Chapter 8 Organizational Communication

8.2 Channels & Networks

Organizational communication is held to a higher standard than everyday communication. The consequences of misunderstandings are usually higher and the chances to recognize and correct a mistake are lower. Barriers to communication and skills for improving communication are the same regardless of where the conversation takes place or with whom. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author of best-selling books such as Flow, has noted, “In large organizations the dilution of information as it passes up and down the hierarchy, and horizontally across departments, can undermine the effort to focus on common goals.” Organizations and individuals within organizations need to keep this in mind when going about their job related duties.

Communication Networks

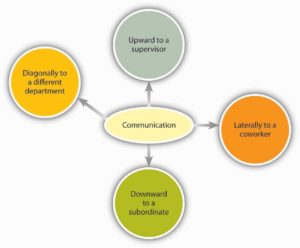

Communication networks refer to the directionality of the communication flow. Communication can flow in a variety of directions within the organization (internal communication) and can flow between the organization and it’s constituents (external communication).

I. Internal Communication Networks

Internal information can flow in four directions in an organization: downward, upward, horizontally, and diagonally. The size, nature, and structure of the organization dictate which direction most of the information flows. In more established and traditional organizations, much of the communication flows in a vertical—downward and upward—direction. In informal firms, such as tech start-ups, information tends to flow horizontally and diagonally. This, of course, is a function of the almost flat organizational hierarchy and the need for collaboration. Unofficial communications, such as those carried in the company grapevine, appear in both types of organizations.

Downward Communication

Downward communication is when company leaders and managers share information with lower-level employees. Unless requested as part of the message, the senders don’t usually expect (or particularly want) to get a response. An example may be an announcement of a new CEO or notice of a merger with a former competitor. Other forms of high-level downward communications include speeches, blogs, podcasts, and videos. The most common types of downward communication are everyday directives of department managers or line managers to employees. These can even be in the form of instruction manuals or company handbooks.

Downward communication delivers information that helps to update the workforce about key organizational changes, new goals, or strategies; provide performance feedback at the organizational level; coordinate initiatives; present an official policy (public relations); or improve worker morale or consumer relations.

Upward Communication

Information moving from lower-level employees to high-level employees is upward communication. For example, upward communication occurs when workers report to a supervisor or when team leaders report to a department manager. Items typically communicated upward include progress reports, proposals for projects, budget estimates, grievances and complaints, suggestions for improvements, and schedule concerns. Sometimes a downward communication prompts an upward response, such as when a manager asks for a recommendation for a replacement part or an estimate of when a project will be completed.

An important goal of many managers today is to encourage spontaneous or voluntary upward communication from employees without the need to ask first. Some companies go so far as to organize contests and provide prizes for the most innovative and creative solutions and suggestions. Before employees feel comfortable making these kinds of suggestions, however, they must trust that management will recognize their contributions and not unintentionally undermine or ignore their efforts. Some organizations have even installed “whistleblower” hotlines that will let employees report dangerous, unethical, or illegal activities anonymously to avoid possible retaliation by higher-ups in the company.

Horizontal and Diagonal Communication Networks

Horizontal communication involves the exchange of information across departments at the same level in an organization (i.e., peer-to-peer communication). The purpose of most horizontal communication is to request support or coordinate activities. People at the same level in the organization can work together to work on problems or issues in an informal and as-needed basis. The manager of the production department can work with the purchasing manager to accelerate or delay the shipment of materials. The finance manager and inventory managers can be looped in so that the organization can achieve the maximum benefit from the coordination. Communications between two employees who report to the same manager is also an example of horizontal communication. Some problems with horizontal communication can arise if one manager is unwilling or unmotivated to share information, or sees efforts to work communally as threatening his position (territorial behavior). In a case like that, the manager at the next level up will need to communicate downward to reinforce the company’s values of cooperation.

Diagonal communication is cross-functional communication between employees at different levels of the organization. For example, if the vice president of sales sends an e-mail to the vice president of manufacturing asking when a product will be available for shipping, this is an example of horizontal communication. But if a sales representative e-mails the vice president of marketing, then diagonal communication has occurred. Whenever communication goes from one department to another department, the sender’s manager should be made part of the loop. A manager may be put in an embarrassing position and appear incompetent if he isn’t aware of everything happening in his department. Trust may be lost and careers damaged by not paying attention to key communication protocols. Diagonal communication is becoming more common in organizations with a flattened, matrix, or product-based structure. Advantages include:

- Building relationships between senior and lower-level employees from different parts of the organization.

