Chapter 9 Public Speaking

9.6b Outlines: Principles, purposes and types

Think of your outline as a living document that grows and takes form throughout your speech-making process. When you first draft your general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement, you could create a new document on your computer and plug those in, essentially starting your outline. As you review your research and distill the information down into separate central ideas that support your specific purpose and thesis, type those statements into the document. Once you’ve chosen your organizational pattern and are ready to incorporate supporting material, you can quote and paraphrase your supporting material along with the bibliographic information needed for your verbal citations into the document. By this point, you have a good working outline, and you can easily cut and paste information to move it around and see how it fits into the main points, subpoints, and sub-subpoints. As your outline continues to take shape, you will want to follow established principles of outlining to ensure a quality speech.

Principles of Outlining

There are principles of outlining you can follow to make your outlining process more efficient and effective. Four principles of outlining are consistency, unity, coherence, and emphasis (DuBois, 1929).

Consistency: In terms of consistency, you should follow standard outlining format. In standard outlining format, main points are indicated by capital roman numerals, subpoints are indicated by capital letters, and sub-subpoints are indicated by Arabic numerals. Further divisions are indicated by either lowercase letters or lowercase roman numerals.

Unity: The principle of unity means that each letter or number represents one idea. One concrete way to help reduce the amount of ideas you include per item is to limit each letter or number to one complete sentence. If you find that one subpoint has more than one idea, you can divide it into two subpoints. Limiting each component of your outline to one idea makes it easier to then plug in supporting material and helps ensure that your speech is coherent. In the following example from a speech arguing that downloading music from peer-to-peer sites should be legal, two ideas are presented as part of a main point.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs helps market new music and doesn’t hurt record sales.

The main point could be broken up into two distinct main points that can be more fully supported.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs helps market new music.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs doesn’t hurt record sales.

Coherence: Following the principle of unity should help your outline adhere to the principle of coherence, which states that there should be a logical and natural flow of ideas, with main points, subpoints, and sub-subpoints connecting to each other (Winans, 1917). Shorter phrases and keywords can make up the speaking outline, but you should write complete sentences throughout your formal outline to ensure coherence. The principle of coherence can also be met by making sure that when dividing a main point or subpoint, you include at least two subdivisions. After all, it defies logic that you could divide anything into just one part. Therefore if you have an A, you must have a B, and if you have a 1, you must have a 2. If you can easily think of one subpoint but are having difficulty identifying another one, that subpoint may not be robust enough to stand on its own. Determining which ideas are coordinate with each other and which are subordinate to each other will help divide supporting information into the outline (Winans, 1917).Coordinate points are on the same level of importance in relation to the thesis of the speech or the central idea of a main point. In the following example, the two main points (I, II) are coordinate with each other. The two subpoints (A, B) are also coordinate with each other. Subordinate points provide evidence or support for a main idea or thesis. In the following example, subpoint A and subpoint B are subordinate to main point II. You can look for specific words to help you determine any errors in distinguishing coordinate and subordinate points. Your points/subpoints are likely coordinate when you would connect the two statements using any of the following: and, but, yet ,or, or also. In the example, the word also appears in B, which connects it, as a coordinate point, to A. The points/subpoints are likely subordinate if you would connect them using the following: since, because, in order that, to explain, or to illustrate. In the example, 1 and 2 are subordinate to A because they support that sentence.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs helps market new music.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs doesn’t hurt record sales.

- John Borland, writing for CNET.com in 2004, cited research conducted by professors from Harvard and the University of North Carolina that observed 1.75 million downloads from two file-sharing programs.

- They conclude that the rapid increase in music downloading over the past few years does not significantly contribute to declining record sales.

- Their research even suggests that the practice of downloading music may even have a “slight positive effect on the sales of the top albums.”

- A 2010 Government Accountability Office Report also states that sampling “pirated” goods could lead consumers to buy the “legitimate” goods.

- John Borland, writing for CNET.com in 2004, cited research conducted by professors from Harvard and the University of North Carolina that observed 1.75 million downloads from two file-sharing programs.

