Chapter 6: Interpersonal Communication

6.4 Developing and Maintaining Romantic Relationships

Like other relationships in our lives, romantic relationships play an important role in fulfilling our needs for intimacy, social connection, and sexual relations. Like friendships, romantic relationships also follow general stages of creation and deterioration. Before we explore these stages, let’s look at our definition of romantic relationships.

In many Western cultures, romantic relationships are voluntary. We are free to decide whom to date and form life-long romantic relationships. In some Eastern cultures, these decisions may be made by parents, or elders in the community, based on what is good for the family or social group. Even in Western societies, not everyone holds the same amount of freedom and power to determine their relational partners. Parents or society may discourage interracial, interfaith, or inter-class relationships. While it is now legal for same-sex couples to marry, many same-sex couples still suffer political and social restrictions when making choices about marrying and having children. Much of the research on how romantic relationships develop is based on relationships in the West. In this context, romantic relationships can be viewed as voluntary relationships between individuals who have intentions that each person will be a significant part of their ongoing lives.

Think about your own romantic relationships for a moment. To whom are you attracted? Chances are they are people with whom you share common interests and encounter in your everyday routines such as going to school, work, or participation in hobbies or sports. In other words, self-identity, similarity, and proximity are three powerful influences when it comes to whom we select as romantic partners. We often select others that we deem appropriate for us as they fit our self-identity; heterosexuals pair up with other heterosexuals, lesbian women with other lesbian women, and so forth. Social class, religious preference, and ethnic or racial identity are also great influences as people are more likely to pair up with others of similar backgrounds. Logically speaking, it is difficult (although not impossible with the prevalence of social media and online dating services) to meet people outside of our immediate geographic area. In other words, if we do not have the opportunity to meet and interact with someone at least a little, how do we know if they are a person with whom we would like to explore a relationship? We cannot meet or maintain a long-term relationship without sharing some sense of proximity. We are certainly not suggesting that we only have romantic relationships with carbon copies of ourselves. It is more and more common to see a wide variety of people that make up married couples.

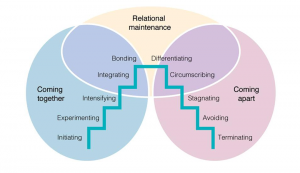

There are ten established stages of interaction that can help us understand how relationships come together and come apart (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). We will discuss each stage in more detail. We should keep the following things in mind about this model of relationship development: relational partners do not always go through the stages sequentially, some relationships do not experience all the stages, we do not always consciously move between stages, and coming together and coming apart are not inherently good or bad. Relationships are always changing—they are dynamic. Although this model has been applied most often to romantic relationships, most relationships follow a similar pattern that may be adapted to a particular context.

Knapp’s Stages of Relationship Development

Coming Together Phase

Stage 1: Initiating

In the initiating stage, we are attracted to someone, we may signal or invite them to interact with us. For example, you can do this by asking them to dinner, to dance at a club, or even, “I really liked that movie. What did you think?” The significance here is in the relational level (how the people feel about each other) rather than the content level (the topic) of the message. As the poet, Maya Angelou, explains, “Words mean more than what is set down on paper. It takes the human voice to infuse them with shades of deeper meaning.” The ‘shades of deeper meaning’ are the relational level messages that invite others to continue exploring a possible romantic relationship. Quite often, we strategize how we might go about inviting people into communication with us so we can explore potential romantic development.

Initiating is influenced by several factors:

- If you encounter a stranger, you may say, “Hi, my name’s Rich.”

- If you encounter a person you already know, you’ve already gone through this before, so you may just say, “What’s up?”

- Time constraints also affect initiation. A quick passing calls for a quick hello, while a scheduled meeting may entail a more formal start.

- If you already know the person, the length of time that’s passed since your last encounter will affect your initiation. For example, if you see a friend from high school while home for winter break, you may set aside a long block of time to catch up; however, if you see someone at work that you just spoke to ten minutes earlier, you may skip initiating communication.

- The setting also affects how we initiate conversations, as we communicate differently at a crowded bar than we do on an airplane.

- Culture can also impact the interaction. Some cultures have different expectations for interactions between people of different ages, sexes, or other situations while some cultures do not have as many expectations.

Even with all this variation, people typically follow their culture’s social scripts or interaction at this stage.