- Encouraging an informal flow of information in the organization.

- Reducing the chance of a message being distorted by going through additional filters.

- Reducing the workloads of senior-level managers.

II. External Communication Networks

Communication does not start and stop within the organization. External communication focuses on audiences outside of the organization. Examples of external communication include press releases about the organization, public relations information, advertisements about the organization’s product. Senior management—with the help of specialized departments such as public relations or legal—almost always controls communications that relate to the public image or may affect its financial situation. First-level and middle-level management generally handle operational business communications such as purchasing, hiring, and marketing. When communicating outside the organization (regardless of the level), it is important for employees to behave professionally and not to make commitments outside of their scope of authority. External communication also includes interactions between employees of the organization and it’s customers.

Communication Channels

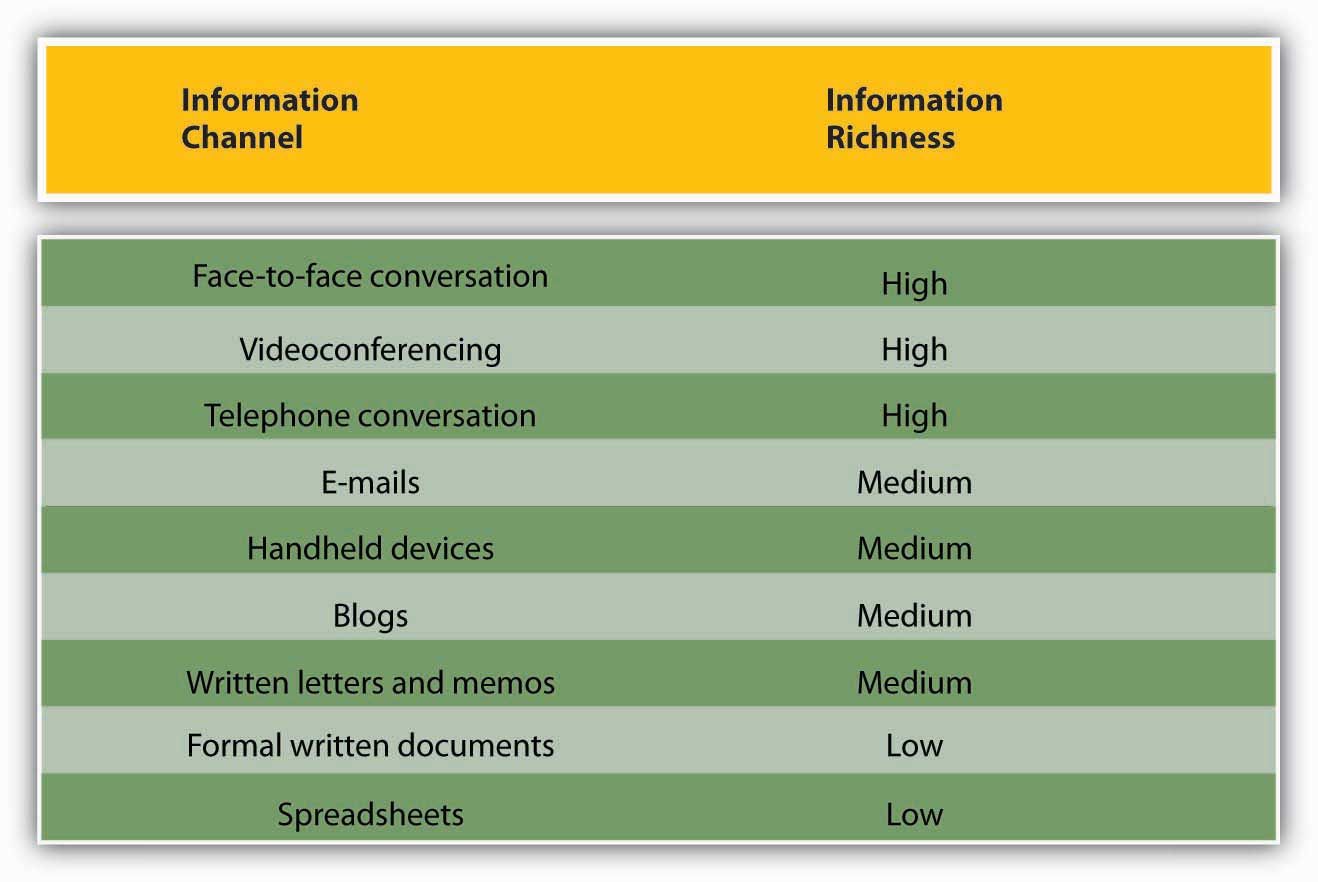

There’s a well-known expression that goes “It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.” It’s really both. A communication channel is the medium, mean, or method through which a message is sent to its intended receiver. Basic channels include written (hard copy print or digital formats), oral or spoken, and electronic/multimedia. These types of channels have varying channel “richness”.

Channel richness refers to the amount of nonverbal communication provided and the immediacy of feedback. Face-to-face communication is very high in richness because it includes nonverbal behaviors and has immediate feedback. A tweet is lower in richness because it allows only 140 characters to be transmitted (lack of nonverbal communication) with less immediate feedback.

I. Oral Channels

Oral channels depend on the spoken word. They are the richest mediums and include face-to-face, in-person presentations, mobile phone conferences, group presentations, telephone, video meetings, conferences, speeches, and lectures. These channels have lower message-distortion because nonverbal behaviors (including voice intonation) are included that provide meaning for the receiver. They also allow for immediate feedback of the communication to the sender. Oral channels are generally used in organizations when there is a high likelihood of the message creating anxiety, confusion, or an emotional response in the audience. For instance, a senior manager should address rumors about layoffs or downsizing in face-to-face meetings with management staff. This allows the receiver (audience) to get immediate clarification and explanations, even if the explanation is a simple but direct: “At this time, I just don’t know.”