Emphasis: The principle of emphasis states that the material included in your outline should be engaging and balanced. As you place supporting material into your outline, choose the information that will have the most impact on your audience. Choose information that is proxemic and relevant, meaning that it can be easily related to the audience’s lives because it matches their interests or ties into current events or the local area. Remember primacy and recency discussed earlier and place the most engaging information first or last in a main point depending on what kind of effect you want to have. Also make sure your information is balanced. The outline serves as a useful visual representation of the proportions of your speech. You can tell by the amount of space a main point, subpoint, or sub-subpoint takes up in relation to other points of the same level whether or not your speech is balanced. If one subpoint is a half a page, but a main point is only a quarter of a page, then you may want to consider making the subpoint a main point. Each part of your speech doesn’t have to be equal. The first or last point may be more substantial than a middle point if you are following primacy or recency, but overall the speech should be relatively balanced.

The Key Word (Alpha Numeric) Outline

A key word outline is a tool that can help with organizing research that has been done, and to identify areas where more research may be needed. Below is an example of a key word outline on soccer. It will be used as the bases for the full-sentence outline that is next.

Specific Purpose Statement: After listening to my speech my audience will understand why soccer isn’t as popular in the United States and describe some of the actions we should take to change our beliefs and attitudes about the game.

I. Soccer new to United States

A. Globally around for thousands of years

-

- FIFA Present states “….”

- Basil Kane states “…”

B. Reasons not popular in USA

-

- Lots of other sport options

- Short attention span

II. Reasons Americans should like soccer

A. Understand the nature of soccer

B. View soccer as entertainment

The Formal Full Sentence Outline

The formal outline is a full-sentence outline that helps you prepare for your speech. It includes the introduction and conclusion, the main content of the body, key supporting materials, citation information written into the sentences in the outline, and a references page for your speech. The formal outline also includes a title, the general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement. It’s important to note that an outline is different from a script. While a script contains everything that will be said, an outline includes the main content. Therefore you shouldn’t include every word you’re going to say on your outline. This allows you more freedom as a speaker to adapt to your audience during your speech. Students sometimes complain about having to outline speeches or papers, but it is a skill that will help you in other contexts. Being able to break a topic down into logical divisions and then connect the information together will help ensure that you can prepare for complicated tasks or that you’re prepared for meetings or interviews. I use outlines regularly to help me organize my thoughts and prepare for upcoming projects.

Sample Full Sentence Outline

The following outline shows the beginning of a full sentence outline using the standards for formatting and content and can serve as an example as you construct your own outline. Check with your instructor to see if he or she has specific requirements for speech outlines that may differ from what is shown here.

Introduction

Attention getter: GOOOOOOOOOOOOAL! GOAL! GOAL! GOOOOOOAL!

Credibility and psychological orientation: If you’ve ever heard this excited yell coming from your television, then you probably already know that my speech today is about soccer. Like many of you, I played soccer on and off as a kid, but I was never really exposed to the culture of the sport. It wasn’t until recently, when I started to watch some of the World Cup games with international students in my dorm, that I realized what I’d been missing out on. Soccer is the most popular sport in the world, but I bet that, like most US Americans, it only comes on your radar every few years during the World Cup or the Olympics. If, however, you lived anywhere else in the world, soccer (or football, as it is more often called) would likely be a much larger part of your life.

Logical orientation/Preview: In order to persuade you that soccer should be more popular in the United States, I’ll explain why soccer isn’t as popular in the United States and describe some of the actions we should take to change our beliefs and attitudes about the game.

Transition: Let us begin with the problem of soccer’s unpopularity in America.

Body

I. Although soccer has a long history as a sport, it hasn’t taken hold in the United States to the extent that it has in other countries.

- Soccer has been around in one form or another for thousands of years.

-

- The president of FIFA, which is the international governing body for soccer, was quoted in David Goldblatt’s 2008 book, The Ball is Round, as saying, “Football is as old as the world…People have always played some form of football, from its very basic form of kicking a ball around to the game it is today.”

- Basil Kane, author of the book Soccer for American Spectators, reiterates this fact when he states, “Nearly every society at one time or another claimed its own form of kicking game.”

