other commitments such as work and childcare. Reciprocal friendships are what most people would consider the ideal for best friends. Associative friendships are mutually pleasurable relationships between acquaintances or associates that, although positive, lack the commitment of reciprocal friendships. These friendships are likely to be maintained out of convenience or to meet instrumental goals.

For example, a friendship may develop between two people who work out at the same gym. They may spend time with each other in this setting a few days a week for months or years, but their friendship might end if the gym closes or one person’s schedule changes. Receptive friendships include a status differential that makes the relationship asymmetrical. Unlike the other friendship types that are between peers, this relationship is more like that of a supervisor-subordinate or clergy-parishioner. In some cases, like a mentoring relationship, both parties can benefit from the relationship. In other cases, the relationship could quickly sour if the person with more authority begins to abuse it.

A relatively new type of friendship, at least in label, is the “friends with benefits” relationship. Friends with benefits (FWB) relationships have the closeness of a friendship and the sexual activity of a romantic partnership without the expectations of romantic commitment or labels.[5] FWB relationships are hybrids that combine characteristics of romantic and friend pairings, which produces some unique dynamics. In my conversations with students over the years, we have talked through some of the differences between friends, FWB, and hook-up partners, or what we termed “just benefits.” Hook-up or “just benefits” relationships do not carry the emotional connection typical in a friendship, may occur as one-night-stands or be regular things, and exist solely for the gratification and/or convenience of sexual activity. So why might people choose to have or avoid FWB relationships?

Various research studies have shown that half of the college students who participated have engaged in heterosexual FWB relationships.[6] Many who engage in FWB relationships have particular views on love and sex—namely, that sex can occur independently of love. Conversely, those who report no FWB relationships often cite religious, moral, or personal reasons for not doing so. Some who have reported FWB relationships note that they value the sexual activity with their friend, and many feel that it actually brings the relationship closer. Despite valuing the sexual activity, they also report fears that it will lead to hurt feelings or the dissolution of a friendship.[7] We must also consider gender differences and communication challenges in FWB relationships.

Gender biases must be considered when discussing heterosexual FWB relationships, given that women in most societies are judged more harshly than men for engaging in casual sex. But aside from dealing with the double standard that women face regarding their sexual activity, there aren’t many gender differences in how men and women engage in and perceive FWB relationships. So what communicative patterns are unique to the FWB relationship? Those who engage in FWB relationships have some unique communication challenges. For example, they may have difficulty with labels as they figure out whether they are friends, close friends, a little more than friends, and so on. Research participants currently involved in such a relationship reported that they have more commitment to the friendship than the sexual relationship. But does that mean they would give up the sexual aspect of the relationship to save the friendship? The answer is “no” according to the research study. Most participants reported that they would like the relationship to stay the same, followed closely by the hope that it would turn into a full romantic relationship[8] Just from this study, we can see that there is often a tension between action and labels. In addition, those in a FWB relationship often have to engage in privacy management as they decide who to tell and who not to tell about their relationship, given that some mutual friends are likely to find out and some may be critical of the relationship. Last, they may have to establish ground rules or guidelines for the relationship. Since many FWB relationships are not exclusive, meaning partners are open to having sex with other people, ground rules or guidelines may include discussions of safer-sex practices, disclosure of sexual partners, or periodic testing for sexually transmitted infections.

Rawlins’ Stages of Friendship[9]

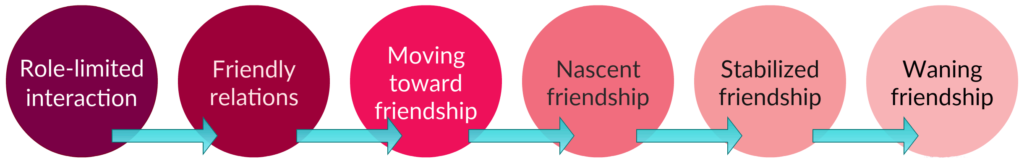

A common need we have as people is the need to feel connected with others. We experience great joy, adventure, and learning through our connection and interactions with others. The feeling of wanting to be part of a group and liked by others is natural. One way we meet our need for connection is through our friendships. Friendship has a different meaning to different people depending on age, gender, and cultural background. Common among all friendships is the fact that they are interpersonal relationships of choice. Throughout your life, you will engage in an ongoing process of developing friendships. Rawlins (1981) suggests that we develop our friendships through a series of six steps. While we may not follow these six steps in the exact order in all of our relationships, these steps help us understand how we develop friendships.