Stage 2: Experimenting

In the experimenting stage, we are getting to know the other person to identify compatibility beyond physical attraction. We share information about ourselves while looking for mutual interests, shared political or religious views, and similarities in family background. Common dating activities in this stage include going to parties or other publicly structured events, such as movies or a concert, that foster interaction and small talk. Small talk, a hallmark of the experimenting stage, is common among young adults just beginning to explore a new relationship by staying on polite, uncontroversial topics. Small talk can be annoying sometimes, especially if you feel like you have to do it out of politeness but it serves important functions, such as creating a communicative entry point that can lead people to uncover topics of conversation that go beyond the surface level, helping us audition someone to see if we’d like to talk to them further, and generally creating a sense of ease and community with others. If your attempts at information exchange with another person during the experimenting stage are met with silence or hesitation, you may interpret their lack of communication as a sign that you shouldn’t pursue future interaction. Even though small talk isn’t viewed as very substantive, the authors of this model of relationships point out that most of our relationships do not progress far beyond this point (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009).

Stage 3: Intensifying

In the intensifying stage, we continue to be attracted (mentally, emotionally, and physically) to one another, we begin engaging in intensifying communication. This is the happy stage (the “relationship high”) where we cannot bear to be away from the other person. It is here that you might plan all of your free time together, and begin to create a private relational culture. Going out to parties and socializing with friends takes a back seat to more private activities such as cooking dinner together at home or taking long walks on the beach. Self-disclosure continues to increase as each person has a strong desire to know and understand the other. In this stage, we tend to idealize one another in that we downplay faults (or don’t see them at all), seeing only the positive qualities of the other person.

Other signs of the intensifying stage can include:

- creation of nicknames or inside jokes

- increased use of we and our

- increased sharing emotionally (e.g., saying “I love you”.)

- increased physical intimacy

- increased communication about each other’s identities

- increased sharing of possessions and personal space (e.g., you have a key to your partner’s apartment)

How do you say I love you?

Putting Love to the Test

In his book The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate, Gary Chapman states that there are five ways people express and experience love: gift giving, quality time, words of affirmation, acts of service (devotion), and physical touch. He argues that although people can experience and appreciate each of the five styles, each person has a primary and a secondary love language.

Chapman has a quiz on his website that you can use to “discover your love language.” http://www.5lovelanguages.com/ In a column on WebMD, Stephanie Watson and her husband took the test and tried out each of Chapman’s languages http://www.webmd.com/sex-relationships/features/the-five-love-languages-tested#1

- What were your initial thoughts to how scholarly or helpful the love languages seemed?

2. Did you find this couple to be indicative of a real couple?

3. Why do you think Web MD would publish an article on the idea of love languages?

4. If you feel comfortable identify your love language and provide some examples of what you really need to fill your love tank.

Stage 4: Integrating

In the integrating stage, identities and personalities are merged, and a sense of interdependence (dependence on each other) develops. Verbal and nonverbal signals of the integrating stage are when the social networks of two people merge; those outside the relationship begin to refer to or treat the relationship partners as if they were one person (e.g., always referring to them together—“Let’s invite Olaf and Bettina”); or the relational partners present themselves as one unit (e.g., both signing and sending one holiday card or opening a joint bank account). Even as two people integrate, they likely maintain some sense of self by spending time with friends and family separately, which helps balance their needs for independence and connection. They are looking to measure how well their new partner fits into their lives and how other significant relationships (friends and family members) rate or respond to their new love interests.

When the “relational high” begins to wear off, couples begin to have a more realistic perspective of one another and the relationship as a whole. Here, people may recognize the faults of the other person that they so idealized in the previous stage. Also, couples must again make decisions about where to go with the relationship—do they stay together and work toward long-term goals, or define it as a short-term relationship? A couple may be deeply in love and also make the decision to break off the relationship for a multitude of reasons. Perhaps one person wants to join the Peace Corps after graduation and plans to travel the world, while the other wants to settle down in their hometown. Their individual needs and goals may not be compatible to sustain a long-term commitment.

Stage 5: Bonding

In the Bonding stage, a couple makes the decision to make the relationship a permanent part of their lives. In this stage, the participants assume they will be in each other’s lives forever and make joint decisions about the future. While marriage is an obvious sign of commitment it is not the only signifier of this stage. Some may mark their intention of staying together in a commitment ceremony, by registering as domestic partners, or by becoming Facebook official. Likewise, not all couples planning a future together legally marry. Some may lose economic benefits if they marry, such as the loss of Social Security for seniors or others may oppose the institution (and its inequality) of marriage.

