Social Impact: Archaeology Isn’t Just About the Past

Note – We are currently beta testing this textbook. If you are a student who has been assigned this reading, we would appreciate any feedback you may have. After finishing the chapter, please go to https://forms.gle/3QDm5QYi4ft4wbnXA to complete a short survey.

Christopher L. Hernandez, Ph.D., Loyola University Chicago

Learning Objectives

- Describe archaeological contributions to knowledge that are relevant for contemporary society

- Identify how the process of archaeological research affects people today

- Compare and contrast the role of archaeology in creating ideas of nationhood in the US versus Latin America

- Assess the role archaeologists have in shaping future US social life

Is archaeology relevant for contemporary society? Many in the U.S., many would probably say no. After all, “haven’t archaeologists found everything already? Discovering King Tut’s tomb was really cool, but why should governments and private groups contribute money that might be better spent elsewhere?” These are just some of the comments about my profession I have heard over the years from friends, acquaintances, and strangers. Unlike countries in many other parts of the world, such as Latin America, archaeology in the U.S. is often seen as superfluous or irrelevant. As a subfield of anthropology, archaeology has gained a public image as the study of exotic others. Although many archaeologists investigate Pre-Columbian, Colonial, and U.S. history, the popular appeal of archaeology tends to lie in the oohs and ahhs of making spectacular finds about foreign and exotic peoples (Schiffer 2017; M. E. Smith et al. 2012). This public profile easily lends the field to critique from people who are unfamiliar with or skeptical of archaeologists. The skeptics include powerful figures, such as members of Congress who can influence the federal distribution of research funds (Mervis 2014; L. Smith 2017). Hence, over the past few decades, many prominent scholars have turned to writing works for popular consumption on how archaeology is important and perhaps even necessary (Fagan & Durrani 2019; Joyce 2016; Sabloff 2008; Schiffer 2017; See also in this textbook the chapters by Hendrick, Anderson, and Casper-Denman).

In this chapter, I examine how the process of archaeological inquiry contributes to and challenges aspects of contemporary U.S. society. To build my claims, I divide this chapter into three parts. The first part is focused on the traditional role of archaeologists in society, which is to provide insights about the past and to illuminate the course of the human experience. Part 2 highlights how the process of creating knowledge has important ramifications for contemporary people. The work of archaeologists is inherently a cultural process with political, economic, and social consequences. I examine how in some cases learning about the past has been oppressive for descendant communities. I also discuss steps that archaeologists are taking to address this downside of their work. Last, to really understand how archaeology is socially relevant, I reflect on U.S. culture and history. I use a comparative perspective to highlight the role of archaeology in the U.S. versus Mexico, and demonstrate how the issue of settler-colonialism contributes to the trivialization of the field. I argue that archaeology in the US has not achieved as much prominence as in Mexico because the field is not tied into the creation of a national identity. Instead, studying the human experience beyond the first European settlers of North America threatens to expose a project of elimination that was foundational to the building of a nation. If you are a visual learner or would like to preview of some of the major themes in this chapter, feel free to visit the following links for a couple of 15-minute videos:

Part 1: Contributions of Archaeological Knowledge to Society

By thinking about stuff, or the material world we live with and leave behind, archaeologists can provide a long-term perspective for understanding the human experience in any part of the world. This unique outlook allows us to ask questions with profound impact for how people go about their lives. (For more on how this long-term perspective was established and why it is important, see Special Topics: Establishing Deep Time, below.) Part of this power lies in the use of science. Archaeologists have long used the scientific principles of geology to understand the human experience (see Appendix A). Other examples of archaeology as a science include radiocarbon dating to determine calendar dates for organic materials, chemistry to geographically pinpoint the sources of raw materials, genetics to understand genealogies, and computer modeling of satellite data to understand human movement (Brown & Brown, 2013; Parcak, 2019; Schiffer, 2017). Building from these and many other breakthroughs in the discipline, Smith and colleagues (2012) highlight that archaeology has greatly progressed as a social science. Researchers have compiled a global database of finds that allow for rigorous examination of a range of questions about the human experience (e.g., Fagan & Durrani 2019; Flannery & Marcus 2012; Kintigh et al. 2014). Common themes of investigation include the development of urbanism, the origins of socially stratified societies, how institutionalized leadership positions developed, and societal resilience.

Special Topics: Establishing Deep Time

One of the biggest shocks to cultures across the globe, especially those in Europe, was the establishment of deep time or what is often referred to as prehistory (Gamble & Kruszynski 2009). This classic tale of archaeological impact involved the application of systematic, scientific methods to refute creationist conceptions of time. An often recognized example of a creationist timeline is James Ussher’s creation date of October 23, 4004 BC. Ussher was an Irish scholar and member of the clergy who carefully examined Biblical texts and other documentary records to calculate his particular date for the origins of existence. In the 1800s, many people in Europe and the U.S. accepted Ussher’s timeline for creation. However, in 1859, two works sparked a major shift in Western European and U.S. thought. In this same year, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, and Joseph Prestwich and John Evans documented the presence of human stone tools in the same geologic layers as extinct mammals.

Darwin’s book established the framework for a theory of evolution through natural selection. His argument for species adapting over time to achieve reproductive success in a given environment has been supported by archaeological finds of extinct animal fossils, which include human ancestors such as Homo erectus, Homo habilis, and members of the Australopithecine family (Schiffer, 2017; Shook et al., 2019). Paving the way for these major discoveries in human evolution, John Evans and Joseph Prestwich made the important step of establishing that people existed prior to events recorded in the Bible.

In an 1896 American Geologist obituary written for Joseph Prestwich, the author notes that “prejudices, which stood in the way of acceptance of the evidence of man’s geologic antiquity, can scarcely be understood at the present time, though less than forty years have passed since those now forgotten controversies.” (W.U., 1896, p. 134) The lack of controversy is a testament to the work of Prestwich, his colleague John Evans, and subsequent archaeologists. Today, few in the U.S. would argue that humans and the Earth are only 6,000 years old. Most would hopefully accept that we once coexisted with the mammoth, saber-toothed tiger, and other extinct Ice Age () creatures. Yet, as the quote above highlights, these ideas were far from conventional in 1859. Although many geologists at the time argued the Earth was more than 5,683 years old and that not all human existence was accounted for in the Bible, they still had to develop a case for an alternative perspective to Ussher and other creationist conceptions of time. Perhaps the key lay the archeological record.

Evans and Prestwich were not the first to claim evidence for the association of human with extinct mammals. Their key contribution is the application of geological science with systematic documentation to provide convincing evidence that countered creationist timelines. They gathered critical data at St. Acheul Amiens in the Somme Valley of France.