The first step in building friendships occurs through Role-Limited Interaction. In this step, we interact with others based on our social roles. For example, when you meet a new person in your class, the interaction centers around your role as “student”. The communication is characterized by a focus on superficial, rather than personal topics. In this step, we engage in limited self-disclosure and rely on scripts and stereotypes. When two first-time freshmen meet in an introductory course, they start up a conversation and interact according to the roles they play in the context of their initial communication. They begin a conversation because they sit near each other in class and discuss how much they like or dislike aspects of the course.

The second step in developing friendships is called Friendly Relations. This stage is characterized by communication that moves beyond initial roles as the participants begin to interact with one another to see if there are common interests, as well as an interest to continue getting to know one another. As the students spend more time together and have casual conversations, they may realize a wealth of shared interests. They realize that both were traveling from far distances to go to school and understood each other’s struggle with missing their families. Each of them also loves athletics, especially playing basketball. The development of this friendship occurred as they identified with each other as more than classmates. They saw each other as women of the same age, with similar goals, ambitions, and interests. Moreover, as one of them studied Communication and the other Psychology, they appreciated the differences as well as similarities in their collegiate pursuits.

The third step in developing friendships is called Moving Toward Friendship. In this stage, participants make moves to foster a more personalized friendship. They may begin meeting outside of the setting in which the relationship started, and begin increasing the levels of self-disclosure. Self-disclosure enables the new friends to form bonds of trust. When the students enter this stage, it is right before one joins the basketball club on their college campus. As she starts practices and meetings, she realizes this would be something fun for her and her classmate to do together so she invites her classmate along.

The fourth step in developing friendships is called Nascent Friendship. In this stage, individuals commit to spending more time together. They also may start using the term “friend” to refer to each other as opposed to “a person in my history class” or “this guy I work with”. The interactions extend beyond the initial roles as participants work out their own private communication rules and norms. For example, they may start calling or texting on a regular basis or reserving certain times and activities for each other such as going on evening runs together. As time goes on, the students start texting each other more frequently just to tell each other a funny story that happened during the day, to make plans for going out to eat, or to plan for meeting at the gym to work out.

The fifth step in developing friendships is Stabilized Friendship. In this stage, friends take each other for granted as friends, but not in a negative way. Because the friendship is solid, they assume each other will be in their lives. There is an assumption of continuity. The communication in this stage is also characterized by a sense of trust as levels of self-disclosure increase and each person feels more comfortable revealing parts of him or herself to the other. This stage can continue indefinitely throughout a lifetime. The friends met when they were freshmen in college. After finishing school some years later, they move to separate regions for graduate school. While they are sad to move away from one another, they know the friendship will continue. They continue to be best friends.

The final step in friendship development is Waning Friendship. As you know, friendships do not always have a happy ending. Many friendships come to an end. Friendships may not simply come to an abrupt end. Many times there are stages that show a decline of a friendship, but in Rawlin’s model, the ending of a friendship is summed up by this step. Perhaps the relationship is too difficult to sustain over large geographic distances. Or, sometimes people change and grow in different directions and have little in common with old friends. Sometimes friendship rules are violated to a degree beyond repair. We spoke earlier of trust as a component of friendships. One common rule of trust is that if we tell friends a secret, they are expected to keep it a secret. If that rule is broken, and a friend continually breaks your trust by telling your secrets to others, you are likely to stop thinking of them as your friend.

Friendships across the Life Span

As we transition between life stages such as adolescence, young adulthood, emerging adulthood, middle age, and later life, our friendships change in many ways.[10] Our relationships begin to deepen in adolescence as we negotiate the confusion of puberty. Then, in early adulthood, many people get to explore their identities and diversify their friendship circle. Later, our lives stabilize and we begin to rely more on friendships with a romantic partner and continue to nurture the friendships that have lasted. Let’s now learn more about the characteristics of friendships across the life span.