- Despite this history, the United States hasn’t caught “soccer fever” for several different reasons.

- Sports fans in the United States already have lots of options when it comes to playing and watching sports.

- Our own “national sports” such as football, basketball, and baseball take up much of our time and attention, which may prevent people from engaging in an additional sport.

- Statistics unmistakably show that soccer viewership is low as indicated by the much-respected Pew Research group, which reported in 2006 that only 4 percent of adult US Americans they surveyed said that soccer was their favorite sport to watch.

- The attitudes and expectations of sports fans in the United States also prevent soccer’s expansion into the national sports consciousness.

- One reason Americans don’t enjoy soccer as much as other sports is due to our shortened attention span, which has been created by the increasingly fast pace of our more revered sports like football and basketball.

- Our lack of attention span isn’t the only obstacle that limits our appreciation for soccer; we are also set in our expectations.

- Sports fans in the United States already have lots of options when it comes to playing and watching sports.

Transition: Although soccer has many problems that it would need to overcome to be more popular in the United States, I think there are actions we can take now to change our beliefs and attitudes about soccer in order to give it a better chance.

II. Soccer is the most popular sport in the world, and there have to be some good reasons that account for this status.

- As US Americans, we can start to enjoy soccer more if we better understand why the rest of the world loves it so much.

-

- As was mentioned earlier, Chad Nielsen of ESPN.com notes that American sports fans can’t have the same stats obsession with soccer that they do with baseball or football, but fans all over the world obsess about their favorite teams and players.

- Fans argue every day, in bars and cafés from Baghdad to Bogotá, about statistics for goals and assists, but as Nielsen points out, with the game of soccer, such stats still fail to account for varieties of style and competition.

- So even though the statistics may be different, bonding over or arguing about a favorite team or player creates communities of fans that are just as involved and invested as even the most loyal team fans in the United States.

- Additionally, Americans can start to realize that some of the things we might initially find off putting about the sport of soccer are actually some of its strengths.

- The fact that soccer statistics aren’t poured over and used to make predictions makes the game more interesting.

- The fact that the segments of play in soccer are longer and the scoring lower allows for the game to have a longer arc, meaning that anticipation can build and that a game might be won or lost by only one goal after a long and even-matched game.

- We can also begin to enjoy soccer more if we view it as an additional form of entertainment.

- As Americans who like to be entertained, we can seek out soccer games in many different places.

- There is most likely a minor or even a major league soccer stadium team within driving distance of where you live.

- You can also go to soccer games at your local high school, college, or university.

- We can also join the rest of the world in following some of the major soccer celebrities—David Beckham is just the tip of the iceberg.

- As Americans who like to be entertained, we can seek out soccer games in many different places.

- Getting involved in soccer can also help make our society more fit and healthy.

- Soccer can easily be the most athletic sport available to Americans.

- In just one game, the popular soccer player Gennaro Gattuso was calculated to have run about 6.2 miles, says Carl Bialik, a numbers expert who writes for The Wall Street Journal.

- With the growing trend of obesity in America, getting involved in soccer promotes more running and athletic ability than baseball, for instance, could ever provide.

- A press release on FIFA’s official website notes that one hour of soccer three times a week has been shown in research to provide significant physical benefits.

- If that’s not convincing enough, the website ScienceDaily.com reports that the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports published a whole special issue titled Football for Health that contained fourteen articles supporting the health benefits of soccer.

- Last, soccer has been praised for its ability to transcend language, culture, class, and country.

- The nongovernmental organization Soccer for Peace seeks to use the worldwide popularity of soccer as a peacemaking strategy to bridge the divides of race, religion, and socioeconomic class.

- According to their official website, the organization just celebrated its ten-year anniversary in 2012.

- Over those ten years the organization has focused on using soccer to bring together people of different religious faiths, particularly people who are Jewish and Muslim.

- In 2012, three first-year college students, one Christian, one Jew, and one Muslim, dribbled soccer balls for 450 miles across the state of North Carolina to help raise money for Soccer for Peace.