Evans and Prestwich traveled to the Somme in the spring of 1859 in the hope of finding artifacts or objects that had been relatively undisturbed since their deposition in the soil (Gamble & Kruszynski, 2009). Through careful analysis of geologic layers (i.e., ), they had to establish that any artifacts associated with extinct mammals were not placed there by more recent human activity (i.e., fraud) or moved across geologic layers due to disturbances in the soil. In April 1859, construction workers in the Somme made a promising find. With a team of scientists and a photographer, Evans and Prestwich traveled to St. Acheul Amiens to document a stone handaxe uncovered deep beneath the surface (See link for images: https://blog.geolsoc.org.uk/2020/04/27/photographs-from-the-drift/). The additional scientists bore witness to the discovery and the photographer provided what was then a relatively innovative documentation technique. In the field, Evans and Prestwich recorded depth measurements and a detailed description of the artifact. They analyzed the soil context that contained the axe and found no disturbances. To support their finds at St Acheul Amiens, Prestwich and Evans excavated a similar set of handaxes in Hoxne, England. During a business trip, Evans noticed handaxes in a collector’s case reminiscent of the one found in St Acheul Amiens (Gamble & Kruszynski, 2009). He traced the of the artifacts in the case back to Hoxne. In England, Evans and Prestwich excavated more handaxes that were in the same soil context as extinct mammals. Together, the Hoxne and St Acheul Amiens finds provided the necessary artifacts and geologic evidence to substantiate that humans had lived in a previous geologic era with now extinct animals. This era of human existence not accounted for in written records, known today as prehistory or deep time, provided a major counterclaim to creationist timelines.

To demonstrate how the findings of archaeologists are relevant for contemporary society, I provide three case studies: (1) human-environment relationships; (2) human diseases in archaeological perspective; and (3) scrutinizing histories. The case studies are just a small sample of how archaeologists’ findings are relevant for contemporary society; for further discussion see the works by Fagan and Durrani (2019), Feder (2017), Little (2016), Sabloff (2008), and Schiffer (2017) (see also Appendix A for a classic example of archaeological contributions to knowledge).

Human-Environment Relationships

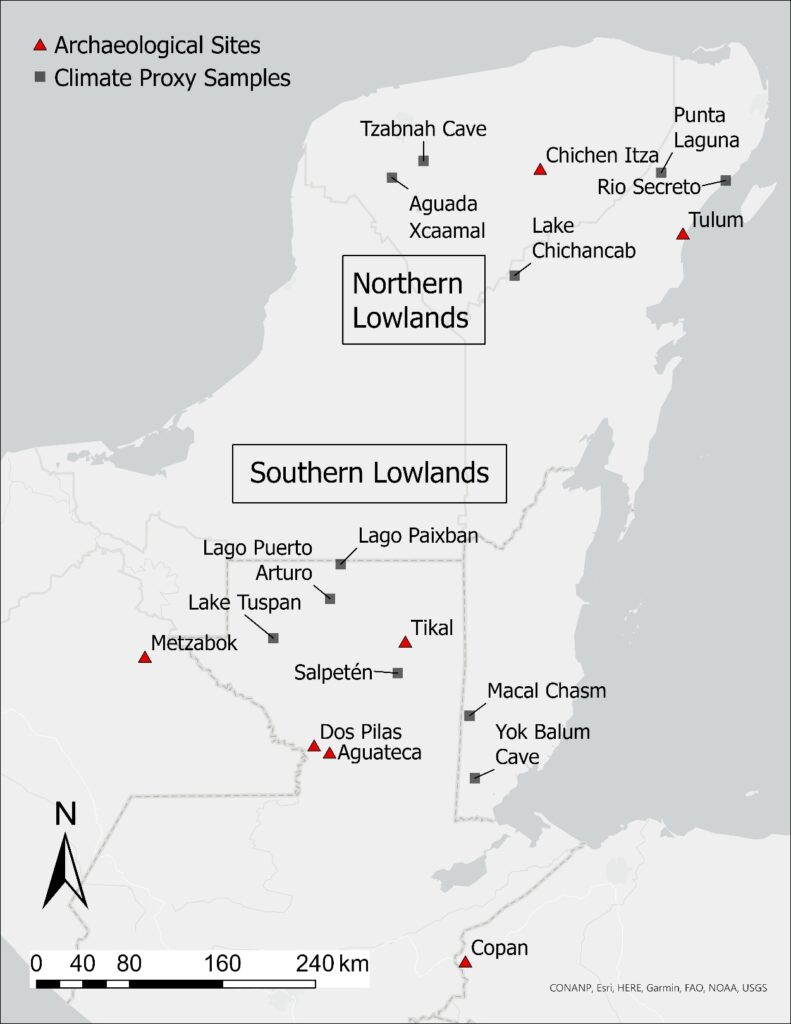

Archaeologists have long thought about human-environment relationships but today they are increasingly concerned with understanding the conditions that led to the growth, decline, and resilience of societies across the globe (Chase & Scarborough 2014; Fagan & Durrani 2019; Kirch 2005; McAnany & Yoffee 2009; Rick & Sandweiss 2020; Tainter 2006). Work in Mesoamerica has demonstrated a series of major droughts coincided with an episode commonly referred to as the Maya “collapse”. I say collapse in quotes because contrary to popular belief, the Maya peoples who created the towering temples and vast jungle cities of the Yucatan peninsula, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador did not disappear (Figures 1 and 2). Millions of Maya descendants continue to live on the land of their ancestors and other parts of the globe, including the United States. Studies of Maya resilience are often tied to researchers observing a pattern in the archaeological record that dates to over a thousand years ago.

When scholars discuss collapse in the Maya area they are often referring to a process that occurred at the end of what is termed the Classic period (CE 200 – 900). The Classic period is when the southern lowland rainforests of the Maya area experienced their peak population levels (Figure 3). Divine rulers administered cities, formed alliances, and fought with rivals. However, around CE 700, the power of Maya rulers and the growth of urban centers in this region of the world began to diminish. The archaeological record, which includes hieroglyphic texts, provides increased evidence of warfare and a general decline in monumental construction (Figure 4). By CE 900, the cities are largely depopulated and over time incorporated back into the rainforest (Figure 1). What happened to the once thriving Mayas?

Sparked in large part by paleo-climatological research conducted in the 1990s (Hodell et al. 1995), archaeologists are increasingly examining the role of drought in the collapse. Much of this research utilizes lake cores and other sources of ancient rainfall data from the northern part of the Maya lowlands (Figure 3). The most refined source of data is a from Yok Balum cave in Belize. Through U-Th (Uranium-Thorium) dating, Kennett et al. (2012) were able to date sequences of stalagmite growth with an accuracy of plus or minus 17 years. In other words, the researchers were able to narrow down the age of the growth sequences to a window of dates spanning roughly 34 years. During the Terminal Classic (CE 700 to 900) or roughly the period of collapse, their plus or minus was closer to five years or less. For archaeologists accustomed to with ranges in decades or centuries, it is remarkable Kennett and colleagues were to able arrive at such a narrow time frame. Via the measurement of oxygen (δ18O) in sequences of stalagmite growth, they were able to estimate annual rainfall. Based on the record of rainfall rates that could be dated with high precision and accuracy, Kennett et al. (2012) argue episodes of multidecadal droughts led to a two-stage collapse. The first episode of multidecadal droughts occurred in the seventh century AD, which was followed by another episode of multiple multidecadal droughts that occurred from CE 820 to 870. Overall, they found evidence of a drying trend that lasted from CE 640 to 1020.