Adolescence

Adolescence begins with the onset of puberty and lasts through the teen years. We typically make our first voluntary close social relationships during adolescence as cognitive and emotional skills develop. At this time, our friendships are usually with others of the same age/grade in school, gender, and race, and friends typically have similar attitudes about academics and similar values.[11] These early friendships allow us to test our interpersonal skills, which affects the relationships we will have later in life. For example, emotional processing, empathy, self-disclosure, and conflict become features of adolescent friendships in new ways and must be managed.[12]

Adolescents begin to see friends rather than parents as providers of social support, as friends help negotiate the various emotional problems often experienced for the first time.[13]

This new dependence on friendships can also create problems. For example, as adolescents progress through puberty and forward on their identity search, they may experience some jealousy and possessiveness in their friendships as they attempt to balance the tensions between their dependence on and independence from friends. Additionally, as adolescents articulate their identities, they look for acceptance and validation of self in their friends, especially given the increase in self-consciousness experienced by most adolescents.[14] Those who do not form satisfying relationships during this time may miss out on opportunities for developing communication competence, leading to lower performance at work or school and higher rates of depression.[15] The transition to college marks a move from adolescence to early adulthood and opens new opportunities for friendship and challenges in dealing with the separation from hometown friends.

Early Adulthood

Early adulthood encompasses the time from around eighteen to twenty-nine years of age, and although not every person in this age group goes to college, most of the research on early adult friendships focuses on college students. Those who have the opportunity to head to college will likely find a canvas for exploration and experimentation with various life and relational choices relatively free from the emotional, time, and financial constraints of starting their own family that may come later in life.[16]

As we transition from adolescence to early adulthood, we are still formulating our understanding of relational processes, but people report that their friendships are more intimate than the ones they had in adolescence. During this time, friends provide important feedback on self-concept, careers, romantic and/or sexual relationships, and civic, social, political, and extracurricular activities. It is inevitable that young adults will lose some ties to their friends from adolescence during this transition, which has positive and negative consequences. Investment in friendships from adolescence provides a sense of continuity during the often rough transition to college. These friendships may also help set standards for future friendships, meaning the old friendships are a base for comparison for new friends. Obviously this is a beneficial situation relative to the quality of the old friendship. If the old friendship was not a healthy one, using it as the standard for new friendships is a bad idea. Additionally, nurturing older friendships at the expense of meeting new people and experiencing new social situations may impede personal growth during this period.

Adulthood

Adult friendships span a larger period of time than the previous life stages discussed, as adulthood encompasses the period from thirty to sixty-five years old.[17] The exploration that occurs for most middle-class people in early adulthood gives way to less opportunity for friendships in adulthood, as many in this period settle into careers, nourish long-term relationships, and have children of their own. These new aspects of life bring more time constraints and interpersonal and task obligations, and with these obligations comes an increased desire for stability and continuity. Adult friendships tend to occur between people who are similar in terms of career position, race, age, partner status, class, and education level. This is partly due to the narrowed social networks people join as they become more educated and attain higher career positions. Therefore, finding friends through religious affiliation, neighborhood, work, or civic engagement is likely to result in similarity between friends.[18]

Even as social networks narrow, adults are also more likely than young adults to rely on their friends to help them process thoughts and emotions related to their partnerships or other interpersonal relationships.[19] For example, a person may rely on a romantic partner to help process through work relationships and close coworkers to help process through family relationships. Work life and home life become connected in important ways, as career (money making) intersects with and supports the desires for stability (home making).[20] Since home and career are primary focuses, socializing outside of those areas may be limited to interactions with family (parents, siblings, and in-laws) if they are geographically close. In situations where family isn’t close by, adults’ close or best friends may adopt kinship roles, and a child may call a parent’s close friend “Uncle Andy” even if they are not related. Spouses or partners are expected to be friends; it is often expressed that the best partner is one who can also serve as best friend, and having a partner as a best friend can be convenient if time outside the home is limited by parental responsibilities. There is not much research on friendships in late middle age (ages fifty to sixty-five), but it has been noted that relationships with partners may become even more important during this time, as parenting responsibilities diminish with grown children and careers and finances stabilize. Partners who have successfully navigated their middle age may feel a bonding sense of accomplishment with each other and with any close friends with whom they shared these experiences.[21]