Oral communications are also useful when the organization wants to introduce a key official or change a long-established policy, followed up with a written detailed explanation. Senior managers with high credibility usually deliver complex or disturbing messages. For example, a senior manager will usually announce plans to downsize in person so that everyone gets the same message at the same time. This will often include a schedule so people know when to expect more details.

II. Written Channels

Written communications include e-mails, texts, memos, letters, documents, reports, newsletters, spreadsheets, etc. (Even though e-mails are electronic, they are basically digital versions of written memos.) They are among the leaner business communications because the writer must provide enough context that the words are interpreted accurately. The receiver should be alert for ambiguity and ask for clarification if needed.

Written messages are effective in transmitting detailed messages. Humans are limited in the amount of data they can absorb at one time. Written information can be read over time. Reports can include supporting data and detailed explanations when it is important to persuade the receiver about a course of action. Written communications can be carefully crafted to say exactly what the sender means. Formal business communications, such as job offer letters, contracts and budgets, proposals and quotes, should always be written.

Because email is such a pervasive channel of communication, further discussion about this channel is warranted.

Use of E-Mail

The growth of e-mail has been spectacular, but it has also created challenges in managing information and an ever-increasing speed of doing business. Over 100 million adults in the United States use e-mail regularly (at least once a day). Internet users around the world send an estimated 60 billion e-mails every day, and many of those are spam or scam attempts. A 2005 study estimated that less than 1% of all written human communications even reached paper—and we can imagine that this percentage has gone down even further since then. To combat the overuse of e-mail, companies such as Intel have even instituted “no e-mail Fridays” where all communication is done via other communication channels. Learning to be more effective in your e-mail communications is an important skill.

An important, although often ignored, rule when communicating emotional information is that e-mail’s lack of richness can be your loss. E-mail is a medium-rich channel. It can convey facts quickly, but when it comes to emotion, e-mail’s flaws make it far less desirable a choice than oral communication—the 55% of nonverbal cues that make a conversation comprehensible to a listener are missing. E-mail readers don’t pick up on sarcasm and other tonal aspects of writing as much as the writer believes they will, researchers note in a recent study. The sender may believe she has included these emotional signifiers in her message. But, with words alone, those signifiers are not there. This gap between the form and content of e-mail inspired the rise of emoticons—symbols that offer clues to the emotional side of the words in each message. Generally speaking, however, emoticons are not considered professional in business communication.