Prolonged droughts would have been destructive for Classic Period lowland Maya communities because the large populations living in densely packed areas were dependent on agricultural production (Hoggarth et al., 2017; Iannone, 2014; Kennett et al., 2012). The surplus generated by farmers allowed for a population boom and the formation of an elite strata that included divine rulers and scribes. Cross-cultural research suggests a lack of agricultural production and resulting societal stress might have contributed to the greater evidence of warfare seen toward the end of the Classic Period (LeBlanc & Register 2003; Sabloff 2008; Zhang et al. 2007). Greater social conflict might have had a cascading effect by leading to the destruction and accelerated abandonment of communities, such as the sites of Dos Pilas and Aguateca in Guatemala. As drought was exerting pressure on agriculture and population levels, Maya communities seem to have increasingly turned to warfare in an attempt to alleviate some of the stress. Others likely migrated out of the southern lowlands in search of a reprieve from the turmoil. Although much of the collapse scenario I outlined in this and previous paragraphs is plausible, further investigation is necessary.

If Maya agricultural output was severely affected by low rainfall, then it is up to researchers to provide the archaeological evidence that demonstrates decreased farming yields coincided with the multidecadal droughts or the extended period of low rainfall, or both. People can have a number of responses to drought, including the development of new agricultural techniques that mitigate the effects of low rainfall and perhaps increase productivity (e.g., Boserup 1965; Kirch & Zimmerer 2011). A better understanding of the conditions that led to the collapse, which includes an analysis of how the Mayas reacted to a shifting climate, will allow archaeologists to utilize their findings to help us think about current conditions. If climate change led to low rainfall that triggered massive depopulation, might our societies be facing similar conditions as the earth’s atmosphere and oceans continue to warm? Or, have we mitigated the major issues faced by the ancient Mayas? More importantly, will we, as a species, respond to global climate change with a resiliency similar to that demonstrated by Maya peoples? If climate change did lead to the collapse, then Maya peoples endured through the turmoil and centuries later confronted the horrors of colonization. Despite the challenges, Maya peoples have found ways to persist and in some cases thrive into the present (e.g., Fischer & Brown 1996; Menchú 1984).

Human Infectious Diseases in Archaeological Perspective

The issue of human resilience is at the forefront of my thoughts because I began writing this chapter during a time government officials projected to be the worst for the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is now a year after I wrote the previous sentence and the pandemic shows no signs of abating. With grim daily disease and mortality numbers, it would be easy to put archaeology aside and focus on other pursuits. Yet, the examination of material remains can contribute important findings for epidemiologists and other health professionals. While biomedical researchers continue their work to find proper treatments for COVID-19 and other illnesses, paleopathologists can provide a deeper understanding of the long-term human experience of infectious diseases.

Invasive, disease causing organisms often affect soft tissue, such as the lungs or intestines, which preserve poorly over time. Consequently, archaeologists have primarily studied illnesses that cause bone modifications (e.g., Buikstra, 1981). Via skeletal analysis, bioarchaeologists and paleopathologists have provided evidence of past infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, brucellosis, and syphilis (Roberts & Manchester, 2010). Perhaps one of the most significant results from this work is the claim that the switch from a mobile, foraging lifestyle (i.e., hunting and gathering) to a sedentary lifestyle based on domesticated plants and animals (i.e., the Neolithic Revolution) resulted in an overall decline in health for human populations (Barrett et al. 1998).

Through the analysis of remains that pertain to the Neolithic Revolution in various parts of the world, researchers have observed increased bone lesions that indicate under nutrition and infectious disease (Barrett et al. 1998; Cohen 1989; Cohen and Armelagos 1984). Presumably, as the growth of human populations accelerated with the switch to a subsistence based primarily on , we became increasingly concentrated into clusters of settlement. The formation of increasingly dense communities and living with domesticated animals provided more opportunity for infectious diseases to spread and thrive. It is important to note that a reliance on bone modification, which is a slow process, means that diseases with rapid mortality are underrepresented in the archaeological record. For example, if future archaeologists excavate the graves of people who succumbed to COVID-19, they probably will not find skeletal modifications caused by the disease. Nevertheless, some of the detection issues can be overcome by utilizing documentary and biomolecular analysis (Brown and Brown 2013).

The Black Death (CE 1347 to 1349) in Europe has received considerable attention from investigators interested in the organism that caused the epidemic and human reactions to the illness (McKinley, 2020). One of the most prominent case studies of the plague is a cemetery uncovered in East Smithfield, England. Documentary records were used to confirm that the Royal Mint cemetery of East Smithfield was an emergency burial ground for people who succumbed to the Black Death (Antoine 2008). At the site, archaeologists have uncovered mass burials with the remains of several hundred plague victims. Researchers have utilized DNA sequences collected from the bones of the interred to examine whether or not the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which causes bubonic plague, was the organism that caused the illness known as the Black Death (Antoine 2008; Bos et al. 2011). This genetic research has generated controversy but ongoing advances in the study of ancient DNA have provided strong evidence that the Black Death was caused by Yersinia pestis. DNA research has also provided data to suggest that this bacteria might have been tied to an earlier epidemic known as the Plague of Justinian that occurred from CE 541 to 543 (Wagner et al., 2014).

Archaeologists may also contribute to the debate surrounding the role of rats in the transmission of the Black Death. Based on her extensive research, Antoine (2008) proposes the following:

“The black rat (Rattus rattus) is regarded by some as the dominant reservoir of Yersinia pestis and this species may have eventually been displaced and succeeded throughout Europe by the bigger brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). As the brown rat is believed to be less likely to transmit the [plague carrying] fleas to humans […] [c]hanges in rodent ecology may thus explain the complex patterns of eruption, disappearance and re-emergence of plague that continued in Europe over many centuries.”

As the quote above underscores, we cannot assume that humans have overcome past illnesses by developing immunity. Instead, the spread and eventual decline of certain diseases may have been caused by environmental changes that occurred through varying degrees of intentional and unintentional human intervention. Thus, as archaeologists continue to develop new methods of detection, we may be able to contribute a long-term understanding of human relationships with infectious organisms and disease transmitters that can help people address and perhaps even prevent future pandemics (e.g., Bos et al., 2011).

Scrutinizing Histories

The goal of many archaeologists is ultimately to learn about the past and enrich our understanding of humanity. One of our major contributions to this project is revealing hidden aspects of the past. This work is important because any account of the human experience will intentionally and unintentionally exclude information or contain biases (Brumfiel 1993; Trouillot 1995). For example, ancient written records, which are one among many sources of history (i.e., oral history, archaeology), tend to contain information about rulers and other members of the elite and that ignore everyday people, who form the vast majority of a society’s population. In patriarchal groups, the actions of women are often underrepresented or missing. Moreover, some rulers can choose to re-write history in a manner that pleases them. Once the biases and omissions of histories are understood, investigators can look to expand, fill -in, or refute narratives about the past. For example, archaeologists have revealed a wealth of evidence for people whose lives were omitted from written records. The silenced voices, among many others, include Indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans (Blakey 2020; Supernant 2020). Thanks in part to archaeological finds, we have gained a deeper understanding of how marginalized groups actively shaped the formation of the United States.