Case In Point: Legal Marriage for Same-Sex Couples

The Netherlands became the first country (4/1/01), and Belgium the second (1/30/03), to offer legal marriage to same sex couples. Since then Canada (6/28/05) and Spain (6/29/05) have also removed their country’s ban on same-sex marriage. The state of Massachusetts (5/17/04) was the first U.S. state to do so and since then, many more states have followed. As of 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court granted the right marriage for both heterosexual and gay couples.

Domestic Partnerships

The status of domestic partner along with benefits for same-sex couples is recognized in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greenland, Iceland, The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and in the United States.

The Partners Task Force for Gay and Lesbian Couples has compiled a summary of marriage customs throughout history, as well as a list of governments that support same-sex marriage.

Not only do romantic couples progress through a series of stages of growth, they also experience stages of deterioration. Deterioration does not necessarily mean that a couple’s relationship will end. Instead, couples may move back and forth from deterioration stages to growth stages throughout the course of their relationship.

Coming Apart Phase

Stage 6: Differentiating

Individual differences can present a challenge at any given stage in the relational interaction model; however, in the differentiating stage, each partner in the relationship is reasserting their sense of self and trying to discover who they are as part of a couple. Communicating differences becomes a primary focus. Differentiating is the reverse of integrating, as we and our reverts back to I and my. People may try to re-establish some of their life prior to the integrating of the current relationship, including other relationships, hobbies, and interests, or possessions. For example, Carrie may reclaim friends who became “shared” as she got closer to her partner and their social networks merged by saying, “I’m having my friends over to the apartment and would like to have privacy for the evening.” Or, she may have liked playing golf on Sundays and abandoned it for Sunday dinners with her new partner and her new family. Now, she will want to return to what makes her happy. Individuals in the couple will want to have a sense of self that is independent and not necessarily tied to their partner.

Stage 7: Circumscribing

In the circumscribing stage, communication decreases and certain areas or subjects become restricted as individuals verbally close themselves off from each other. Circumscribe means to draw a line around something or put a boundary around it (Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2011). They may say things like “I don’t want to talk about that anymore” or “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.” If one person was more interested in differentiating in the previous stage, or the desire to end the relationship is one-sided, verbal expressions of commitment may go unechoed—for example, when one person’s statement, “I know we’ve had some problems lately, but I still like being with you,” is met with silence. Passive-aggressive behavior and the demand-withdrawal conflict pattern may occur more frequently at this stage. Couples often engage in more outward conflict.

Stage 8: Stagnating

During the stagnating stage, romantic partners begin to neglect the small details that have always bound them together and their relationship becomes routine. For example, they may stop cuddling on the couch when they rent a movie and instead sit in opposite chairs. Taken in isolation this example does not mean a relationship is in trouble. However, when intimacy continues to decrease, and the partners feel dissatisfied, this dissatisfaction can lead to worrying about the relationship. The partners may worry that they do not connect with one another in ways they used to, or that they no longer do fun things together. When this happens they may begin to imagine their life without the relationship. Rather than seeing the relationship as a given, the couple may begin to wonder what life would be like not being in the partnership.

They begin to assume that they know their partner and are dissatisfied with them. Instead of communicating, a person may think, “There’s no need to bring this up again because I know exactly how he’ll react!” Because of this kind of thinking, communication comes to a standstill.

This stage can be prolonged in some relationships. Parents and children who are estranged, couples who are separated and awaiting a divorce, or friends who want to end a relationship but don’t know how to do it may have extended periods of stagnation. Although most people don’t like to linger in this unpleasant stage, some try to avoid potential pain from termination, some hope to rekindle the spark that started the relationship, or even some enjoy leading their relational partner on.

Stage 9: Avoiding

The terminating stage of a relationship is when the relationship is ended. Termination can occur at any point in the relational development model or follow through the phases of coming together and coming apart. Termination can result from outside circumstances such as geographic separation or internal factors such as changing values or personalities that lead to a weakening of the bond. When terminating a relationship, people will often follow a pattern that is typical of their culture. In mainstream American culture, for example, it is typical for someone to start the formal termination of a relationship with a summary message that recaps the relationship and provides a reason for the termination (e.g., “We’ve had some ups and downs over our three years together, but I’m getting ready to go to college, and I either want to be with someone who is willing to support me, or I want to be free to explore who I am.”). The summary message may be followed by a distance message that further communicates the relational drift that has occurred (e.g., “We’ve really grown apart over the past year”), which may be followed by a disassociation message that prepares people to be apart by projecting what happens after the relationship ends (e.g., “I know you’ll do fine without me. You can use this time to explore your options and figure out if you want to go to college too, or not.”). Finally, there is often a message regarding the possibility for future communication in the relationship (e.g., “I think it would be best if we don’t see each other for the first few months, but text me if you want to.”). (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009)