- A press release on the World Association of Nongovernmental Organizations’s official website states that from the dusty refugee camps of Lebanon to the upscale new neighborhoods in Buenos Aires, “soccer turns heads, stops conversations, causes breath to catch, and stirs hearts like virtually no other activity.”

- As was mentioned earlier, Chad Nielsen of ESPN.com notes that American sports fans can’t have the same stats obsession with soccer that they do with baseball or football, but fans all over the world obsess about their favorite teams and players.

Conclusion

Transition to conclusion and summary of importance: In conclusion, soccer is a sport that has a long history, can help you get healthy, and can bring people together.

Logical & Psychological closure: Now that you know some of the obstacles that prevent soccer from becoming more popular in the United States and several actions we can take to change our beliefs and attitudes about soccer, I hope you agree with me that it’s time for the United States to join the rest of the world in welcoming soccer into our society.

Closing statement: The article from BleacherReport.com that I cited earlier closes with the following words that I would like you to take as you leave here today: “We need to learn that just because there is no scoring chance that doesn’t mean it is boring. We need to see that soccer is not for a select few, but for all. We only need two feet and a ball. We need to stand up and appreciate the beautiful game.”

Speaker Notes

Using note cards for your speaking outline will help you be able to move around and gesture more freely than using full sheets of paper.

Justin See (coming back) – My Pile of Index Card – CC BY 2.0.

You may convert your formal outline into a speaking outline on paper or note cards. Note cards are a good option when you want to have more freedom to gesture or know you won’t have a lectern on which to place notes printed on full sheets of paper. In either case, this entails converting the full-sentence outline to a keyword or key-phrase outline. Speakers will need to find a balance between having too much or too little content on their speaking outlines. You want to have enough information to prevent fluency hiccups as you stop to mentally retrieve information, but you don’t want to have so much information that you read your speech, which lessens your eye contact and engagement with the audience. Budgeting sufficient time to work on your speaking outline will allow you to practice your speech with different amounts of notes to find what works best for you. Since the introduction and conclusion are so important, it may be useful to include notes to ensure that you remember to accomplish all the objectives of each.

Aside from including important content on your speaking outline, you may want to include speaking cues. Speaking cues are reminders designed to help your delivery. You may write “(PAUSE)” before and after your preview statement to help you remember that important nonverbal signpost. You might also write “(MAKE EYE CONTACT)” as a reminder not to read unnecessarily from your cards. Overall, my advice is to make your speaking outline work for you. It’s your last line of defense when you’re in front of an audience, so you want it to help you, not hurt you.

Tips for Note Cards

- The 4 × 6 inch index cards provide more space and are easier to hold and move than 3.5 × 5 inch cards.

- Find a balance between having so much information on your cards that you are tempted to read from them and so little information that you have fluency hiccups and verbal fillers while trying to remember what to say.

- Use bullet points on the left-hand side rather than writing in paragraph form, so your eye can easily catch where you need to pick back up after you’ve made eye contact with the audience. Skipping a line between bullet points may also help.

- Include all parts of the introduction/conclusion and signposts for backup.

- Include key supporting material and wording for verbal citations.

- Only write on the front of your cards.

- Do not have a sentence that carries over from one card to the next (can lead to fluency hiccups).

- If you have difficult-to-read handwriting, you may type your speech and tape or glue it to your cards. Use a font that’s large enough for you to see and be neat with the glue or tape so your cards don’t get stuck together.

- Include cues that will help with your delivery. Highlight transitions, verbal citations, or other important information. Include reminders to pause, slow down, breathe, or make eye contact.

- Your cards should be an extension of your body, not something to play with. Don’t wiggle, wring, flip through, or slap your note cards.

- Number your note cards; if they fall you want to be able to quickly reorganize them.

Citing Sources

Citing is important because it enables others to see where you found information cited within a speech, article, or book. Furthermore, not citing information properly is considered plagiarism, so ethically we want to make sure that we give credit to the authors we use in a speech. While there are numerous citation styles to choose from, the two most common style choices for public speaking are APA and MLA.