The history of the U.S. is often told as one of expansion by triumphant European settlers. The English landed on the East Coast, at Plymouth and Virginia, and, as part of a colonial project, expanded westward until the country was united “from sea to shining sea”. Yet, the lands being settled were not empty or barren. For thousands of years, Native American ancestors created their own histories and cultures associated with the places that Europeans sought to control.

Hindsight tells us that the European-led colonizers eventually displaced most Native American groups, but this process of removal was not simple, universal, or inevitable. Researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that European successes in the Americas would not have been possible without the assistance of Indigenous groups (Dunbar-Ortiz 2014; Restall & Asselbergs 2007; Silverman 2019). The sharing of knowledge and resources between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag at the “First Thanksgiving” is a familiar, though highly mythologized, example. Examples abound for how Native American groups supported, directed, impeded, and even prevented efforts at domination and exploitation by Europeans. For example, the Anishanaabe peoples, who lived in the Straits of Mackinac region of Michigan,, utilized their strategic position along Great Lakes trading routes to exert pressure on Europeans and rival Native American groups (McDonnell, 2015). The inhabitants of the Mackinac area, specifically the Odawa, created an extensive network of kinship alliances that allowed them to wield tremendous political, economic, and military might. With their extensive power, the Odawa were able to direct and even counter colonial efforts by playing on the fears and aspirations of the French and English. Working with the archaeological evidence and written records, investigators have sought to give voice back to groups, such as the Miami, who resisted U.S. assimilation efforts.

The documentary record of early 19th century Miami is biased toward the perspective of U.S. officials, such as President William Henry Harrison, who gave voice to pro-assimilation Native American leaders. Through careful analysis, Mann (1999) demonstrates how reading between the lines reveals clues into the lives and political views of anti-assimilation Miami. Harrison, then governor of Indiana, was fully aware of rival factions as he stated “…when Wells [a U.S. Indian Agent] speaks of the Miami Nation being of this or that opinion he must be understood as meaning no more than the Turtle [a pro-assimilation Miami leader] and himself.” (Esarey 1922: 76-77) Further clues of the intra-Miami dispute can be found at the Ehler site, which is one of several settlements located at the Maumee-Wabash portage of Indiana (Mann 1999). Several Europeans traveled through and left accounts of the region, including Harrison who burned Native homes and fields as part of his campaign in the War of 1812. However, the Ehler site is not mentioned in any known written history. The omission of the settlement from extant records could be due to bias against spreading the views of anti-assimilation groups and/or intentional effort on the part of this Native community to remain hidden. Excavations at the Ehler site have revealed an abundance of British-made gun flints. The presence of the weapon parts suggest the British were engaging in illicit exchanges with the Miami prior to and in likely preparation for a war with the recently independent U.S. Thus, the omission of the Ehler site from written records may be tied to political efforts on the part of multiple groups to obscure the presence and activities of anti-assimilation Miami. By harnessing the power of material remains and a long-term perspective of the human experience, archaeologists can shape how we think about the past and ourselves.

Part 2: Reflecting on How We Do Archaeology

The impact of archaeology lies in more than results or findings about the past. Although archaeologists have long reflected on the how they do research, more recent work has emphasized how the process of learning about the past affects contemporary people. Doing archaeology has political, economic, and other ramifications that can benefit some and oppress others. Thus, careful consideration is necessary of how the practice of archaeology relates to various

The emphasis on self-reflection in U.S. archaeology grew along with similar trends in cultural anthropology. In the 1980s, cultural anthropologists placed greater attention on examining the societal implications of how they create knowledge and write about other groups of people. Paired with this self-reflection in anthropology, archaeologists also began to place greater emphasis on how the researcher and their social context (i.e., cultural assumptions, politics, and economics) affect interpretation. For example, feminist scholars demonstrated that archaeological interpretations of the past were and often continue to be riddled with gender bias that is tied to wider contemporary cultural assumptions and ideologies (Brumfiel 1993; Conkey and Spector 1984; Moen 2019). Man-the-hunter and woman-the-gatherer models seemingly supported the premise that men provided meat that was the primary source of food for the family. Women, in addition to gathering some plant-based sustenance, supposedly stayed at home to process what the men acquired. The models neatly supported conservative U.S. gender ideals, in which the man provides for the family by going to work and the wife tends the home. However, the claims of past gender roles were based primarily on ethnographic analogy with little support from the archaeological record. Distinguishing gendered activity in the deep human past requires careful analysis because stones rarely contain imprints of the gender that used them and never say “I was used by X gender(s).” Instead, researchers often rely on materials recovered from burials to determine how activities were patterned in the past.

Mortuary analysis, like most other fields of archaeological research, is subject to bias against women and other genders, such as in cases of researchers assuming that skeletal remains buried with weapons were men (Moen 2019). Moreover, it cannot be assumed that sex and gender were equivalent categories in the past or in other cultures. Decades of anthropological and archaeological research has revealed that gender in the past was dynamic, fluid, and varied across cultures (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2020). For example, if skeletal analysis reveals that an individual was male, we cannot assume the person self-identified or was identified by others as a man in their society. With the above issues in mind, it is important to note that over the last few decades the sexing of skeletons, via bioarchaeological and DNA analysis, has revealed that males are not the only sex buried with swords and other weapons. Not all warriors are male! The push by feminists and other scholars for greater self-reflection and engagement with the contemporary power dynamics of doing research opened spaces for archaeologists to challenge existing scientific practices.

Since the 1980s, myriad new approaches to archaeology have arisen with community and collaborative archaeologies perhaps bringing a radically new approach to the field (McAnany & Rowe 2015; Wylie 2015). Growing out of multiple strands of thought that were heavily influenced by Indigenous scholarship and efforts to engage the general public, community and collaborative archaeologists have stressed doing research in partnership with a variety of stakeholders. The stakeholders who have received the greatest attention are those who live near fieldwork sites and/or claim descent from the people who created the record studied by archaeologists.

In the U.S., Native American scholars, such as Vine Deloria Jr. (1988), challenged researchers by demonstrating that archaeological investigation was generally conducted without the consent of descendants, desecrated sacred sites by disturbing the landscape and human remains, and stripped Indigenous peoples of their heritage. The critiques of Native American scholars found reception among anthropologists and archaeologists who were reflecting on how their work perpetuated oppression. For example, Trigger (1984) demonstrates how archaeology has predominantly been practiced as part of imperialist, colonialist, and nationalist projects. The processes discussed by Trigger can be seen throughout the history of Mexican heritage work.