Later Life

Friendships in later-life adulthood, which begins in one’s sixties, are often remnants of previous friends and friendship patterns. Those who have typically had a gregarious social life will continue to associate with friends if physically and mentally able, and those who relied primarily on a partner, family, or limited close friends will have more limited, but perhaps equally rewarding, interactions. Friendships that have extended from adulthood or earlier are often “old” or “best” friendships that offer a look into a dyad’s shared past. Given that geographic relocation is common in early adulthood, these friends may be physically distant, but if investment in occasional contact or visits preserved the friendship, these friends are likely able to pick up where they left off.[22] However, biological aging and the social stereotypes and stigma associated with later life and aging begin to affect communication patterns.

Obviously, our physical and mental abilities affect our socializing and activities and vary widely from person to person and age to age. Mobility may be limited due to declining health, and retiring limits the social interactions one had at work and work-related events.[23] People may continue to work and lead physically and socially active lives decades past the marker of later life, which occurs around age sixty-five. Regardless of when these changes begin, it is common and normal for our opportunities to interact with wide friendship circles to diminish as our abilities decline. Early later life may be marked by a transition to partial or full retirement if a person is socioeconomically privileged enough to do so. For some, retirement is a time to settle into a quiet routine in the same geographic place, perhaps becoming even more involved in hobbies and civic organizations, which may increase social interaction and the potential for friendships. Others may move to a more desirable place or climate and go through the process of starting over with new friends. For health or personal reasons, some in later life live in assisted-living facilities. Later-life adults in these facilities may make friends based primarily on proximity, just as many college students in early adulthood do in the similarly age-segregated environment of a residence hall.[24]

Friendships in later life provide emotional support that is often only applicable during this life stage. For example, given the general stigma against aging and illness, friends may be able to shield each other from negative judgments from others and help each other maintain a positive self-concept.[25] Friends can also be instrumental in providing support after the death of a partner. Men, especially, may need this type of support, as men are more likely than women to consider their spouse their sole confidante, which means the death of the wife may end a later-life man’s most important friendship. Women who lose a partner also go through considerable life changes, and in general more women are left single after the death of a spouse than men due to men’s shorter life span and the tendency for men to be a few years older than their wives. Given this fact, it is not surprising that widows in particular may turn to other single women for support. Overall, providing support in later life is important given the likelihood of declining health. In the case of declining health, some may turn to family instead of friends for support to avoid overburdening friends with requests for assistance. However, turning to a friend for support is not completely burdensome, as research shows that feeling needed helps older people maintain a positive well-being.[26]

Gender and Friendship

Gender influences our friendships and has received much attention, as people try to figure out how different men and women’s friendships are. There is a conception that men’s friendships are less intimate than women’s based on the stereotype that men do not express emotions. In fact, men report a similar amount of intimacy in their friendships as women but are less likely than women to explicitly express affection verbally (e.g., saying “I love you”) and nonverbally (e.g., through touching or embracing) toward their same-gender friends.[27]This is not surprising, given the societal taboos against same-gender expressions of affection, especially between men, even though an increasing number of men are more comfortable expressing affection toward other men and women. However, researchers have wondered if men communicate affection in more implicit ways that are still understood by the other friend. Men may use shared activities as a way to express closeness—for example, by doing favors for each other, engaging in friendly competition, joking, sharing resources, or teaching each other new skills.[28] Some scholars have argued that there is a bias toward viewing intimacy as feminine, which may have skewed research on men’s friendships. While verbal expressions of intimacy through self-disclosure have been noted as important features of women’s friendships, activity sharing has been the focus in men’s friendships. This research doesn’t argue that one gender’s friendships are better than the other’s, and it concludes that the differences shown in the research regarding expressions of intimacy are not large enough to impact the actual practice of friendships.[29]

Cross-gender friendships are friendships between a male and a female. These friendships diminish in late childhood and early adolescence as boys and girls segregate into separate groups for many activities and socializing, reemerge as possibilities in late adolescence, and reach a peak potential in the college years of early adulthood. Later, adults with spouses or partners are less likely to have cross-sex friendships than single people.[30] In any case, research studies have identified several positive outcomes of cross-gender friendships. Men and women report that they get a richer understanding of how the other gender thinks and feels.[31] It seems these friendships fulfill interaction needs not as commonly met in same-gender friendships. For example, men reported more than women that they rely on their cross-gender friendships for emotional support.[32] Similarly, women reported that they enjoyed the activity-oriented friendships they had with men.[33]