APA versus MLA Source Citations

Stylerefers to those components or features of a literary composition or oral presentation that have to do with the form of expression rather than the content expressed (e.g., language, punctuation, parenthetical citations, and endnotes). The APA and the MLA have created the two most commonly used style guides in academia today. Generally speaking, scholars in the various social science fields (e.g., psychology, human communication, business) are more likely to useAPA style, and scholars in the various humanities fields (e.g., English, philosophy, rhetoric) are more likely to useMLA style. The two styles are quite different from each other, so learning them does take time. For the purposes of this class, we will use APA style.

As of October 2019, the American Psychological Association published the seventh edition of thePublication Manual of the American Psychological Association(http://www.apastyle.org). The seventh edition provides considerable guidance on working with and citing Internet sources.

APA citation basics[1]

When using APA format, follow the author-date method of in-text citation. This means that the author’s last name and the year of publication for the source should appear in the text, like, for example, (Jones, 1998). One complete reference for each source should appear in the reference list at the end of the paper.

If you are referring to an idea from another work but NOT directly quoting the material, or making reference to an entire book, article or other work, you only have to make reference to the author and year of publication and not the page number in your in-text reference.

On the other hand, if you are directly quoting or borrowing from another work, you should include the page number at the end of the parenthetical citation. Use the abbreviation “p.” (for one page) or “pp.” (for multiple pages) before listing the page number(s). Use an en dash for page ranges. For example, you might write (Jones, 1998, p. 199) or (Jones, 1998, pp. 199–201). This information is reiterated below.

Regardless of how they are referenced, all sources that are cited in the text must appear in the reference list at the end of the paper.

In-text citation capitalization, quotes, and italics/underlining

- Always capitalize proper nouns, including author names and initials: D. Jones.

- If you refer to the title of a source within your paper, capitalize all words that are four letters long or greater within the title of a source: Permanence and Change. Exceptions apply to short words that are verbs, nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and adverbs: Writing New Media, There Is Nothing Left to Lose.

(Note: in your References list, only the first word of a title will be capitalized: Writing new media.)

- When capitalizing titles, capitalize both words in a hyphenated compound word: Natural-Born Cyborgs.

- Capitalize the first word after a dash or colon: “Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo.”

- If the title of the work is italicized in your reference list, italicize it and use title case capitalization in the text: The Closing of the American Mind; The Wizard of Oz; Friends.

- If the title of the work is not italicized in your reference list, use double quotation marks and title case capitalization (even though the reference list uses sentence case): “Multimedia Narration: Constructing Possible Worlds;” “The One Where Chandler Can’t Cry.”

Short quotations

If you are directly quoting from a work, you will need to include the author, year of publication, and page number for the reference (preceded by “p.” for a single page and “pp.” for a span of multiple pages, with the page numbers separated by an en dash).

You can introduce the quotation with a signal phrase that includes the author’s last name followed by the date of publication in parentheses.

If you do not include the author’s name in the text of the sentence, place the author’s last name, the year of publication, and the page number in parentheses after the quotation.