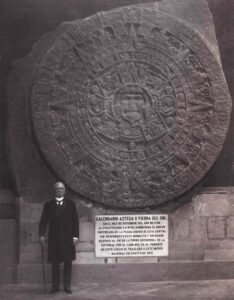

Similar to other Latin American nations, elites (i.e., politicians, intellectuals) in Mexico City during the 1800s made a concerted effort to distance a recently independent Mexico from Spain by promoting a national identity with a claim to Indigenous roots. An important part of this project was the collection and display of Indigenous material remains (Bueno 2016). For example, the consolidation of Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Sun was a centerpiece for Mexico’s 100th anniversary celebration (Figure 5). As part of this nation-building effort, Porfirio Díaz, former long-term President of Mexico, proudly posed next to the Aztec Calendar Stone for a picture intended to display the glory of Mexico’s ancient past and proclaim that the country had established itself as a modern nation because it could protect its own heritage (Figure 6). Yet, this process of nation building generally oppressed Indigenous descendants.

Contemporary Indigenous descendants, such as the Mayas, have often had little say in what the Mexican or other federal governments did with their heritage. Ancient Maya sites, such as Chichen Itza and Tulum, were transformed by foreign investors, politicians, and archaeologists into tourism hot spots (Breglia 2006; Castañeda 1996). As tourist attractions, archaeological sites in Mexico generate billions in income but very little of that money reaches the hands of the Mayas and other descendant communities who generally live in poverty. To address the oppressive nationalist and colonialist legacies of archaeology, recent movements toward collaborative research with descendant communities have begun to fundamentally transform the . The core goal of this reshaping is to develop projects that are conducted with, by, and for Indigenous and descendant groups. I recently participated in one such initiative.

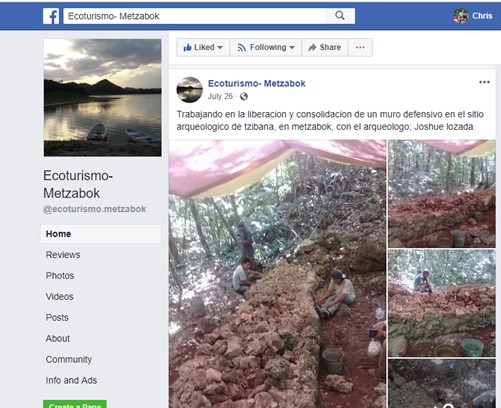

As part of the Mensabak Archaeological Project, I work with the community of Puerto Bello Metzabok in Chiapas, Mexico. The town is home to about 150 Lacandon and Tzeltal Mayas, and is within the wider Naha-Metzabok UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (Figure 7). All archaeological investigation in the biosphere is conducted with the permission of the Puerto Bello Metzabok community government. Locals fulfill various roles on the project, including supervisors, excavators, mappers, and laboratory personnel. Through a collaborative research program, the Mensabak Archaeological Project provides a temporary stream of income and builds local capacity in technical skills and archaeological science, such as digital mapping, sampling methods, stratigraphy, and radiocarbon dating. In the process, we fulfill requests from the people of Metzabok to share our knowledge and financially assist their impoverished community.

Building from our collaborative partnership, in the summer of 2018, I worked with Metzabok community members and a Mexican colleague from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) to consolidate a small ancient fortification (Figure 8). Over the course of several weeks, we systematically excavated and dismantled the remains of a stone wall to understand what it would have looked like in the past. Next, we began the task of reconstructing the fortification to resemble its appearance from over 500 years ago. This process can be strenuous, but we liven the atmosphere through open conservation. Themes of discussion range from the latest gossip to the identification of artifacts. For example, we often debate whether finds of stone fragments are the remains of stone tool production (i.e., flakes). Locals find it hilarious when a fragment I thought was a stone tool turns out to be a naturally broken rock. The final say in these conversations often rests with local elders who in the past engaged in production. Their experience lends them some authority to settle debates but many Metzabok community members are not afraid to challenge authoritative arguments. Overall, via collaborative archaeology that includes open conversation, we prepared a tourist attraction that is managed by and for the benefit of locals.

When archaeologists partner with Indigenous communities to actively confront the legacies of nationalist, colonialist, and imperialist oppression, they are working to promote social justice. We did this in Metzabok by developing an archaeological project that is done with, by, and for an Indigenous descendant community. Our work in Metzabok is just one example of many projects that are striving to address legacies of oppression (e.g., Atalay et al. 2016; Battle-Baptiste 2011; Landau 2019; McAnany 2016; McGuire 2008; Silliman 2008). To their credit, some Latin American governments have implemented initiatives to support Indigenous groups, such as the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI) in Mexico. Yet, the legacies of imperialist, nationalist, and colonialist projects continue to affect Indigenous communities all over the world.

Part 3: Why Is the Issue of Relevance So Prominent in the U.S.?

After reading about the many forms of impact archaeologists have had and are having on contemporary life, you may be wondering “what gives”? Why is archaeology so underappreciated in the U.S.? To address core aspects of this question, I will utilize the classic anthropological technique of comparison. By critically reflecting on U.S. and Mexican cultures, I aim to highlight key differences and deeply ingrained assumptions about the role of archaeology in the U.S.

Above I discussed how, in many Latin American countries, archaeology plays a fundamental role in building a national identity and economies based on tourism. The center of the Mexican flag is inspired by the Aztec symbol for the Pre-Columbian city of Tenochtitlan and the national soccer stadium is called the Estadio Azteca or Aztec Stadium. The country even derives its name from the word “Mexica,” which is the name of the Aztec group that controlled Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) and the Pre-Columbian empire encountered by the Spanish. A symbolic past anchored in archaeological remains is also important for attracting tourists. Foreign and domestic visitors flock to Mexico City to see the remains of the Templo Mayor and the Aztec Calendar Stone. Millions of travelers to archaeological sites, such as Teotihuacan and Chichen Itza, lead to the influx and circulation of billions of pesos in the Mexican economy. In fact, tourism accounted for 8.7% of Mexico’s 2018 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (INEGI 2019). Because Mexico’s tourism economy saw severe declines during the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government has invested the equivalent of billions in U.S. dollars to create Maya Train. The train project is designed to increase access to archaeological sites and other sites of cultural tourism in southern Mexico, and thereby, promote economic development for the nation. The U.S., in contrast, places much less emphasis on archaeological tourism or the Pre-Columbian past.

Although tourism did form 2.9% of the 2018 U.S. GDP, archaeology tends to take a back seat in this aspect of the economy (Franks and Osborne 2019). Sites, such as Chaco Canyon (UNM BBER 2021), Cahokia (Winkler 2021), Plymouth Rock (See Plymouth Massachusetts 2021), and Colonial Williamsburg (Yes Williamsburg, 2021) receive millions of visitors every year, but they pale in comparison to the number of visitors to Disney World (Jordan 2019), Yellowstone National Park (National Park Service 2019), or the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (National Park Service 2020). Although Yellowstone does contain archaeological sites, a quick Google search will reveal that they are generally not the main attraction. The discrepancies in archaeological tourism are due in large part to marketing and national conceptions of the past.