You might feel uncomfortable conveying an emotionally laden message verbally, especially when the message contains unwanted news. Sending an e-mail to your staff that there will be no bonuses this year may seem easier than breaking the bad news face-to-face, but that doesn’t mean that e-mail is an effective or appropriate way to deliver this kind of news. When the message is emotional, the sender should use verbal communication. Indeed, a good rule of thumb is that the more emotionally laden messages require more thought in the choice of channel and how they are communicated.

Basic E-Mail Do’s and Don’ts

| DO | DON’T |

| …..use a subject line that summarizes your message & adjust it as the message changes

…..make your request in the first line of your e-mail. …..end your e-mail with your name and contact information. …..think of a work e-mail as a binding communication …..let others know if you’ve received an e-mail in error. |

…..put anything in an e-mail that you don’t want the world to see.

…..send or forward chain e-mails. …..write a Message in capital letters—this is the equivalent of SHOUTING. …..hit Send until you spell-check your e-mail. …..routinely “cc” everyone all the time. Reducing inbox clutter is a great way to increase communication. |

III. Electronic (Multimedia) Communications

Television broadcasts, web-based communications such as social media, interactive blogs, public and intranet company web pages, Facebook, and Twitter belong in this growing category of communication channels. Electronic communications allow messages to be sent instantaneously and globally. People can talk face-to-face across enormous distances. Marketing and advertising can be targeted to many different types of customers, and business units can easily communicate in real time. This is especially important when customers must be advised of product recalls or security issues.

Although extremely effective in sharing information with a large audience, the widespread utilization of electronic communications for business purposes can also be risky. In recent years, the private communications and customer files of many large corporations have been hacked and their data stolen. In 2016, New Jersey Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield was fined $1.1 million for failing to safeguard the personal information of medical patients. The company stored unencrypted sensitive data including birth dates and Social Security numbers on laptops that were stolen out of their main offices. Read the following blog on the use of social media in organizations: “The 5 Types of Social Media and Pros & Cons of Each.” by Pamela Bump. The Hubspot Marketing Blog.

Which Channel Is Best?

Quite simply, the best channel is the one that most effectively delivers the message so that it is understood as the sender intended. Nuanced or emotionally charged messages require a rich medium; simple, routine messages don’t need the personal touch. If you want to advise your department that at 2 p.m. you want to have a five-minute stand-up meeting in the hallway outside of your office to congratulate them on meeting a goal, then send a quick e-mail. You really don’t want people to reply with questions. E-mail is a lean medium but works very well when the content of the message is neither complex nor emotionally charged. On the other hand, a telephone call is a more appropriate channel to apologize for having to cancel a lunch date. The speaker can hear the sincerity in your voice and can express their disappointment or offer to reschedule. A good rule of thumb is the more emotional the context of the message, the richer the medium should be to deliver the message. But remember—even face-to-face business meetings can be followed up with a written note to ensure that both parties are truly on the same page.

Handheld devices, blogs, and written letters and memos offer medium-rich channels because they convey words and pictures/photos. Formal written documents, such as legal documents, and spreadsheets, such as the division’s budget, convey the least richness because the format is often rigid and standardized. As a result, nuance is lost. Below are some considerations when selecting the appropriate channel.

| Speed | Richness | Sender’s control over message creation | Sender’s awareness of receiver attention | Detailed Message | Permanency | |

| Face to Face | Synchronous | High | Low | High | Moderate | Low |

| Telephone | Synchronous | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Voicemail | Asynchronous | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Varies | Low | High | Low | High | High | |

| IM/Text | Varies | Low | High | Moderate/Low | Low | High |

| Printed Document (e.g., memo, policy manual) | Asynchronous | Low | High | Low | High | High |

| Social Media (E.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) | Varies | Varies | High | Moderate/Low | Varies | High |

Bottom line: There is not one best channel of communication to use in all situations. The key to effective communication is to match the communication channel with the goal of the communication.

Page Attribution

- Principles of Management. Lumen Learning.

- Management Principles. 2012.

OERs adapted for this reading include:

https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/management-principles-v1.1/s16-05-communication-channels.html