As discussed earlier regarding friends-with-benefits relationships, sexual attraction presents a challenge in cross-gender heterosexual friendships. Even if the friendship does not include sexual feelings or actions, outsiders may view the relationship as sexual or even encourage the friends to become “more than friends.” Aside from the pressures that come with sexual involvement or tension, the exaggerated perceptions of differences between men and women can hinder cross-gender friendships. However, if it were true that men and women are too different to understand each other or be friends, then how could any long-term partnership such as husband/wife, mother/son, father/daughter, or brother/sister be successful or enjoyable?

Key Takeaways

- Friendships are voluntary interpersonal relationships between two people who are usually equals and who mutually influence one another.

- Friendships develop through phases.

- Friendships change throughout our lives as we transition from adolescence to adulthood to later life.

- Cross-gender friendships may offer perspective into gender relationships that same-gender friendships do not, as both men and women report that they get support or enjoyment from their cross-gender friendships. However, there is a potential for sexual tension that complicates these relationships.

Exercises

- Have you ever been in a situation where you didn’t feel like you could “accept applications” for new friends or were more eager than normal to “accept applications” for new friends? What were the environmental or situational factors that led to this situation?

- Getting integrated: Review the types of friendships (reciprocal, associative, and receptive). Which of these types of friendships do you have more of in academic contexts and why? Answer the same question for professional contexts and personal contexts.

- Of the life stages discussed in this chapter, which one are you currently in? How do your friendships match up with the book’s description of friendships at this stage? From your experience, do friendships change between stages the way the book says they do? Why or why not?

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 11–12. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 2. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 271. ↵

- Adapted from C. Arthur VanLear, Ascan Koerner, and Donna M. Allen, “Relationship Typologies,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 103. ↵

- Justin J. Lehmiller, Laura E. VanderDrift, and Janice R. Kelly, “Sex Differences in Approaching Friends with Benefits Relationships,” Journal of Sex Research 48, no. 2–3 (2011): 276. ↵

- Melissa A. Bisson and Timothy R. Levine, “Negotiating a Friends with Benefits Relationship,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 38 (2009): 67. ↵

- Justin J. Lehmiller, Laura E. VanderDrift, and Janice R. Kelly, “Sex Differences in Approaching Friends with Benefits Relationships,” Journal of Sex Research 48, no. 2–3 (2011): 276. ↵

- .Justin J. Lehmiller, Laura E. VanderDrift, and Janice R. Kelly, “Sex Differences in Approaching Friends with Benefits Relationships,” Journal of Sex Research 48, no. 2–3 (2011): 280. ↵

- http://kell.indstate.edu/public-comm-intro/chapter/6-4-developing-and-maintaining-friendships/ ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992). ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 65. ↵

- W. Andrew Collins and Stephanie D. Madsen, “Personal Relationships in Adolescence and Early Adulthood,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 195. ↵

- W. Andrew Collins and Stephanie D. Madsen, “Personal Relationships in Adolescence and Early Adulthood,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 195. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 59–64. ↵

- W. Andrew Collins and Stephanie D. Madsen, “Personal Relationships in Adolescence and Early Adulthood,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 197. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 103. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 157. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 48–49. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 74–75. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 159. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 186. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 217. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 51–52. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 217–26. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 228–31. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 232–33. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 20. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 69. ↵

- Michael Monsour, “Communication and Gender among Adult Friends,” in The Sage Handbook of Gender and Communication, eds. Bonnie J. Dow and Julia T. Wood (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 63. ↵

- William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 182. ↵

- Panayotis Halatsis and Nicolas Christakis, “The Challenge of Sexual Attraction within Heterosexuals’ Cross-Sex Friendship,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26, no. 6–7 (2009): 920. ↵

- Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 68. ↵

- Panayotis Halatsis and Nicolas Christakis, “The Challenge of Sexual Attraction within Heterosexuals’ Cross-Sex Friendship,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26, no. 6–7 (2009): 920. ↵