For some reason Native American earthen mounds tend to not have the same ooh and ahh factor as the Pyramids in Egypt or Stonehenge in England. Monks Mound at the Mississippian site of Cahokia, Illinois, is massive on a scale comparable to the Egyptian pyramids and the Roman Colosseum (Kehoe 2002: 250) (Figure 9). Native American effigy mounds are large- scale creative efforts that provide testament to the history of Indigenous peoples who had been creating monumental earthworks for more than 5,000 years (e.g., Milner 2021; Sassaman 2005). But, perhaps in the eyes of many tourists, they are not appealing due to the lack of stone construction. Perhaps earthworks are not grandiose in a manner that fits expectations derived from Old World cultures, such as the Great Wall of China, the Taj Mahal in India, or the gothic cathedrals of Europe. Yet, the issues of monumentality and wow factor only address part of the problem because the stone walls of Pueblo Bonito and other settlements in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, are massive on a scale that would rival many heavily visited Old World archaeological sites, such as Stonehenge or Masada in Israel (Figure 10). Thus, the prevalence of earthen constructions and taste are only a few pieces in our puzzle. Another issue with many archaeological sites in the U.S. is they highlight tragedies and contradictions inherent to the national past.

Though little discussed in school textbooks, the history of the U.S. is defined by with Native Americans posing a crucial problem; they lived on the land craved first by British and later by U.S. settlers. When Old World settlers, primarily Europeans and their descendants, arrived in the Americas they had to take land from Native Americans. A accompanied this process of ssession.

The elimination of Native Americans took many forms, including removal, assimilation (i.e., ), and efforts at outright genocide (Wolfe 1999; Sturm 2017). Removal could entail the physical movement of people, which infamously occurred during the Trail of Tears when thousands of Native Americans died as they were forced to relocate from the Southeastern U.S. to lands west of the Mississippi River. This forced migration was just one of many that resulted from the Indian Removal Act that was signed into federal law in 1830. Elimination also included removing signs of Native American presence on the landscape. Thousands of mounds, which formed the archaeological record of Indigenous peoples, have been removed by settlers to create fields, homes, businesses, and a myriad of other constructions. In other cases, the myth of the Moundbuilders was used to deny Native Americans their history and heritage (Feder 2017). When not explained away as natural phenomena, Monks Mound at Cahokia and other monumental earthworks were argued to be the result of some lost civilization because Native Americans were supposedly too unsophisticated to create such great works (Also see the Intro chapter and Anderson’s Pseudoarchaeology chapter in this text for more information about how pseudoarchaeology is often based in racism and settler colonialism). In addition to being removed, many Native Americans were placed into assimilation programs. The most infamous attempts at assimilation were Indian boarding schools, which were educational institutions designed to remove Native American children from their reservations in order to “kill the Indian, save the man…” (CISDRC 2021) Salvation meant adopting US settler culture. When assimilation and removal were not sufficient, some turned to genocide. General William Tecumseh Sherman, famous for his “march to the sea” during the US Civil War, wrote in an 1866 telegram to Ulysses S. Grant, “[w]e must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women, and children.” (Yimon 1988:422) In settler colonialism, no Native Americans means no original inhabitants to make alternate land claims that might undermine the project of building a nation and its myths.

Dunbar-Ortiz (2014: 12) argues, “[a]ccording to the origin narrative, the United States was born of rebellion against oppression—against empire—and thus is the product of the first anticolonial revolution for national liberation.” This official origin story is then used as a springboard to tell the history of the country as one of “broadening and deepening democracy” to bring world order (ibid.). The U.S. is argued to be exceptional in part because it promotes the progress of humanity by advancing freedom. Often missing in this narrative is the contradiction that as people of European descent occupied land, most sought to eliminate the Indigenous population. Yet, some efforts to integrate Native American culture and history into the official national narrative do exist.

Similar to Latin American stories of nationhood, the most common method of incorporation into the official U.S. national narrative is to treat Indigenous peoples as the first Americans (e.g., Pringle 2012; Struever and Holton 1979). However, these efforts at integration have found a somewhat limited reception. Groups, such as the Anishnaabe, Pueblo, and many others, have fought hard to maintain their sovereignty and cultural identity. Reservations are a testament to the bitter struggles for land and autonomy faced by Indigenous peoples (Treur 2012). Consequently, many Native Americans reject being incorporated into the official USU.S. national narrative because it represents another attempt at assimilation that seeks to undermine their sovereignty.

Overall, the issue of relevance for archaeologists in the U.S. is complex and the result of multiple factors that include nationalism, settler colonialism, economics, and tastes based on Old World cultural preferences. In the United States, the official story of the nation perpetuates a logic of elimination meant to facilitate an invasion and the taking of land from Native Americans. Although many have been forced to relocate to new lands, Indigenous material remains provide an enduring, tangible reminder of this history of dispossession. Thus, archaeological investigation of the land now called the United States can threaten the status quo by shedding new light on what the national project has sought to erase.

Settler colonialism, which requires a logic of elimination, factors into the devaluing of archaeology in the U.S. Native American history and cultures do not form foundational aspects of how the official story of the nation is told. There are no broadly accepted claims of Cahokia or Pueblo Bonito as places of origin for the U.S. Instead, when a Native American past is mentioned in school textbooks and other media, it is typically in subtle hints or short discussions to the peoples who lived on the land before the settlers. The official history of the U.S. begins on the East Coast and spreads westward. Consequently, most of the archaeological record in North America is treated as foreign or exotic. As something that relates to the other, archaeology can be interesting but is not treated as fundamental to promoting the national interest. However, in Latin American countries, such as Mexico, governments tend to devote resources and labor to promoting archaeological finds and heritage. Doing so heightens the national narrative and bolsters the tourism sector of the economy; prior to the pandemic, the latter formed a larger proportion of the GDP for many Latin American countries when compared to the U.S. It remains to be seen how tourism numbers will rebound as the pandemic subsides. In addition to economics and nationalism, towering stone temples in the jungle and mountain cities seem to fit the taste of tourists that are generally molded from Old World preferences. So, does archeology matter? It does. However, claims to relevance in the U.S. face a multi-pronged opposition that requires further analysis. At the top of the list for future discussion are gender, race, religion, class, sexuality, and how other important aspects of identity factor into settler colonialism.

Conclusion

In a three-part scheme, I have sought to establish a case for the contemporary relevance of archaeology. First, I examined how the findings of archaeologists have reshaped how people think about the past and themselves, as well as provide insights that may help us plan for the future. By examining human-environment relationships across cultures and time, we can better evaluate and address the contemporary issue of global climate change. The same applies to studying infectious diseases in long-term perspectives. People learn by critically reflecting on experience. However, epidemics and societal collapse cannot be replicated in real world experiments. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the past via the archaeological record and learn from the experiences of our ancestors to gain insights on how to deal with some of today’s most pressing issues.

Next, I examined how the process of learning about the past can benefit some and oppress others. The practice of archaeology has political, economic, and many other consequences for contemporary people that must be addressed if the field is to remain vital and continue growing. Archaeologists have already taken steps to promote greater inclusion of women and Indigenous peoples. However, more work remains to be done. For example, the #MeToo movement has demonstrated that the archaeological process is far from equitable (Heath-Stout 2020; Voss 2021a, 2021b).