Long quotations

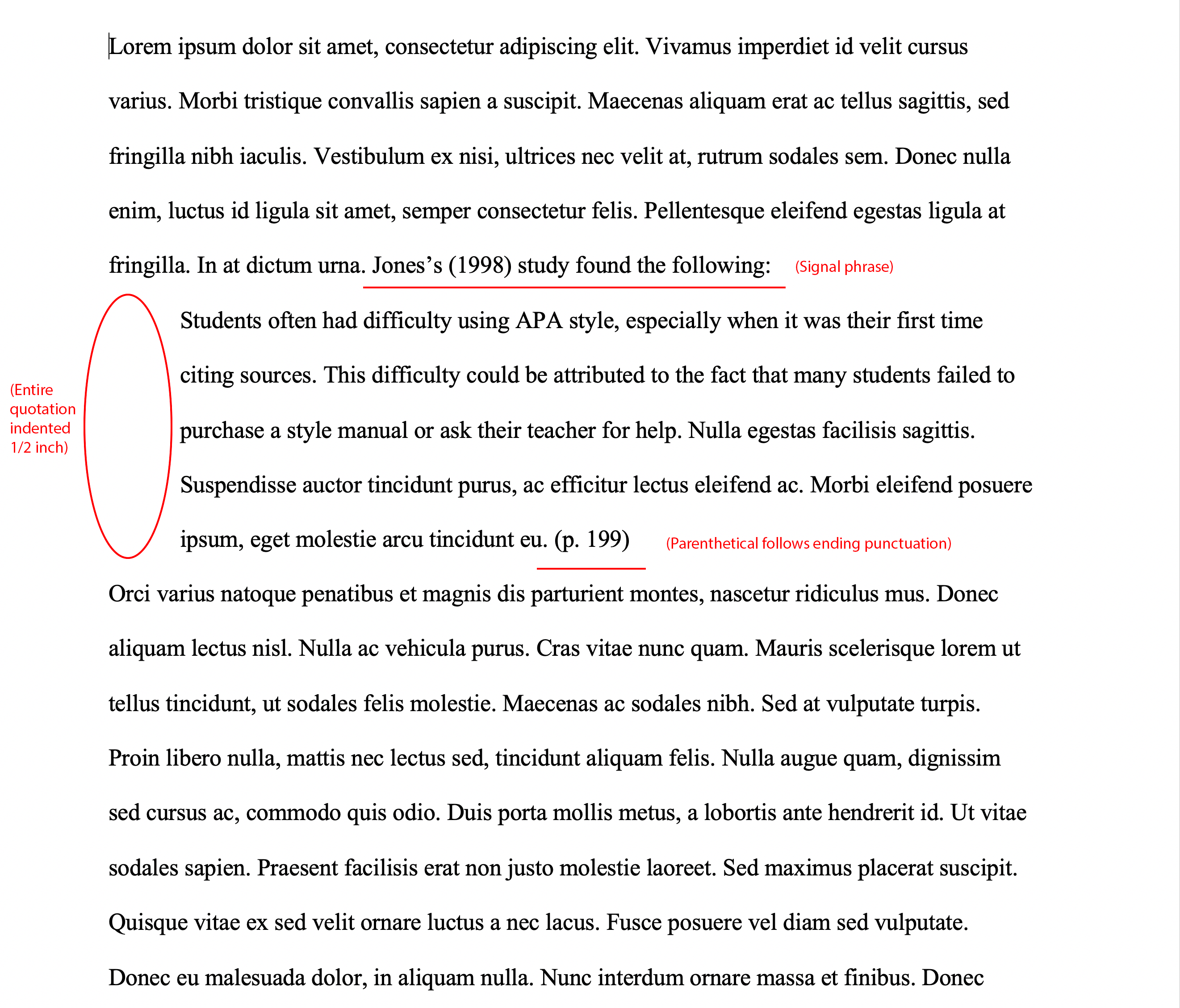

Place direct quotations that are 40 words or longer in a free-standing block of typewritten lines and omit quotation marks. Start the quotation on a new line, indented 1/2 inch from the left margin, i.e., in the same place you would begin a new paragraph. Type the entire quotation on the new margin, and indent the first line of any subsequent paragraph within the quotation 1/2 inch from the new margin. Maintain double-spacing throughout, but do not add an extra blank line before or after it. The parenthetical citation should come after the closing punctuation mark.

Because block quotation formatting is difficult for us to replicate in the OWL’s content management system, we have simply provided a screenshot of a generic example below.

Formatting example for block quotations in APA 7 style.

Quotations from sources without pages

Direct quotations from sources that do not contain pages should not reference a page number. Instead, you may reference another logical identifying element: a paragraph, a chapter number, a section number, a table number, or something else. Older works (like religious texts) can also incorporate special location identifiers like verse numbers. In short: pick a substitute for page numbers that makes sense for your source.

Summary or paraphrase

If you are paraphrasing an idea from another work, you only have to make reference to the author and year of publication in your in-text reference and may omit the page numbers. APA guidelines, however, do encourage including a page range for a summary or paraphrase when it will help the reader find the information in a longer work.

Formatting a Reference List

Your reference list should appear at the end of your paper. It provides the information necessary for a reader to locate and retrieve any source you cite in the body of the paper. Each source you cite in the paper must appear in your reference list; likewise, each entry in the reference list must be cited in your text.