Interpersonal Communication and You: Ending Romance

Often relationships end and do so for a variety of reasons. People may call it quits for serious issues such as unfaithfulness or long distance struggles. While sometimes people slowly grow apart and mutually decide to move on without each other. There are a plethora of reasons why people end their relationships. Sometimes it is not a pleasant experience: the initial realization that the relationship is going to cease to exist, the process of breaking up, and then the aftermath of the situation can be difficult to navigate. In an attempt to save you some potential heartache and arm you with advice/knowledge to pass along, here are some videos that propose some insight on dealing with such issues.

Moving Through the Steps of Relationships

You can probably recognize many of Knapp’s stages from your own relationships or from relationships you’ve observed. According to Knapp & Vangelisti (2009), movement through the steps of relationships is not linear or fixed. Although this is the sequence many people go through, each relationship is different and relationships may move forward or backward through the steps and may even skip steps. Some relationships move through the steps quickly while others move through them slowly. Some steps can be quicker than others. Some relationships will never progress beyond the initial steps and others will go a lifetime without terminating. A couple, for example, may enter counseling during the dyadic phase, work out their problems, and enter the second term of intensifying communication, revising, and so forth.It may also be noted that if we were to apply Knapp’s model to a different culture, we may see that they can also navigate through the stages of development. For example, in a collectivist culture in which they practice arranged marriages, the couple may enter at bonding but can begin at initiating after the ceremony to strengthen and maintain their relationship.

Obviously, simply committing is not enough to maintain a relationship through tough times that occur as couples grow and change. Like a ship set on a destination, a couple must learn to steer through rough waves as well as calm waters. A couple can accomplish this by learning to communicate through the good and the bad. Stabilization is maintaining a relationship by continuing to revise their communication and ways of interacting to reflect the changing needs of each person. Done well, life’s changes are more easily enjoyed when viewed as a natural part of the life cycle. The original patterns for managing dialectical tensions when a couple began dating, may not work when they are managing two careers, children, and a mortgage payment. Outside pressures such as children, professional duties, and financial responsibilities put added pressure on relationships that require attention and negotiation. If a couple neglects to practice effective communication with one another, coping with change becomes increasingly stressful and puts the relationship in jeopardy.

As the relationship is deteriorating, the couple can engage in relationship maintenance, a variety of behaviors used by partners in an effort to stay together. If the couple is differentiating or circumscribing, they may need to stabilize the relationship by talking about their problems and increasing intimacy behaviors. If they are in the stagnating or avoiding stages, they may need social support. As family members listen to problems or friends offer invitations to go out and keep busy, they provide social support. The couple needs social support from outside individuals in saving their relationships or going through the process of letting go and coming to terms with termination.In the deterioration stages, couples will maintain the relationship by communicating. They will discuss how to resolve problematic issues and may seek outside help such as a therapist to help them work through the reasons they are growing apart. This could also be the stage where couples begin initial discussions about how to divide up shared resources such as property, money, and responsibilities if they are leading to termination.

We often consider termination or “breaking up” as a negative or undesired effect of a poor relationship, but it can be a valuable experience that provides growth and may sometimes be a positive outcome. Imagine those that are able to leave a hostile or abusive relationship and return to healthy communication. Good or bad, people need to take the time to process the end of a relationship in order to fully understand the meaning of the relationship, why it ended, and what they can learn from the experience. Going through this is a healthy way to learn to navigate future relationships more successfully.

Understanding how relationships develop, coming together and apart, is valuable because we are provided with a way to recognize general communicative patterns and maintenance behaviors we have at each stage of our relationships. Knowing what our choices are, and their potential consequences give us greater tools to build the kind of relationships we desire in our personal lives.

Case In Point: Stressful Relationships Can Hurt You

Many things can cause us physical and mental harm. But, did you know that unhealthy relationships can too? Your life may be shortened by participating in a stressful relationship. According to researchers, stressful relationships can lead to premature death! As compared to relationships with infrequent worries or conflicts, stressful relationships can increase the chance of premature death by 50%! However, healthy, close bonds contribute to longevity. If you think you have a partner that drives you nuts, they may actually be killing you. This 2014 article in the New York Daily News describes a study that examined this phenomenon.