Last, I compared the role of archaeology in Mexico and the U.S. My analysis revealed how nation building, settler colonialism, economics, and taste contribute to the trivialization of the field. The past, in general, is relevant for who we are and what we do today. However, in the U.S., deep interrogations of the past inherently threaten to reveal the logic of elimination that supported the process of settler colonialism. My third-grade teacher once said in class, “there is no history here [i.e., in the Americas], it’s all in Europe.” As you can tell, her statement bothers me to this day, and after years of reflection, I finally have the tools to confidently state there is a long history in the Americas. However, this history is obscured and trivialized in large part due to settler colonialism. Overall, I hope to have thoroughly demonstrated that archaeology isn’t just about the past. The work of archaeologists matters today and for planning a better tomorrow.

Discussion Questions

- Pretend you are talking to a relative about classes you are taking. When they hear you are studying archaeology, they laugh and call it a waste of time. How might you convince your relative that archaeology can contribute knowledge that is relevant for contemporary society?

- Drawing on one or more examples from this chapter, explain how the process of archaeological research may affect people today.

- In this chapter, Hernandez outlines a stark difference in the way that archaeology is viewed in the United States vs. Latin America. What is this difference and what are some possible reasons for it? Can you think of examples of archaeological research from Africa, Asia, Europe, and/or the Pacific Islands? Is the perception more like Latin America or the United States? Why might this be?

- How might archaeology help to shape future social life in the US and in other countries?

About the Author

Christopher Hernandez (Twitter: @profclh) is an anthropological archaeologist whose research focuses on warfare, social conflict, ethics, praxis, and inequality. He is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at Loyola University Chicago. To address questions about the past, Hernandez collaborates in the archaeological process with a diversity of stakeholders, including local and descendant communities in Chiapas, Mexico. In addition to publishing in academic venues, he engages in public facing scholarship, such as podcasting (“Decolonizing Discovery”), Skype-a-scientist, and creating YouTube content.

Christopher Hernandez (Twitter: @profclh) is an anthropological archaeologist whose research focuses on warfare, social conflict, ethics, praxis, and inequality. He is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at Loyola University Chicago. To address questions about the past, Hernandez collaborates in the archaeological process with a diversity of stakeholders, including local and descendant communities in Chiapas, Mexico. In addition to publishing in academic venues, he engages in public facing scholarship, such as podcasting (“Decolonizing Discovery”), Skype-a-scientist, and creating YouTube content.

References

Atalay, S., Clauss, L. R., McGuire, R. H., & Welch, J. R. (Eds.). (2016). Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects. Routledge.

Battle-Baptiste, W. (2011). Black Feminist Archaeology. Routledge.

Blakey, M. L. (2020). “Archaeology Under the Blinding Light of Race.” Current Anthropology, 61(S22), S183-S197.

Boserup, E. (1965). The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure. Aldine Publishing Company.

Breglia, L. (2006). Monumental Ambivalence: The Politics of Heritage. University of Texas Press.

Brown, K.A, & Brown, T.A. (2013). “Biomolecular Archaeology.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 159-174.

Bueno, C. (2016). The Pursuit of Ruins: Archaeology, History, and the Making of Modern Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

Buikstra, J.E. (Ed.). (1981). Prehistoric Tuberculosis in the Americas. Northwestern University Archaeological Program.

Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (CISDRC). (2021, December 27). “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man”: R. H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans“. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/teach/kill-indian-him-and-save-man-r-h-pratt-education-native-americans.

Castañeda, Q. (1996). In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichen Itza. University of Minnesota Press.

Chase, A.F., & Scarborough, V. (2014). “Diversity, Resiliency, and IHOPE‐Maya: Using the Past to Inform the Present.” Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 24(1), 1-10.

Conkey, M. W., & Spector, J. D. (1984). “Archaeology and the Study of Gender.” Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 7, 1-38.

Deloria Jr., V. (1988). Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. University of Oklahoma Press.

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Beacon Press.

Ebert, C. E., Hoggarth, J. A., & Awe, J. J. (2019). “The Climatic Context for the Formation and Decline of Maya Societies in the Belize River Valley.” Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology, 16, 75-89.

Esarey, L. (1922). Governor’s Messages and Letters. Vol 1. Indiana Historical Society Publications

Fagan, B., & Durrani, N. (2019). Bigger than History: Why Archaeology Matters. Thames & Hudson.

Feder, K. (2017). Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries. Oxford University Press.

Fischer, E.F., & Brown, R.M. (Eds.). (1996). Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala. University of Texas Press.

Flannery, K., & Marcus, J. (2012). The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Harvard University Press.

Franks, C. and Osborne, S. (2019). “U.S. Travel and Tourism Satellite Account for 2008-2018.” Survey of Current Business: The Journal of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, 99(11). https://apps.bea.gov/scb/2019/11-november/pdf/1119-travel-tourism-satellite-account.pdf.

Gamble, C., & Kruszynski, R. (2009). “John Evans, Joseph Prestwich and the Stone That Shattered the Time Barrier. Antiquity, 83(320), 461-475.

Heath-Stout, L. E. (2020). “Who Writes About Archaeology? An Intersectional Study of Authorship in Archaeological Journals.” American Antiquity, 85(3), 407-426.

Hodell, D.A., Curtis, J.H., & Brenner, M. (1995). “Possible Role of Climate in the Collapse of Classic Maya Civilization.” Nature, 375(6530), 391-394.

Hoggarth, J.A., Restall, M., Wood, J.W., & Kennett, D.J. (2017). “Drought and its Demographic Effects in the Maya Lowlands.” Current Anthropology, 58(1), 82-113.

Iannone, G. (2014). The Great Maya Droughts in Cultural Context: Case Studies in Resilience and Vulnerability. University Press of colorado.

INEGI. (2019, December 18) Sala de Prensa. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/saladeprensa/noticia.html?id=5451.

Jordan, A. (2019, May 24). “These are the World’s Most-Visited Theme Parks.” USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/news/2019/05/23/disney-world-magic-kingdom-world-most-visited-theme-park/1206310001/.

Joyce, R.A. (2016). The US House of Representatives Really Hates Archaeology. Berkeley Blog. https://blogs.berkeley.edu/2016/02/13/the-us-house-of-representatives-really-hates-archaeology/.

Kennett, D. J., Breitenbach, S. F., Aquino, V. V., Asmerom, Y., Awe, J., Baldini, J. U., … & Haug, G. H. (2012). “Development and Disintegration of Maya Political Systems in Response to Climate Change.” Science, 338(6108), 788-791.

Kintigh, K. W., Altschul, J. H., Beaudry, M. C., Drennan, R. D., Kinzig, A. P., Kohler, T. A., … & Zeder, M. A. (2014). “Grand Challenges for Archaeology.” American antiquity, 79(1), 5-24.

Kirch, P.V., & Zimmerer, K.S. (2011). “Dynamically Coupled Human and Natural Systems: Hawai‘i as a Model System.” In P. V. Kirch (Ed.), Roots of Conflict (pp. 3-30). School for Advanced Research Press.

Kirch, P.V. (2005). “Archaeology and Global Change: The Holocene Record.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30(1), 409-440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.29.102403.140700

Landau, K. (2019). “The Alma College Archaeological Project: Toward a Community-Based Pedagogy.” Journal of Archaeology and Education, 3(4), 1-23.