Your references should begin on a new page separate from the text of the essay; label this page “References” in bold, centered at the top of the page (do NOT underline or use quotation marks for the title). All text should be double-spaced just like the rest of your essay.

Basic Rules for Most Sources

- All lines after the first line of each entry in your reference list should be indented one-half inch from the left margin. This is called hanging indentation.

- All authors’ names should be inverted (i.e., last names should be provided first).

- Authors’ first and middle names should be written as initials.

- For example, the reference entry for a source written by Jane Marie Smith would begin with “Smith, J. M.”

- If a middle name isn’t available, just initialize the author’s first name: “Smith, J.”

- Give the last name and first/middle initials for all authors of a particular work up to and including 20 authors (this is a new rule, as APA 6 only required the first six authors). Separate each author’s initials from the next author in the list with a comma. Use an ampersand (&) before the last author’s name. If there are 21 or more authors, use an ellipsis (but no ampersand) after the 19th author, and then add the final author’s name.

- Reference list entries should be alphabetized by the last name of the first author of each work.

- For multiple articles by the same author, or authors listed in the same order, list the entries in chronological order, from earliest to most recent.

- When referring to the titles of books, chapters, articles, reports, webpages, or other sources, capitalize only the first letter of the first word of the title and subtitle, the first word after a colon or a dash in the title, and proper nouns.

- Note again that the titles of academic journals are subject to special rules. See section below.

- Italicize titles of longer works (e.g., books, edited collections, names of newspapers, and so on).

- Do not italicize, underline, or put quotes around the titles of shorter works such as chapters in books or essays in edited collections.

Basic Rules for Articles in Academic Journals

- Present journal titles in full.

- Italicize journal titles.

- Maintain any nonstandard punctuation and capitalization that is used by the journal in its title.

- For example, you should use PhiloSOPHIA instead of Philosophia, or Past & Present instead of Past and Present.

- Capitalize all major words in the titles of journals. Note that this differs from the rule for titling other common sources (like books, reports, webpages, and so on) described above.

- This distinction is based on the type of source being cited. Academic journal titles have all major words capitalized, while other sources’ titles do not.

- Capitalize the first word of the titles and subtitles of journal articles, as well as the first word after a colon or a dash in the title, and any proper nouns.

- Do not italicize or underline the article title.

- Do not enclose the article title in quotes.

- So, for example, if you need to cite an article titled “Deep Blue: The Mysteries of the Marianas Trench” that was published in the journal Oceanographic Study: A Peer-Reviewed Publication, you would write the article title as follows:

- Deep blue: The mysteries of the Marianas Trench.

- …but you would write the journal title as follows:

- Oceanographic Study: A Peer-Reviewed Publication

- So, for example, if you need to cite an article titled “Deep Blue: The Mysteries of the Marianas Trench” that was published in the journal Oceanographic Study: A Peer-Reviewed Publication, you would write the article title as follows:

Table 7.4 “APA Sixth Edition Citations”provides a list of common citation examples that you may need for your speech.

| Research Article in a Journal—One Author | Harmon, M. D. (2006). Affluenza: A world values test.The International Communication Gazette, 68, 119–130. doi: 10.1177/1748048506062228 |

| Research Article in a Journal—Two to Five Authors | Hoffner, C., & Levine, K. J. (2005). Enjoyment of mediated fright and violence: A meta-analysis.Media Psychology, 7, 207–237. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0702_5 |

| Book | Eysenck, H. J. (1982).Personality, genetics, and behavior: Selected papers.New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. |

| Book with 6 or More Authors | Huston, A. C., Donnerstein, E., Fairchild, H., Feshbach, N. D., Katz, P. A., Murray, J. P.,…Zuckerman, D. (1992).Big world, small screen: The role of television in American society. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. |

| Chapter in an Edited Book | Tamobrini, R. (1991). Responding to horror: Determinants of exposure and appeal. In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (Eds.),Responding to the screen: Reception and reaction processes(pp. 305–329). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. |