LeBlanc, S.A., & Register, K.E. (2003). Constant Battles: The Myth of the Peaceful, Noble Savage. St Martin’s Press.

Little, B.J. (2016). Historical Archaeology: Why the Past Matters. Routledge.

McAnany, P.A., & Rowe, S.M. (2015). “Re-visiting the Field: Collaborative Archaeology as Paradigm Shift.” Journal of Field Archaeology, 40(5), 499-507.

McAnany, P.A., & Yoffee, N. (Eds.). (2009). Questioning Collapse: Human Resilience, Ecological Vulnerability, and the Aftermath of Empire. Cambridge University Press.

Menchú, R. (1984). I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala. Verso Books.

Mervis, J. (2014). “Battle Between NSF and House Science Committee Escalates: How Did It Get This Bad?” Science. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2014/10/battle-between-nsf-and-house-science-committee-escalates-how-did-it-get-bad

McAnany, P. A. (2016). Maya Cultural Heritage: How Archaeologists and Indigenous Communities Engage the Past. Rowman & Littlefield.

McDonnell, M. A. (2015). Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America. Hill and Wang.

McGuire, R. H. (2008). Archaeology as Political Action. University of California Press.

McKinley, K. (2020, April 16). Bubonic Plague Inspired Eerily Similar Reactions Among the Rich as Today’s Pandemic. PBS Newshour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/bubonic-plague-inspired-eerily-similar-reactions-among-the-rich-as-todays-pandemic

Milner, G. R. (2021). The Moundbuilders: Ancient Peoples of Eastern North America. Thames & Hudson.

National Park Service. (2019, September 19). Visitation Statistics. National Park Service: Yellowstone. https://www.nps.gov/yell/planyourvisit/visitationstats.htm.

National Park Service. (2020, May 8). Frequently Asked Questions. National Park Service: National Mall and Memorial Parks. https://www.nps.gov/nama/faqs.htm.

Parcak, S. (2019). Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past. Henry Holt and Company.

Pringle, H. (2012, November 1). “The First Americans.” Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-first-americans/.

Rick, T.C., & Sandweiss, D.H. (2020). “Archaeology, Climate, and Global Change in the Age of Humans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(15), 8250-8253.

Roberts, C., & Manchester, K. (2010). The Archaeology of Disease (3rd ed.). The History Press.

Sabloff, J.A. (2008). Archaeology Matters: Action Archaeology in the Modern World. Left Coast Press.

Schiffer, M.B. (2017). Archaeology’s Footprints in the Modern World. University of Utah Press.

See Plymouth Massachusetts. (2021, December 24). Pilgrim Memorial State Park. See Plymouth Massachusetts. https://seeplymouth.com/listing/pilgrim-trail-pilgrim-state-memorial-park/.

Shook, B., Nelson, K., Aguilera, K., & Braff, L. (Eds.). (2019). Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. American Anthropological Association.

Silliman, S. W. (Ed.). (2008). Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. University of Arizona Press.

Smith, L. (2017). “Fund Science for a New Millennium in America: Lamar Smith.” USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2017/02/22/science-foundation-research-taxpayer-funding-lamar-smith-column/98012732/

Smith, M.E., Feinman, G.M., Drennan, R.D., Earle, T., & Morris, I. (2012). “Archaeology as a Social Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(20), 7617-7621.

Struever, S., & Holton, F. A. (1979). Koster: Americans in Search of Their Prehistoric Past. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Sturm, C. (2017). “Reflections on the Anthropology of Sovereignty and Settler Colonialism: Lessons from Native North America.” Cultural Anthropology, 32(3), 340-348.

Supernant, K. (2020). “Grand Challenge No. 1: Truth And Reconciliation; Archaeological Pedagogy, Indigenous Histories, and Reconciliation in Canada.” Journal of Archaeology and Education, 4(3), 2.

Tainter, J.A. (2006). “Archaeology of Overshoot and Collapse.” Annual Review Anthropology, 35, 59-74.

Treuer, D. (2012). Rez Life: An Indian’s Journey Through Reservation Life. Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Trigger, B.G. (1984). “Alternative Archaeologies: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist.” Man, 19(3), 355-370.

Trouillot, M. R. (2015). Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press.

UNM BBER. (2021, December 24). “National Park Visitation Statistics.” University of New Mexico Bureau of Business and Economic Research. https://bber.unm.edu/national-park-visitation-statistics.

Winkeler, L. (2021, December 10). “Outdoors: Illinois Senators Want Historic Cahokia Mounds to Be a National Park.” The Southern Illinoisan. https://thesouthern.com/outdoors/outdoors-illinois-senators-want-historic-cahokia-mounds-to-be-national-park/article_20067565-a192-530c-83e7-3c5890a0273e.html.

W.U. (1896). “Joseph Prestwich: Born March 12, 1812; died June 23 1896.” The American Geologist, XVIII(2), 133-134.

Wylie, A. (2015). “A Plurality of Pluralisms: Collaborative Practice in Archaeology.” In F. Padovani, A. Richardson & J. Y. Tsou (Eds.), Objectivity in Science: New Perspectives from Science and Technology (Vol. 310, pp. 189-210): Springer.

Voss, B. L. (2021a). “Documenting Cultures of Harassment in Archaeology: A Review and Analysis of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Studies.” American Antiquity 86(2), 244-260.

Voss, B. L. (2021b). “Disrupting Cultures of Harassment in Archaeology: Social-Environmental and Trauma-Informed Approaches to Disciplinary Transformation.” American Antiquity 86(3), 447-464.

Yes Williamsburg (2021, December 23). “Local Economy Highlights.” Yes Williamsburg. https://www.yeswilliamsburg.com/160/Local-Economy-Highlights.

Zhang, D.D., Brecke, P., Lee, H.F., He, Y-Q., & Zhang, J. (2007). “Global Climate Change, War, and Population Decline in Recent Human History.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(49), 19214-19219.

The geologic term for the epoch popularly known as the ice age.

An object that was made and used by humans in the past.

Left in the place where it was found.

A form of analysis that originated in geology. The goal of stratigraphic analysis is to understand the layering of soil in order to make temporal and cultural interpretations.

Generally refers to place of origin but in archaeology is typically used to reference the location where an artifact was found (i.e., depositional context).

a rock formation in a cave formed

over time by accumulating calcium deposited that dripped from the cave ceiling

Dating methods based on the radioactive decay of isotopes, such as Carbon-14 or Potassium-40. By knowing the rate of decay for a radioactive element, researchers can determine the age of artifacts, structures, and stratigraphic layers.

Atoms of the same element that contain different numbers of neutrons.

The study of bones.

Refers to plants and animals that have experienced a human-induced transformation in their reproductive and care needs. This transformation can be both physical and genetic.

A person with an interest or concern in something.

a generalized series of steps or tasks an archaeologist takes to successfully develop, conduct, and complete archaeological projects.

Stone tools and the waste material from their creation.

a type of colonialism based on replacing or displacing a usually Indigenous population with a new settler population

the idea that settler colonial regimes aim to destroy Indigenous groups and societies

the taking away of property or land away from a person or a group

the extermination of an ethnic group's cultural identity