| Newspaper Article | Thomason, D. (2010, March 31). Dry weather leads to burn ban.The Sentinel Record, p. A1. |

| Magazine Article | Finney, J. (2010, March–April). The new “new deal”: How to communicate a changed employee value proposition to a skeptical audience—and realign employees within the organization.Communication World, 27(2), 27–30. |

| Preprint Version of an Article | Laudel, G., & Gläser, J. (in press). Tensions between evaluations and communication practices.Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management.Retrieved fromhttp://www.laudel.info/pdf/Journal%20articles/06%20Tensions.pdf |

| Blog | Wrench, J. S. (2009, June 3). AMA’s managerial competency model [Web log post]. Retrieved fromhttp://workplacelearning.info/blog/?p=182 |

| Wikipedia | Organizational Communication. (2009, July 11). [Wiki entry]. Retrieved fromhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organizational_communication |

| Vlog | Wrench, J. S. (2009, May 15). Instructional communication [Video file]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.learningjournal.com/Learning-Journal-Videos/instructional-communication.htm |

| Discussion Board | Wrench, J. S. (2009, May 21). NCA’s i-tunes project [Online forum comment]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.linkedin.com/groupAnswers?viewQuestionAndAnswers |

| E-mail List | McAllister, M. (2009, June 19). New listserv: Critical approaches to ads/consumer culture & media studies [Electronic mailing list message]. Retrieved fromhttp://lists.psu.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0906&L=CRTNET&T=0&F=&S=&P=20514 |

| Podcast | Wrench, J. S. (Producer). (2009, July 9).Workplace bullying[Audio podcast]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.communicast.info |

| Electronic-Only Book | Richmond, V. P., Wrench, J. S., & Gorham, J. (2009).Communication, affect, and learning in the classroom(3rd ed.). Retrieved fromhttp://www.jasonswrench.com/affect |

| Electronic-Only Journal Article | Molyneaux, H., O’Donnell, S., Gibson, K., & Singer, J. (2008). Exploring the gender divide on YouTube: An analysis of the creation and reception of vlogs.American Communication Journal, 10(1). Retrieved fromhttp://www.acjournal.org |

| Electronic Version of a Printed Book | Wood, A. F., & Smith, M. J. (2004).Online communication: Linking technology, identity & culture(2nd ed.). Retrieved fromhttp://books.google.com/books |

| Online Magazine | Levine, T. (2009, June). To catch a liar.Communication Currents, 4(3). Retrieved fromhttp://www.communicationcurrents.com |

| Online Newspaper | Clifford, S. (2009, June 1). Online, “a reason to keep going.”The New York Times. Retrieved fromhttp://www.nytimes.com |

| Entry in an Online Reference Work | Viswanth, K. (2008). Health communication. In W. Donsbach (Ed.),The international encyclopedia of communication. Retrieved fromhttp://www.communicationencyclopedia.com. doi: 10.1111/b.9781405131995.2008.x |

| Entry in an Online Reference Work, No Author | Communication. (n.d.). InRandom House dictionary(9th ed.). Retrieved fromhttp://dictionary.reference.com/browse/communication |

| E-Reader Device | Lutgen-Sandvik, P., & Davenport Sypher, B. (2009).Destructive organizational communication: Processes, consequences, & constructive ways of organizing. [Kindle version]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.amazon.com |

Key Takeaways

- The formal outline is a full-sentence outline that helps you prepare for your speech and includes the introduction and conclusion, the main content of the body, citation information written into the sentences of the outline, and a references page.

- The principles of outlining include consistency, unity, coherence, and emphasis.

- Coordinate points in an outline are on the same level of importance in relation to the thesis of the speech or the central idea of a main point. Subordinate points provide evidence for a main idea or thesis.

- The speaking outline is a keyword and phrase outline that helps you deliver your speech and can include speaking cues like “pause,” “make eye contact,” and so on.

Exercises

- What are some practical uses for outlining outside of this class? Which of the principles of outlining do you think would be most important in the workplace and why?

- Identify which pieces of information you may use in your speech are coordinate with each other and subordinate.

- https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html ↵